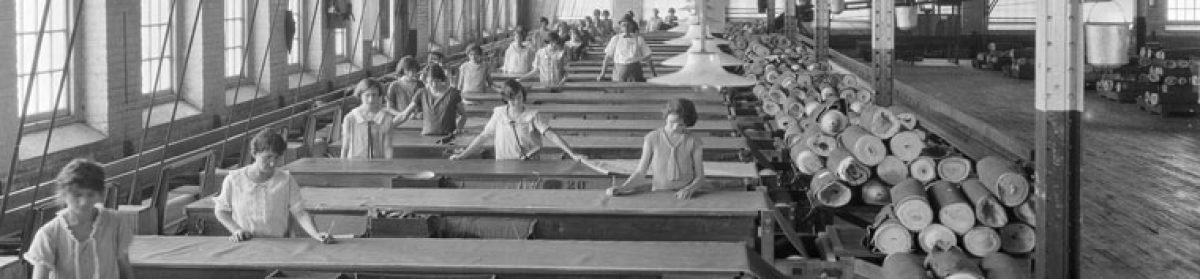

In the 1920s, North Carolina was ranked as the largest textile producer in the country, employing thousands, especially in the Piedmont. But as the Great Depression ushered in the 1930s, nearly one-quarter of all North Carolinians were out of work.

Textile workers who held onto their jobs faced long hours, low wages, and dangerous working conditions. Consequently, they joined unions and went on strike for livable wages and safe working conditions. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, mill employees across the state struck until their demands were met. For example, in 1921, at Cannon Mill locations in Charlotte, Concord, and Kannapolis, an estimated 9,000–11,000 people went on an 8-week strike.

Using Chronicling America, we can research these strikes and find out more about the history of organized labor in North Carolina.

Readers can see the same reasons behind the strikes. Many mention wage reductions, especially impactful during the years of the Great Depression. Sometimes these wage cuts were documented to be as high as 25%.

Over a dozen strikes occurred in the state between 1931 and 1933, many related to how much employees were being paid. In December 1931, a small strike at the Klumac Cotton mill in Salisbury was called. In July 1932, 6,000 struck in High Point for three weeks, and in August, roughly 500 at mills in Rowan County walked out, all in response to wage reductions.

One of the other common reasons for strikes was because of “stretch-out.” Officially called “scientific management,” it was a time management system that was designed to save companies money by making workers more efficient, leading them to do more in less time.

However, mill workers saw it as a way to cut jobs and have fewer people do more work without an accompanying rise in pay. Mill workers called it “stretch-out” as they felt they were stretched to their limits. In August 1932, over 1,000 workers in Rockingham and Spindale walked out, demanding an end to “stretch-out,” and restoration of their wages to pre-cut pay levels.

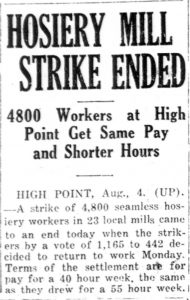

Textile workers struck for other reasons as well. Hosiery mill workers in High Point demanded the same pay for a 40 hour week that they previously received for a 55 hour week. One Spindale strike petitioned for the removal of a specific superintendent. Mill strikes persisted well into the 1930s, with hundreds or thousands of workers often stopping work for weeks on end.

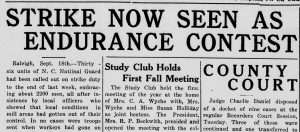

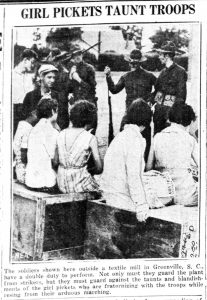

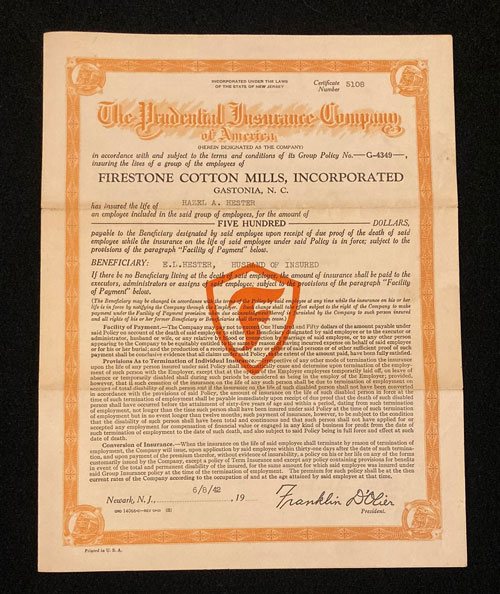

Most strikes were nonviolent, although there were exceptions. The most infamous strike occurred in Gastonia in June 1929 where violence broke out and strike organizers were killed. In February 1932, a strike of 500 cotton mill workers in Bladenboro ended after three officers were shot, although “[n]o one was wounded seriously.” One fearful 1937 editorial wrote that striking inevitably meant violence and death – “Bloodshed follows a Southern textile strike almost as inevitably as night follows day.”

State and national governments often intervened in settling or ending strikes. In 1921, National Guard troops were ordered to Concord to “take complete charge of the textile strike situation,” which only broke after a visit by Governor Cameron Morrison. In 1929, it cost the state over $27,000 and $12,000 to again put National Guardsmen on duty during textile strikes in Marion and Gastonia, respectively.

Morrison was not the only governor to involve himself – in 1932, Governor O. Max Gardner persuaded 5,000 strikers in High Point to submit to arbitration. The following year, the State Department of Labor stepped in to settle strikes in Concord and in Forest City.

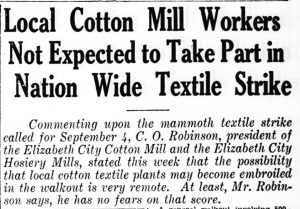

A strike’s success was not always guaranteed – neither was positive reception. In 1934, mill workers in Mecklenburg County were “hot” for a strike, but those in Rutherford County, Gaston County, Marion, and High Point all responded negatively. One editorial in The Independent (Elizabeth City) asked why people across the state were striking, and if the cause was “hunger, communism or a general state of dissatisfaction…”

In 1933, President Roosevelt signed the National Industrial Recovery Act, which set minimum wages for textile workers in the South – about $12 a week. In September 1934, a massive national strike was held, but many textile workers felt that because of a lack of union support, membership was not important, and union numbers in North Carolina never recovered.