Today, February 23rd 2011, is the 66th anniversary of Joseph Rosenthal’s famous Pulitzer Prize winning photograph depicting Marines raising of the United States flag on Iwo Jima in 1945. That same day—1,500 miles to the southwest—also marked the last day of a major artillery barrage of the Intramuros, the 16th century walled fortress of the city of Manila.

Today, February 23rd 2011, is the 66th anniversary of Joseph Rosenthal’s famous Pulitzer Prize winning photograph depicting Marines raising of the United States flag on Iwo Jima in 1945. That same day—1,500 miles to the southwest—also marked the last day of a major artillery barrage of the Intramuros, the 16th century walled fortress of the city of Manila.

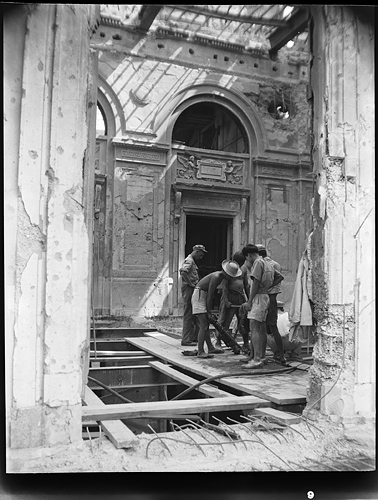

Fought between 3 February and 3 March 1945, the Battle of Manila ended three years of Japanese occupation. After February 23rd, United States forces engaged the Japanese in their remaining strongholds near the Intramuros, including the towering City Hall and the massively constructed Legislative Building. Hugh Morton, as a member of the 161st Signal Photographic Company, photographed both buildings sometime after the Japanese defeat.

The scenes above were not identified by Morton as being in Manila, but a bit of Googling and digging in other resources uncovered their location. It is likely that the images below are also from Manila, as the architecture is fitting with the descriptions of the buildings in that area of the city. Also, the frame numbers on the edge of the film—8 and 12—serve as possible bookends to frame number 9 on the image below. (Of course, they could be from separate rolls of film, so the numbers are not conclusive in and of themselves).

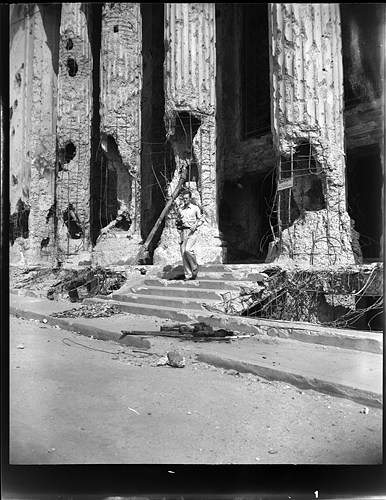

The image below (frame 1) shows Morton descending stairs in front heavily damaged columns.

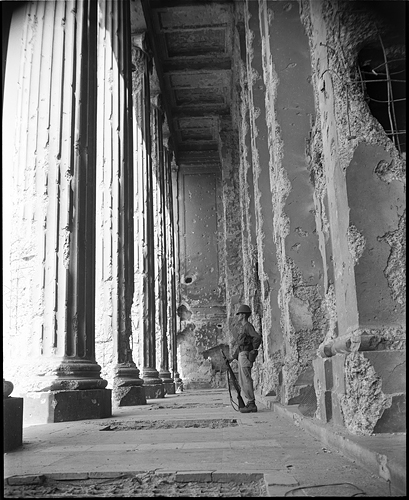

The location of the scene below of a soldier standing guard behind a colonnade (frame 4) is also unknown.

There’s several more photographs from Morton’s tour of duty in the Pacific islands; some remain unidentified, while others may be misidentified—such as a photograph of the “Pick-Up Cafe” building at 1437 Rizal Avenue that Morton had in an envelope labeled “Noumea, New Caledonia.” As far as Google Maps can tell me, there is no Rizal Avenue in Noumea, but there is a major street by that name in Manila.

There’s several more photographs from Morton’s tour of duty in the Pacific islands; some remain unidentified, while others may be misidentified—such as a photograph of the “Pick-Up Cafe” building at 1437 Rizal Avenue that Morton had in an envelope labeled “Noumea, New Caledonia.” As far as Google Maps can tell me, there is no Rizal Avenue in Noumea, but there is a major street by that name in Manila.

There are enough clues in the image that someone with some time and access to research tools such Manila city directories or census data (if not destroyed in the war!) might help resolve. So give them all a look . . . and if you try your hand at sleuthing and have some success, please share your findings with us in the comment section!

Skip to content

Processing the Hugh Morton Photographs and Films

I think that I remember Hugh saying that he was with one of the early troops to enter the old Walled City. He was “embedded” (word not used in that war) in/with (correct preposition?) the 25th Infantry. That might give you a clue. To me the most interesting thing about his account of entering the City was that our troops found what Hugh called “Japanese invasion money” in a safe in one of the buildings, printed in English and bearing the inscription “The Japanese Government garantees to pay the bearer….” The GIs scooped it up for souveniers but an officer who arrived made them hand it over to him.

As far as I know the 25th, at least Hugh, moved on down/up Phillippine Highway #1 from the City itself( Sorry I may be mixing my stories.)following the Japanese troops. Hugh was wounded before March 3rd. Some Japanese soldiers who had hidden in a cave overlooking the route had killed several of our men ( I remember Hugh included ‘a truck driver’ in his account)and a detail was dispatched to clean them out. Hugh went along to photograph the operation and so was right there when the Japanese blew up the hillside. He said he was “on 32 islands and wounded in 23 places or on 23 islands and wounded in 32 places.” A Morton exaggeration.

Julia, I’m wondering if Hugh was wounded later than you recalled. There is a photograph dated April 19, 1945 that is credited to “Morton” on the National Archives Website (http://www.archives.gov/research/military/ww2/photos/). See item number 152, “Veteran Artillery men of the `C’ Battery, 90th Field Artillery, lay down a murderous barrage on troublesome Jap artillery positions in Balete Pass, Luzon, P.I.” Morton, April 19, 1945. 111-SC-205918. (ww2_152.jpg).

It’s a terrific photograph!

Stephen, the April 19, 1945 date on the National Archives image does pose a question or two.

In the December 2, 1950 issue of “The State Magazine” (page 4), there is an article titled “Photo by Morton.” It is written by Bill Sharpe. He begins the piece with this:

“You’ve seen a lot of ‘Photos by Morton,’ but did you ever see how Hugh Morton takes a picture? How lovingly he handles his Speed Graphic camera, nestling it close to his shoulder? And well he might handle it lovingly, because his camera once saved his face; perhaps his life. It happened on Luzon, March 18, 1945…” Sharpe then goes on to recount the incident.

If the March date is correct, then the April date is questionable.

Then in an article from July, 1982, in “Carolina Lifestyle,” magazine, author Gary Govert has this:

“…in the hospital, a friend offered to read the badly injured Morton’s mail aloud to him. The first thing the two men opened was a letter from Morton’s mother. The letter said his father had died.”

So, when did Hugh’s father die? Then a little detective work to determine how quickly Morton got to a hospital after his injury, and how quickly mail from the United States got to Luzon. That could help determine the date.

There are two images in the online Morton Collection that show him in the hospital. The date given is March, 1945.

Later in the “Lifestyle” article (page 49) is this:

“Morton got home to Wilmington on emergency and convalescent leave in April (1945).”

So, if we can fill in a couple of blanks, we might be able to determine the date of Morton’s injury.

Hugh’s father died on March 1, 1945.If Bill Sharpe said Hugh was wounded on March 18th thren that is when he was wounded. Bill was somewhere between a s=best friend and a second father to Hugh.

Hugh was still in the hospital (Not the field hospital but the one, whatever it is called, they take you to after that.) when he learned of his father’s death. Mail to the troops moved much more slowly back then. He talked the powers that be into giving him a thirty day emergency furlough to go home. His furlough must have started June 1, because he went back to Fort Bragg to return to the Pacific on June 30th where he was discharged instead because of the just-created point system. ( A stroke of very good fortine.) I am sorry that I do not have a better grasp on the facts. but he did get back to the States in time to see some of his own film being shown in a theater here. When I get back to the mountains I will look for letters, etc. that may help if it is something you want to have in your files.

Julia’s comment prompts another question or two.

In October of 2003, Hugh Morton was a guest on UNC-TV’s “Biographical Conversations” and he described the events surrounding his being injured. (The bottom event on this link.)

http://www.unctv.org/biocon/hmorton/summers01.html

He said he had his Speed Graphic up to his eye when the blast shattered the camera lens. I wonder if he was able to get a shot before that? If so, where is that negative? I know many of Hugh’s wartime pictures are in places like the National Archives. Is there any way to search for those sources?

Again, Gary Govert, writing in the July, 1982 issue of “Carolina Lifestyle” magazine in an article titled “The Godfather of Grandfather,” (page 49) says this:

“Morton got home to Wilmington on emergency and convalescent leave in April (1945). A couple of days later he was walking past the downtown Royal Theatre when he noticed the marquee was advertising COMBAT SCENES OF PACIFIC WAR. Curious, he went inside and discovered that the Fox Movietone News was showing footage he had filmed the day he was wounded.”

So the next question would be, how long did it take for combat film to be processed, edited, and readied for showing in theaters in the United States?

While traveling over the weekend, I read about a third of the book Armed with Cameras: The American Military Photographers of World War II (1993) by Peter Maslowski. From what I’ve read so far, motion picture film was given the highest of priorities, but there were a lot of variables: 16mm versus 35mm, color (Kodachrome) versus black-and-white, available transportation, etc. Motion picture film was generally shipped far from the front because processing it was more complex. There were, however, field processing units. I’ll keep an eye out for more specifics as I continue reading.

A couple side notes regarding this thread:

Maslowski says that the Signal Corps committed 110 photographers to cover Luzon operations! Most went ashore on D-Day at Lingayen Gulf on January 9th; a couple websites on the 25th Division, however, state that they landed at San Fabian on Luzon on January 11th.

Maslowski also wrote, “As elsewhere during this war, the cameramen were inevitably ahead of or with the lead combat units. . . . In the Central Luzon Valley, several photo teams raced ‘not to keep up with, but to get ahead of, the assault troops so that they could photography the entry into Manila.'”

I believe I just correctly identified what was a misidentified photograph (based upon the negative being in an envelope Morton labeled “Noumea, New Caledonia”) that sheds a bit more light on this discussion. The photograph depicts a sign warning to soldiers that “bootleg liquor sold is poison.” [See https://dc.lib.unc.edu:82/u?/morton_highlights,6446%5D

The monument *behind* the sign looks to be the Andres Bonifacio Monument, which places the photograph in Caloocan City in Metro Manila, Philippines.

What is interesting about this photograph are the dates on the sign, the latest of which is March 24, 1945, indication that Morton was still in Manila in late March.

I am from Manila, Philippines. Glad to have dropped by here. That unknown neo-classical building you have with Greek-Roman columns is the Manila Central Post Office at the Liwasang Andres Bonifacio (Andres Bonifacio Square), designed by Filipino architect Juan Arellano and patterned after the original City Government Center buildings for Manila envisioned by Daniel Burnham. of Chicago at the turn of the 20th century when we became America’s colony. There are three other buildings in that neo-classical design which were destroyed in the Liberation of Manila in World War II. They were all rebuilt to their former glory including this one.