Twenty years ago this week, UNC professor Michael Eric Dyson delivered the commencement address at the winter graduation ceremony. The speech, “Is America Still a Dream?,” was immediately controversial. Dyson, a faculty member in the department of communications, wrote about … Continue reading →

Twenty years ago this week, UNC professor Michael Eric Dyson delivered the commencement address at the winter graduation ceremony. The speech, “Is America Still a Dream?,” was immediately controversial.

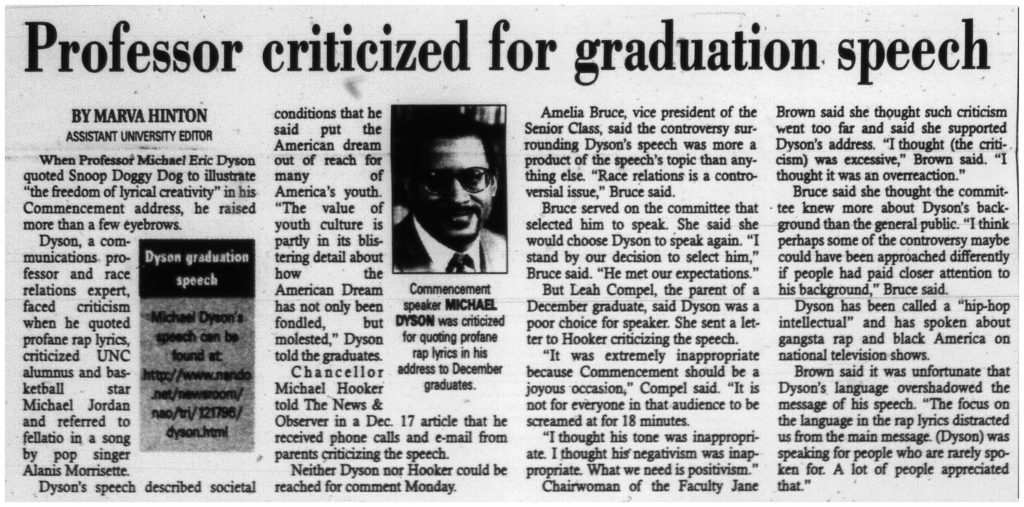

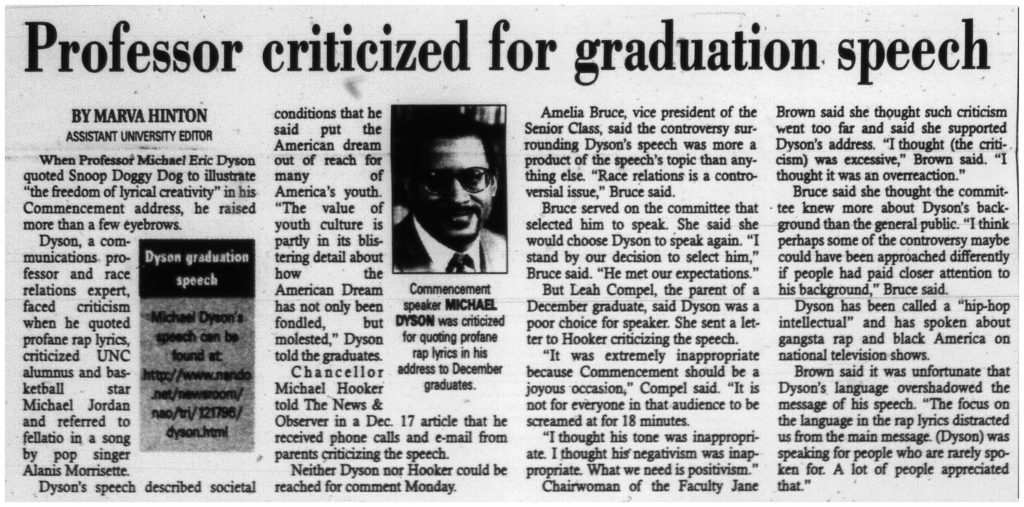

Daily Tar Heel, 7 January 1997.

Dyson, a faculty member in the department of communications, wrote about rap music and contemporary African American culture, topics he addressed in his commencement speech. Dyson spoke first about the idea of the American dream, saying, “The only hope for extending the American Dream is an acknowledgment that for many it has not been achieved.” He talked about the anger and frustration of many young people in the so-called “Generation X” and argued that youth culture in general, and rap music in particular, “sometimes conceals, at other times reveals, personal and social pain, the stark underside of the American Dream.”

Defending contemporary rap against its critics, Dyson said that in the work of many rappers “there is also a celebration of the freedom of lyrical creativity, rhetorical dexterity and racial signification.” He gave examples, quoting from the lyrics of Snoop Doggy Dogg and Notorious B.I.G., some of which included profanity.

Dyson encouraged the graduates to “get rid of the amnesia that clogs the arteries of American national memory” and to acknowledge that “the American Dream has been long in the making, and that your piece of it today as a college graduate, has come at great expense.” In his closing remarks, he commented on Michael Jordan’s recent gift to the UNC School of Social Work, and expressed disappointment that Jordan did not donate to support the new Black Cultural Center at Carolina.

Daily Tar Heel, 8 January 1997.

The use of occasional profanity, the criticism of Jordan, and the overall challenging tone of the speech were controversial. Apparently some students and parents walked out during the speech, but the larger outcry came later in local media and in letters from alumni to UNC Chancellor Michael Hooker. Several parents who attended the ceremony wrote to Hooker with complaints, as did many more alumni who read about it in local papers.

In his responses, Hooker was often apologetic, writing to one parent, “In my judgment, our speaker could have advanced his thesis without using offensive language, especially at a family-oriented ceremony such as graduation. Commencement is an occasion that calls for challenging, but also inspiring and uplifting comments.” A Daily Tar Heel editorial criticized Hooker, writing, “More than anything, he should have stood up for the truth behind Dyson’s comments. In sparking such controversy, he dared to present a harsh truth in place of sugar-coated platitudes.

Ultimately, the focus on the rap lyrics and the comments about Jordan overshadowed the larger content and message of Dyson’s speech. A Charlotte Observer editorial a few days later noted that his message was “not so radical,” continuing: “He was challenging graduates to understand our American history, the good and the bad in all its complexity.” In the Daily Tar Heel coverage of the controversy, Jane Brown, who was Chair of the Faculty, said, “The focus on the language in the rap lyrics distracted from the main message. (Dyson) was speaking for people who are rarely spoken for. A lot of people appreciated that.” The DTH editorial was even more direct: “Dyson, instead of facing criticism, should have received a standing ovation.”

Dyson left UNC in 1997 for a faculty position at Columbia University. He is currently on the faculty at Georgetown University and continues to write and speak about African American history and culture.

Sources and Further Reading:

Michael Eric Dyson: http://www.michaelericdyson.com/.

Charlotte Observer, 22 December 1996.

Daily Tar Heel, 7 January 1997 and 8 January 1997.

Independent Weekly, August 20-26, 1997.

Office of Chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: Michael Hooker Records, 1995-1999. Series 1, folder 29 (Commencement: General, January – March 1997). University Archives.

Office of President of the University of North Carolina (System): C. D. Spangler, Jr., Records, 1986-1997. Series 2.1, folder 809 (Commencement, December 15, 1996 – Mike Dyson Controversy). University Archives.