This Month in North Carolina History

George Washington Vanderbilt’s vision of a country house in the mount ains of western North Carolina produced Biltmore, the magnificent mansion near Asheville that has become one of the best known tourist attractions in North Carolina. Vanderbilt also planned an estate worthy of the house, ultimately buying more than 120,000 acres of mountain land. He had hired one of the country’s premier landscape architects to lay out the lands and gardens surrounding Biltmore, and, in the same spirit, Vanderbilt wanted his vast forest lands managed by a skilled, professional forester. At the time there were only two trained foresters in the United States, Gifford Pinchot and Bernard Eduard Fernow. Pinchot had prepared preliminary plans for the Biltmore forests but would not take on the permanent job of caring for them. On the recommendation of Pinchot and others, Vanderbilt sought his forester in Europe, offering the position to Carl Alwin Schenck, a native of Darmstadt, Germany, who studied forestry at the Universities of Tubingen and Gissen, receiving his Ph. D. in 1894.

ains of western North Carolina produced Biltmore, the magnificent mansion near Asheville that has become one of the best known tourist attractions in North Carolina. Vanderbilt also planned an estate worthy of the house, ultimately buying more than 120,000 acres of mountain land. He had hired one of the country’s premier landscape architects to lay out the lands and gardens surrounding Biltmore, and, in the same spirit, Vanderbilt wanted his vast forest lands managed by a skilled, professional forester. At the time there were only two trained foresters in the United States, Gifford Pinchot and Bernard Eduard Fernow. Pinchot had prepared preliminary plans for the Biltmore forests but would not take on the permanent job of caring for them. On the recommendation of Pinchot and others, Vanderbilt sought his forester in Europe, offering the position to Carl Alwin Schenck, a native of Darmstadt, Germany, who studied forestry at the Universities of Tubingen and Gissen, receiving his Ph. D. in 1894.

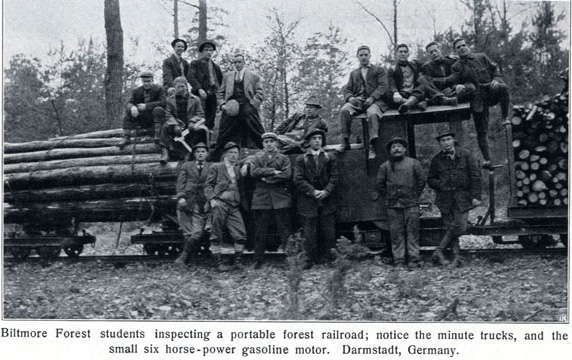

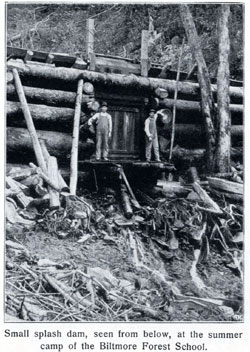

Schenck came to the United States in 1895 and threw himself into the work of organizing and managing the vast forest lands of Biltmore. Schenck supervised a team of rangers and laborers patrolling the forests, cutting trees, building roads, and planting seedlings. Almost from the beginning, however, Schenck also had the help of volunteers, boys from local families who asked to be his “apprentices” to learn scientific forestry. As they traveled by horseback over the mountainous terrain visiting work sites, Schenck explained to the boys what he was doing and why. The number of young men wanting to learn from Schenck steadily increased and led him to formalize the educational process. In September 1898, the Biltmore Forest School opened in abandoned farm buildings on the estate, becoming the first school of forestry in the United States.

Schenck believed in a hands-on approach to the study of forestry. Lectures in the morning by Schenck or visiting experts were followed by afternoons in the forest directly applying what was being taught. Schenck was a firm disciplinarian—he was a reserve officer in the Imperial German Army—whom the boys called “the man who looks like the Kaiser” because of his military bearing and his upturned handlebar moustache. Striding energetically around his classroom or a forest clearing speaking enthusiastically in his strong German accent and followed by his faithful dachshund, Schenck was a figure that his students remembered all their lives with respect and affection.

The pioneering Biltmore Forest School was short-lived, graduating its last students in 1913 when Schenck returned to Europe. By the time it closed, however, schools of forestry had appeared at several American universities and graduates of Biltmore had moved into positions of leadership in government forestry, private forestry, and forestry education throughout the United States.

Sources

Carl Alwin Schenck. The Birth of Forestry in America: Biltmore Forest School, 1898-1913. Santa Cruz, CA: Forest History Society, 1974, c. 1955.

Forestry Comes to America. Washington, DC: U. S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forestry Service, 1971.

“Biltmore Forest School.” Encyclopedia of North Carolina. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2006.

Image Source:

Carl Alwin Schenck. Logging and lumbering; or, Forest utilization. A textbook for forest schools. [Darmstadt, Printed by L.C. Wittich, 1912?]. NC Collection Call Number: C634.9 S32L [splash dam: p. 28; Biltmore Forest students: p. 55.]