This Month in North Carolina History

On November 17, 1753, fifteen weary men and a wagon load of supplies arrived at a deserted cabin in the western part of North Carolina in what is today Forsyth County. The group had been six weeks on a journey from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Their task was to break ground in the wilderness for a new colony of their church, the Unitas Fratrum, better known as Moravians.

The roots of the Moravian faith ran back to the teachings of the Czech priest Jan Hus, whose attempts to reform the Roman Catholic Church led to his martyrdom in 1415. The church founded by Hus’s followers was destroyed or scattered in the Thirty Years War, and it was not until the 1720s that adherents of this religious tradition were offered refuge on the estate of Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf in Saxony. From their village of Herrnhut, the Moravians began sending missionaries around the world, including the colonial settlements of North America. To support their missionary effort, the Moravians founded towns in the American colonies, particularly in Pennsylvania. In 1753 Zinzendorf and other Moravian leaders accepted Lord Granville’s terms for the purchase of 100,000 acres of land from his vast holdings in North Carolina. An exploring party, led by Bishop August Gottlieb Spangenberg had already located a desirable tract of land, which they called Wachau, but soon came to be known as Wachovia.

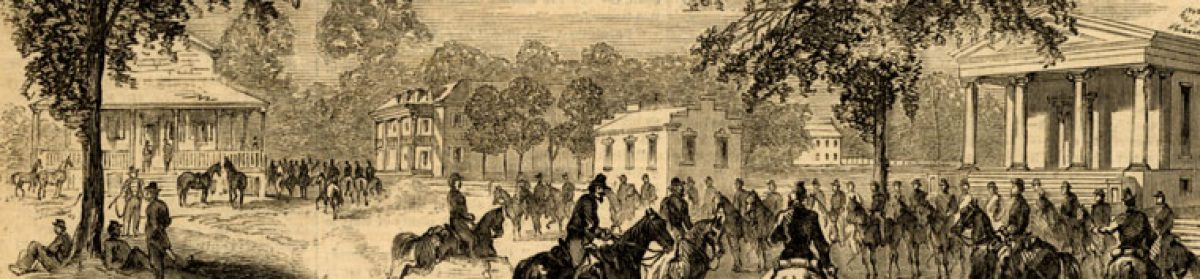

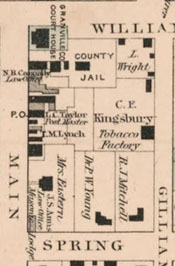

The advance party of fifteen founded the village of Bethabara, and soon Moravians from Pennsylvania added to the population. The Moravian pioneers were organized and industrious, carefully selected by church leaders for their skills and talents. Originally all of the settlers were drawn from the “single brethren,” but in 1755 married couples and children began arriving. The resulting overcrowding led to the founding of nearby Bethania in 1759. Finally, in 1765, the Moravians launched an ambitious plan to build a “city” in the wilderness. Located six miles from Bethabara, the new town of Salem quickly outgrew the older settlements to become the center of life in the Wachovia tract.

The Moravians brought to North Carolina their strong system of community life. In the original Wachovia settlements, property was held in common and settlers drew on community stores for food, tools, and other supplies. Towns were governed by the church, which had control or influence not only over municipal affairs, but also over many aspects of the personal lives of the people. The Moravians brought with them a love of music, which was an integral part of their religious life. Distinctive aspects of Moravian worship, such as the community meals called “love feasts,” continued in the North Carolina settlements. In time, church control withered and the strictures of communal life eased. More than most settlers in North Carolina, however, Moravians maintained the heritage of a distinctive way of life into modern times.

Sources:

Chester S. Davis. Hidden Seed and Harvest: A History of the Moravians. Winston-Salem, NC: Wachovia Historical Society, 1973.

Allen W. Schattschneider. Through Five Hundred Years: A Popular History of the Moravian Church. Bethlehem, PA: The Moravian Church in America, 1996.

Daniel C. Crews and Richard W. Starbuck. With Courage for the Future: The Story of the Moravian Church, Southern Province. Winston-Salem, NC: Moravian Church in America, Southern Province, 2002.

Image Source:

“Bethabara Church,” Board 8 (Area 7F) of Mary Grace Canfield Photographic Collection, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives.