Having recently graduated from the UNC Chapel Hill School of Information and Library Science, I thought it would be fitting for my final blog post to examine a past graduation. In researching the class of 1966 for its 50th anniversary, I found that year’s commencement address. The speech, titled “Search for a Common Ground,” was given by Frank Porter Graham, the former President of UNC-Chapel Hill and the consolidated UNC system. Graham took the opportunity to address the Speaker Ban law that was then being challenged in court.

The law, officially titled “An Act to Regulate Visiting Speakers at State Supported Colleges and Universities,” was enacted by the North Carolina General Assembly in June of 1963. Although students and faculty across the state argued against the law, Chapel Hill was at the center of the protest. The most visible challenge to the law came in 1966 when two speakers were invited by UNC students to speak on campus. Because the speakers were members of the Communist Party, they had to address the students from the sidewalk of Franklin Street, across the wall from McCorkle Place. Graham’s commencement address was delivered just a few months after these speeches and the subsequent legal challenge that would lead to the law being overturned in 1968.

Graham opens his speech with a brief history of the University, from its founding in the 18th century through its closure during the Civil War to the administration of President Kemp Plummer Battle. Graham set this historical groundwork in order to present, “a balanced and fair analysis in seeking to find a common ground for our whole University family.” Graham is careful to present his thoughts in a neutral manner and not to embroil himself in the legal or political dispute. However, Graham does identify some of those opposed to the Ban including seven prominent student groups, the North Carolina Chapters of the American Association of University Professors in the Universities and Colleges of North Carolina, and the North Carolina Chapter of the Civil Liberties Union. With regard to the student body, he remarked that “in electing their present President, who I understand, made one of the main planks in his campaign for election the right of having student-sponsored, responsible, balanced and free open forums, were aware of his vigorous position on this matter and were sincere in their support of him.”

Graham also used this speech to address the charges of atheism and communism that were being leveled against the University and its representatives. In response to the fear of growing atheism, Graham reminds the audience of how

many honest young minds in the colleges have in times past effectively grappled with (1) the Copernican dethronement of the earth as the center of the universe, (2) the Darwinian evolutionary identification of man with animals, (3) the alleged overriding of spiritual power by Marxist economic determinism, (4) the Freudian subjection of the conscious mind to primitive drives and subconscious forces, and (5) the modification of absolute theories by the theory of relativity.

Similarly, he denies the claim that the University is soft on communism by stating,

the fact that the students wish to hear communists speak in their responsible and fairly balanced open forums along with speakers who represent the extreme right, the conservative and the liberal points of view, does not mean that they are soft on communism, but simply means they wish to understand the nature of the world of their generation.

While the Speaker Ban issue was resolved almost 50 years ago, speech on college campuses is still a divisive issue. Frank Porter Graham’s reconciliation of a state-imposed law with the values and mission of the University also parallels the controversy surrounding House Bill 2 in which North Carolina and the University are currently engaged.

For more information about the Speaker Ban Law, visit the A Right to Speak and Hear library exhibit or the exhibit in The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History

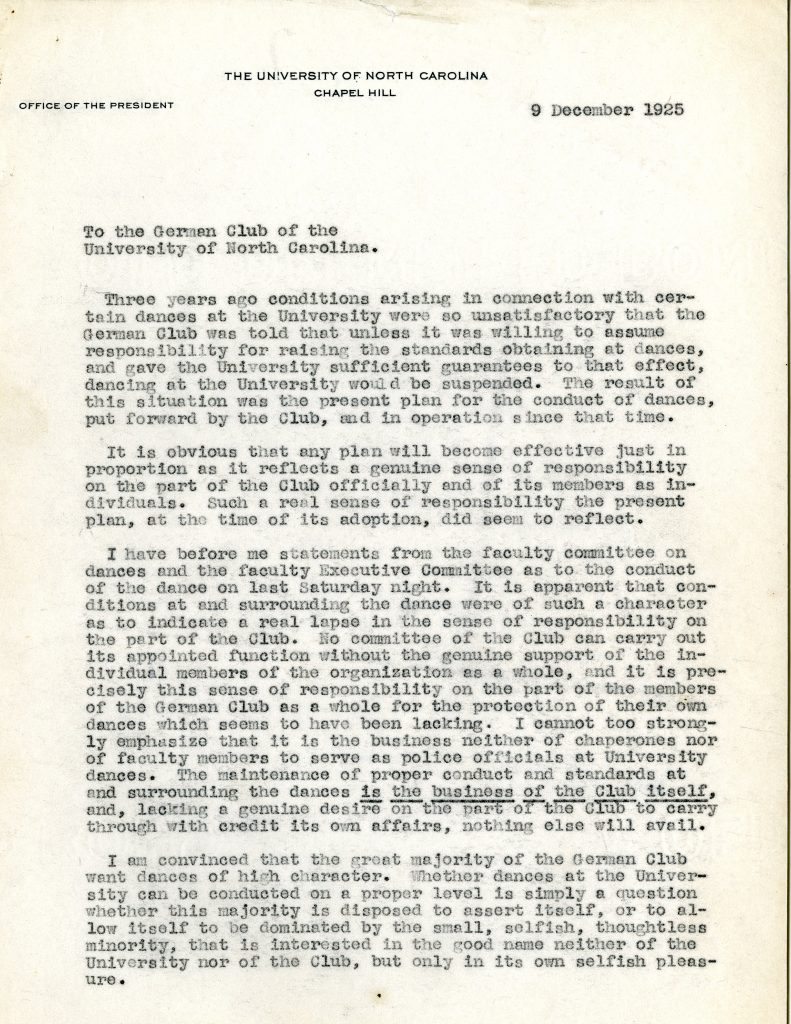

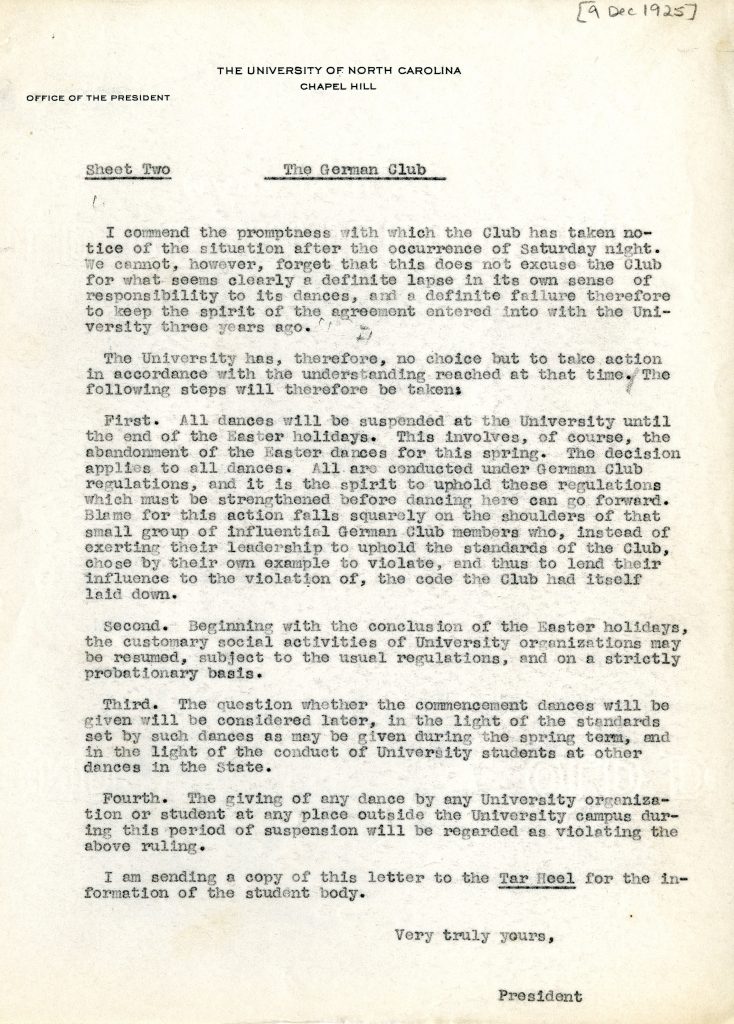

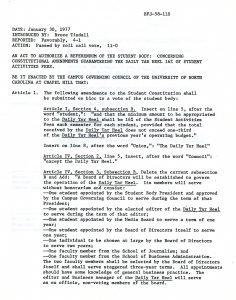

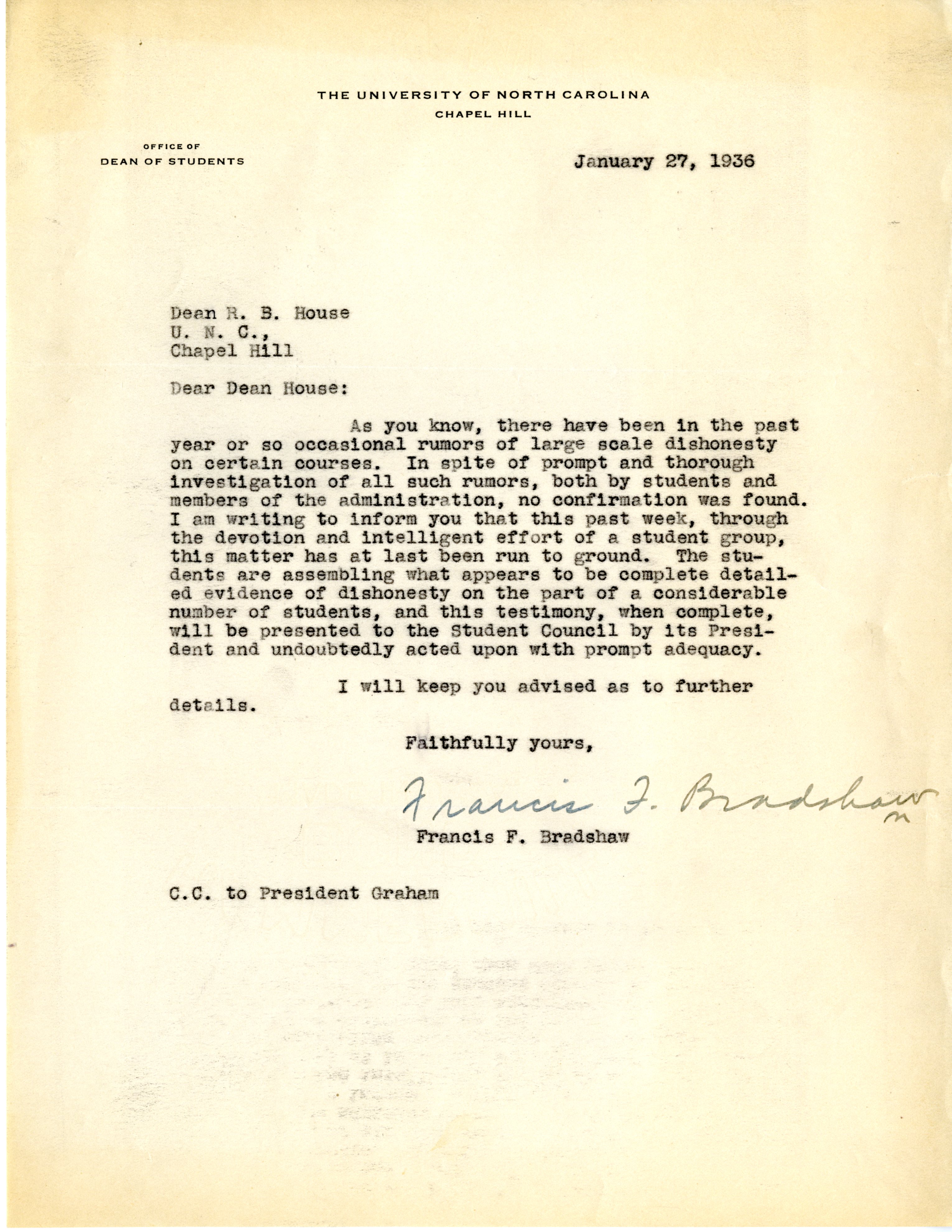

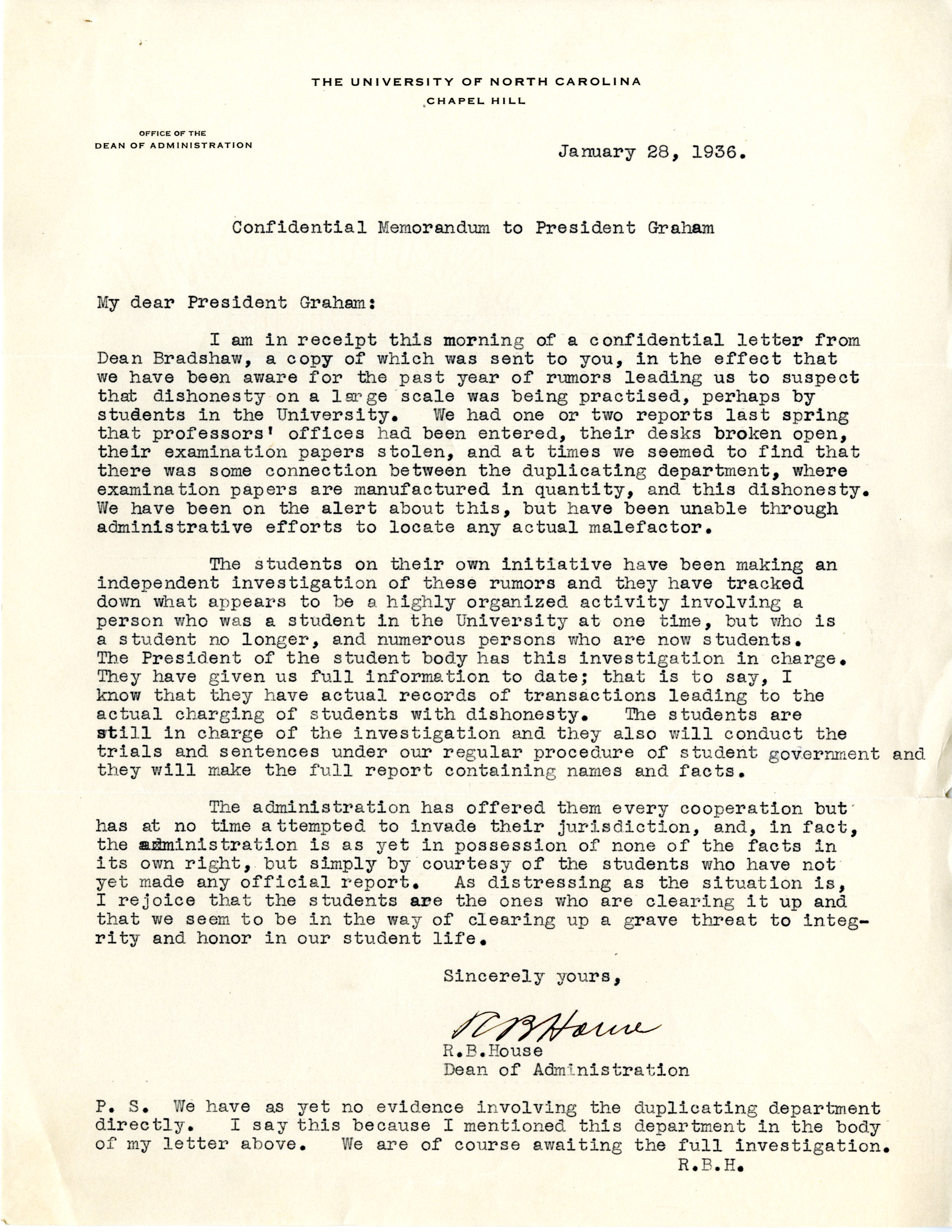

[Frank Porter Graham’s 1966 Commencement Address, from Office of Chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Joseph Carlyle Sitterson Records, 1966-1972 (#40022), University Archives]