On this day, October 26, 2019, Carolina’s football Tar Heels will meet Duke for the 106th time, plus it is homecoming on the UNC campus. The winner will capture the Victory Bell.

Earlier this season, when Carolina beat Miami in Kenan Stadium with masterful play in the 4th quarter, the game became one of Kenan’s greatest wins…along with the ’48 Texas win, the ’57 Navy win, and the ’63 Georgia win (among others). One of those “others” was the 1978 Duke game—Coach Dick Crum’s first encounter with the Blue Devils from Durham. What transpired that afternoon is the stuff of legends, as Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard recalls.

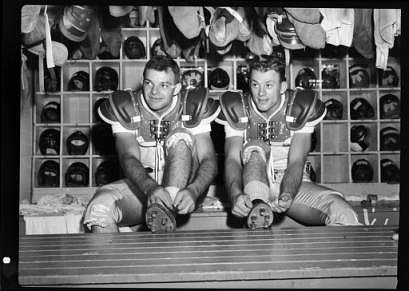

The 1978 UNC football season was head football coach Dick Crum’s first, which he would later call “a season of considerable adjustment.” The season got underway with a 14-10 win in Kenan Memorial Stadium against East Carolina. Then came three losses: Maryland, Pittsburgh, and Miami of Ohio. A win at Wake Forest on October 14 snapped the losing streak, but on October 21, rival NC State came into Chapel Hill and dominated the Heels, 34-7. Three road games followed: a win at South Carolina, followed by losses at Richmond and Clemson.

Hugh Morton joined a full house in “Death Valley” to witness a memorable game against Clemson on November 11. The Tigers were picked as an easy winner. After all, their record was 7-1 thus far in the season while Carolina was 3-6. But through the first three quarters, the Tar Heels led 9-6. Then with 9:43 on the clock in the fourth quarter, Clemson finally got its first touchdown of the game to take a 13-9 lead—a lead that lasted.

Two home games in Kenan followed the Clemson contest: Virginia on November 18 and Duke on the 25th. A 38-20 win against UVA set the stage for the famous 1978 game against Duke. Following the Virginia win, Coach Crum reminded his team about the importance of the Duke game. He offered a very special win-incentive, one that I choose to believe changed the outcome of the game. (More about that later.)

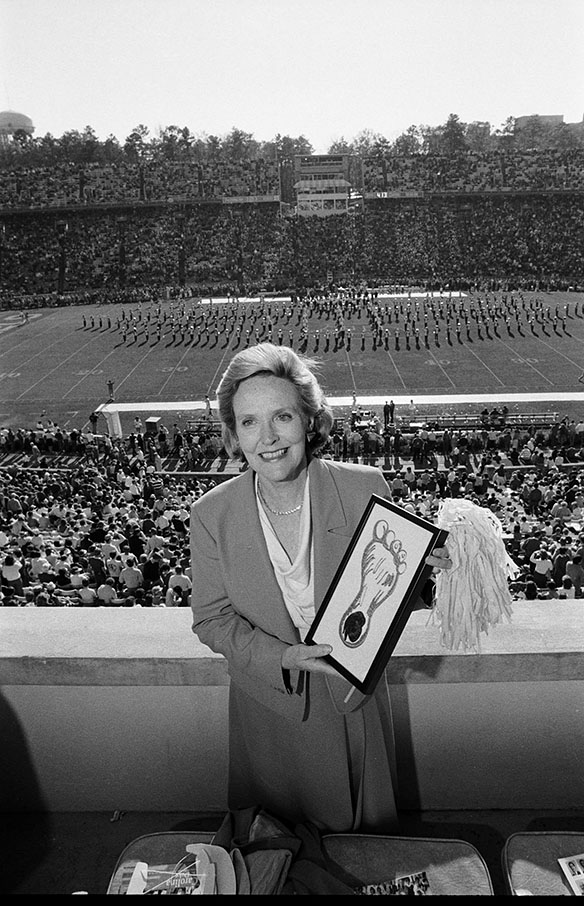

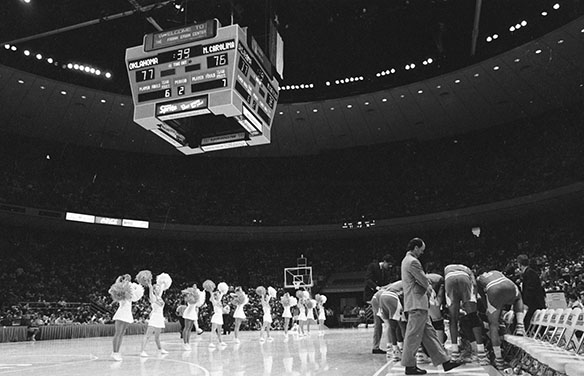

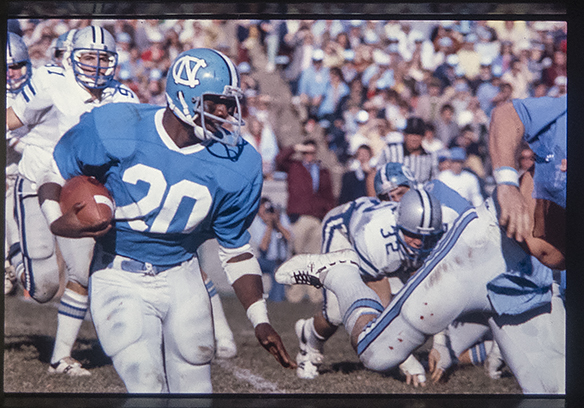

Saturday, November 25 was an average fall day with temperatures in the high 40s. At historic Kenan Memorial Stadium, 45,000 fans witnessed the 65th meeting between Carolina and Duke. On the sideline was photographer Hugh Morton in his usual position. Both teams had identical 4-6 records.

The first three quarters were ho-hum, with Duke dominating play. In the opening quarter, Carolina scored first with a Jeff Hayes field goal, then Duke followed at the 8:05 mark with a Scott McKinney field goal. McKinney added two more 3-pointers in the second quarter, and Duke led 9-3 at the half.

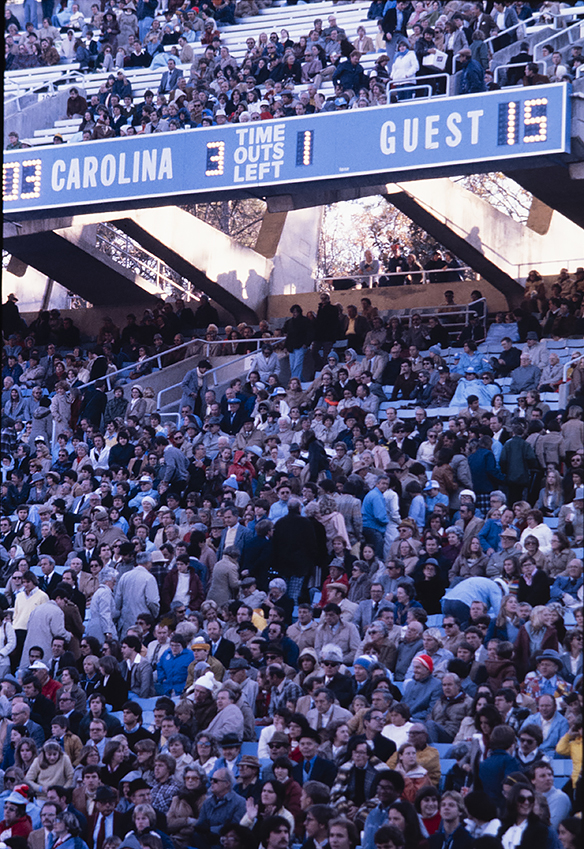

The third quarter was scoreless, as was most of the fourth, but with 4:20 remaining on the game clock, Duke quarterback Mike Dunn got loose on a keeper for a 29-yard touchdown. The two-point conversion attempt failed, but Duke was in control 15 to 3. At this point many of the fans wearing light blue chose to head home. Like Woody Durham use to say, “They must be giving something away in the parking lot.”

But Carolina wasn’t finished. Starting at the Tar Heel 23 yard line, quarterback Matt Kupec completed six of eight passes—covering the needed seventy-seven yards in ninety-six seconds. The final ten yards was a pass to end Bob Loomis. It was his seventh touchdown of the season, tying a record set by legendary Hall of Famer Art Weiner in 1949. Jeff Hayes converted the extra point, and cutting Duke’s lead to 15-10 with 2:46 remaining on the clock.

But Carolina wasn’t finished. Starting at the Tar Heel 23 yard line, quarterback Matt Kupec completed six of eight passes—covering the needed seventy-seven yards in ninety-six seconds. The final ten yards was a pass to end Bob Loomis. It was his seventh touchdown of the season, tying a record set by legendary Hall of Famer Art Weiner in 1949. Jeff Hayes converted the extra point, and cutting Duke’s lead to 15-10 with 2:46 remaining on the clock.

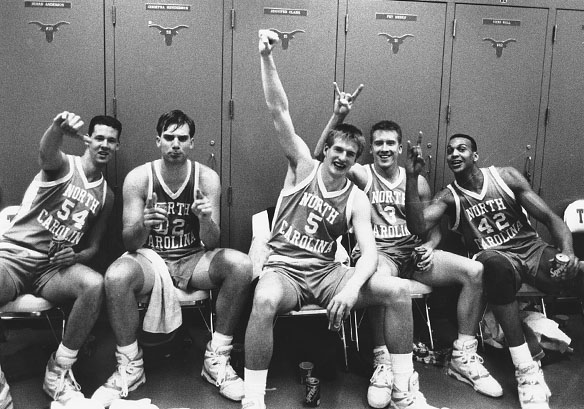

Carolina’s ensuing kickoff pinned Duke deep in their own territory. The Tar Heels defense held forth. They used their final two timeouts to stop the clock and forced Duke to punt. With 1:42 remaining and starting at the Carolina 39-yard-line, the Tar Heels were able to run ten plays during the next 89 seconds. During that 1:29, it was running back Amos Lawrence for 18 yards, then 4, then 21 more. With the ball at the Duke 18, Kupec passed to end Jim Rouse who stepped out of bounds at the Duke 11. At this point Duke lined up expecting another Kupec pass, but instead it was “Famous Amos” again who shook off tacklers and raced into the east end zone. Kupec’s pass for a 2-point conversion failed, but Carolina led 16-15 with the game clock at 13 seconds. During that final Tar Heel drive, Amos Lawrence was able to top the 1,000 yard mark for his second season in row. Following the scoring drive, the Carolina defense took over and preserved the win.

In his post game interview, Crum said, “That was simply one great football game.”

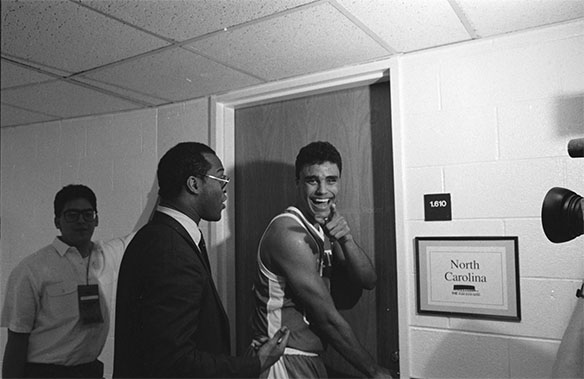

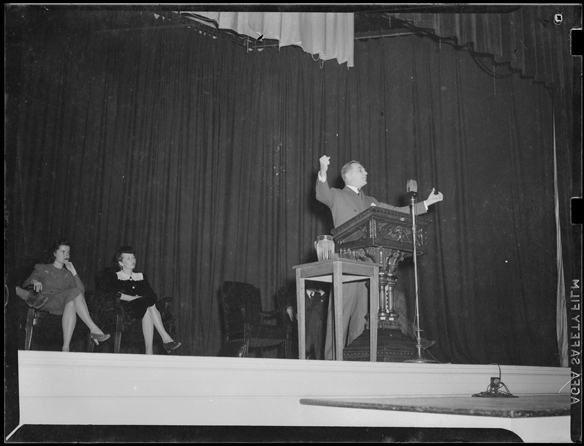

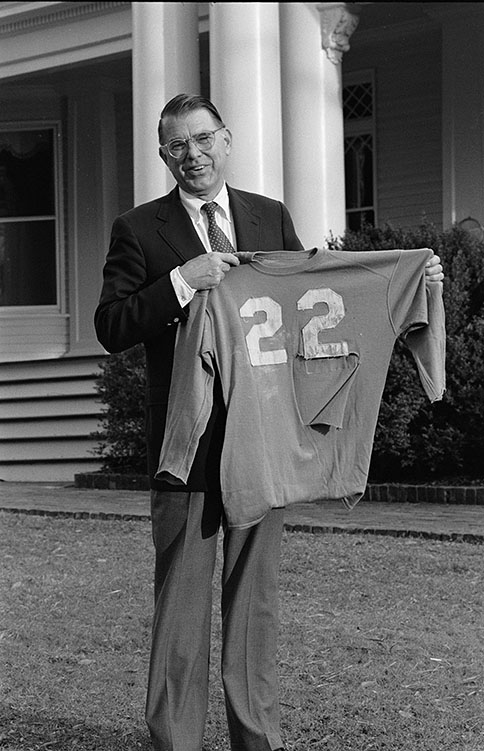

On Thursday, March 29, 1979, Crum made the 55-minute drive from Chapel Hill to Greensboro where he was the guest speaker at the Greensboro Kiwanis Club meeting. In addition to his speech notes, he also carried with him a very special piece of memorabilia.

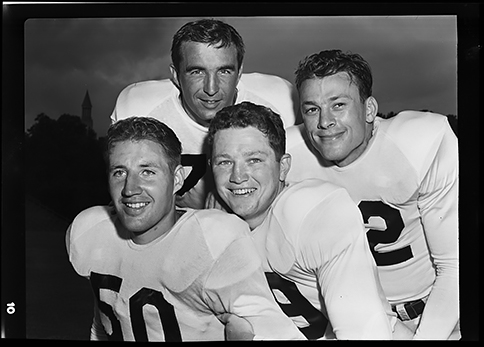

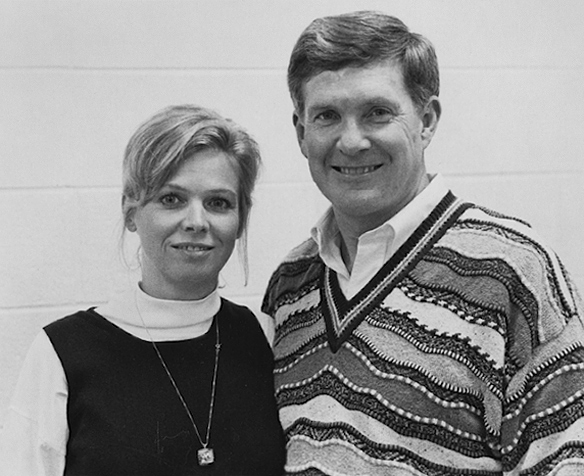

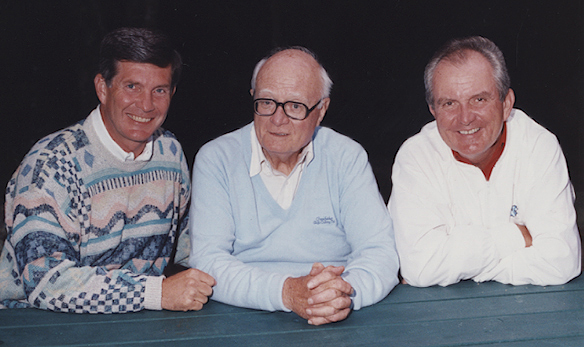

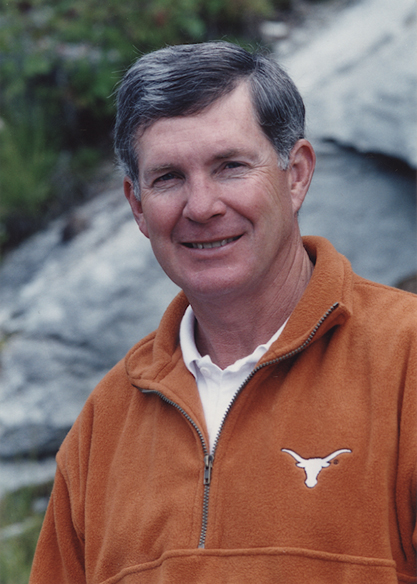

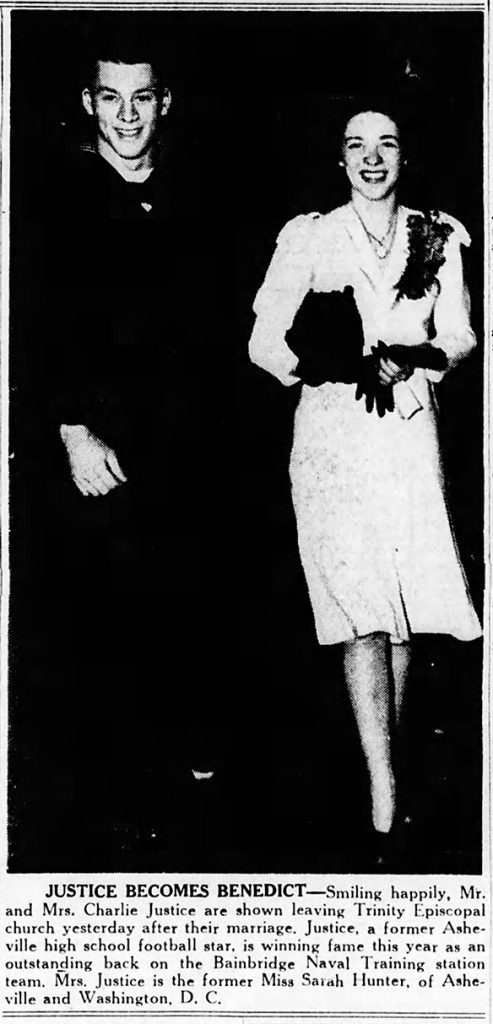

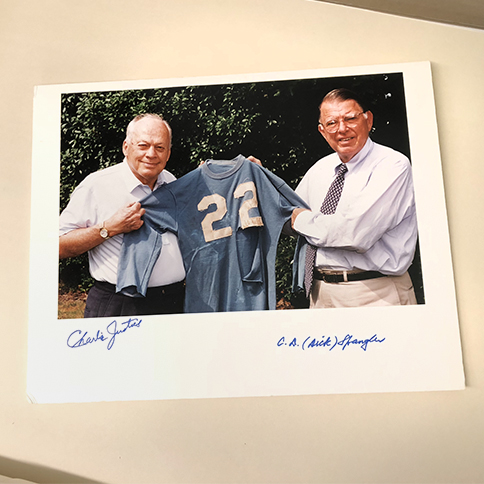

Spring football practice was underway in Chapel Hill, so the first part of Crum’s presentation was about those things that define spring practice…momentum, fundamentals, and recruiting. In the audience was a Kiwanian who was also a former UNC football player who understood all that spring practice stuff: Charlie Justice.

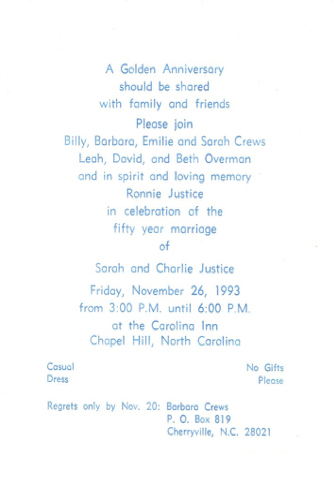

This day was Charlie’s first club meeting since his open heart surgery. Back on October 22, 1978, Justice was in Rockingham at North Carolina Motor Speedway where he was scheduled to be the Grand Marshall for the American 500 NASCAR race. But in the early morning hours he suffered chest pains and was transported to the local hospital. About three weeks later, on November 14, the legendary Tar Heel won his greatest victory: successful open heart surgery at Duke University Medical Center. He would later say, “that’s probably the best place for me to have serious surgery. . . You don’t think they would let me die on their watch, do you?”

At the Kiwanis meeting, after all was said about spring football practice and the upcoming UNC season, Crum took out a football that was signed by the 1978 UNC team members. “[In 1978], we had a season of considerable adjustment and needed a little incentive,” said Crum. “We had the Duke game coming up. If you’re not winning at Carolina you want to beat Duke to make things more peaceful in Chapel Hill for the winter. Charlie Justice was in the hospital . . . so after the Virginia game, I told the team if we beat Duke, we’d sign the ball and give it to Charlie.”

“To our players Charlie Justice is a legend.”

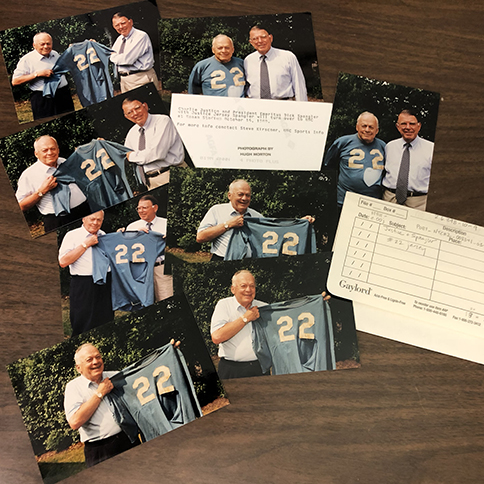

“You know what happened? With four minutes to go and trailing 15-3, I call the team in a huddle around me and tell them ‘we’ve got to win this one, remember, for Charlie Justice.'” Crum then called Justice to come forward and accept the game ball—the ball Famous Amos” Lawrence carried across the goal line for a victory over Duke from a ho-hum-game that became a Tar Heel thrill.