If you were to examine a UNC yearbook, you would encounter the expected contents: sports pages, page after page of fraternities, and reminders of the year’s major events. However, there are more mysterious things lurking in those pages courtesy of the Order of Gimghoul: coded messages.

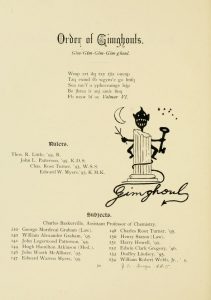

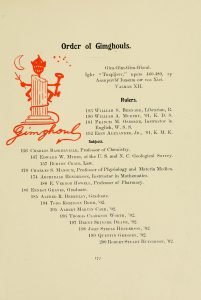

A bit of background knowledge is needed to understand any of this in the first place. The Order of Gimghoul, a males-only secret society, was founded in 1889 by Edward Wray Martin, William W. Davies, Shepard Bryan, Andrew Henry Patterson, and Robert Worth Bingham, all students at UNC-Chapel Hill. The legend of Peter Dromgoole was used as the basis for their society and it was founded as the Order of Dromgoole. The name was later changed to Gimghoul “in accord with midnight and graves and weirdness.” Martin created the initiation ritual, constitution, and bylaws, and as years passed they evolved. The order consolidated its beliefs and customs into a combination of the Dromgoole legend and the ideals of Arthurian chivalry.

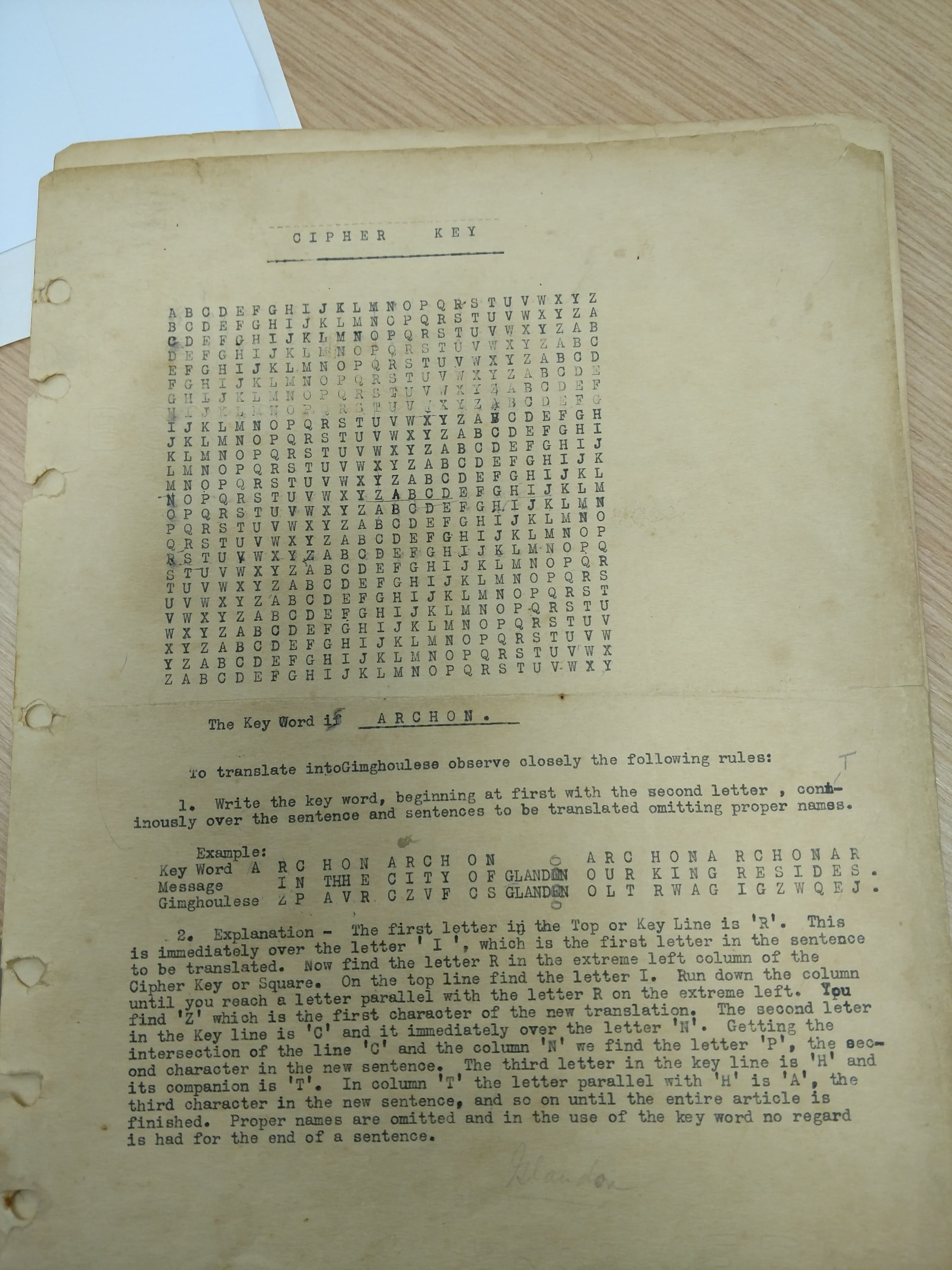

Despite being secret, the Order frequently has a yearbook page. The first Gimghoul page appeared in The Hellenian in 1890. Since the Order’s creation, the Rex—the term for the Gimghoul leader—has been expected to write a coded message in the yearbook each year, and a message has appeared in almost every yearbook produced since 1892. The Hellenian yearbook was replaced by The Yackety Yack in 1901, but the messages continued. On occasion, a message from a preceding year will be repeated.

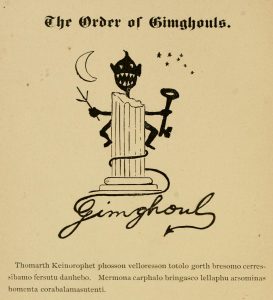

The messages are almost always accompanied by the Gimghoul emblem, a ghoul that grins wickedly and spells out “Gimghoul” with his tail. In his left hand he holds the Mystic Key, in his right the Cross of Gimghoul. Each emblem also includes the moon, a group of 7 stars, and a column set on a triple foundation.

A selection of the decoded messages are presented in their entirety below.

1895: “Now let us all take caeer [cheer] and eook [look] to wxat’s [what’s] to come for tas’s a prospaeons [prosperous] year in whiya [which] we ael aape [all hope] wox to moy it be.”

The writer of the 1895 message made a minor alteration to the key used to code “Gimghoulese,” but even with this taken into account the message is garbled. The writer made mistakes in his use of the alphabet square, making it difficult to decipher. In addition, it was evidently handwritten: the typesetter misunderstood several letters.

1896: “On being tied to a tree in the initiatiop [initiation], Butlxr [Butler] desertbd [deserted] He was chughk [caught] in bed and initiated nevertheless. The Devil is hard to beat.

Yours–Valmar VIII”

The Butler mentioned here was a math instructor initiated in 1895-6. The process was a complicated one: neophytes would gather in Room 22 of South Building around midnight, awaiting their fate. Eventually, a robed and hooded figure would arrive and lead inductees eastward, on a path through Battle Park. A secondary, harsher path to Piney Prospect would be used to reach the final initiation point, Dromgoole Rock. There would stand the Rex himself, who would finally declare one a member.

The mysterious author, Valmar VIII, was the Rex William R. Webb. A Valmar is credited as authoring most messages.

1899: “In this, the tenth year, let every loyal knight renew his love for Gimghoul, and aid in continuing its noble work. Valmar X”

1901: “Read ‘Guinevere’ lines 460-480, in Tennyson’s Idylls of the King. Valmar XI”

The lines referred to read as follows:

In that fair Order of my Table Round,

A glorious company, the flower of men,

To serve as model for the mighty world,

And be the fair beginning of a time.

I made them lay their hands in mine and swear

To reverence the King, as if he were

Their conscience, and their conscience as their King,

To break the heathen and uphold the Christ,

To ride abroad redressing human wrongs,

To speak no slander, no, nor listen to it,

To honour his own word as if his God’s,

To lead sweet lives in purest chastity,

To love one maiden only, cleave to her,

And worship her by years of noble deeds,

Until they won her; for indeed I knew

Of no more subtle master under heaven

Than is the maiden passion for a maid,

Not only to keep down the base in man,

But teach high thought, and amiable words

And courtliness, and the desire of fame,

And love of truth, and all that makes a man.

1902: “We saould not pass from the iarth uithknr trcces to corry oqd memonh xvb postesity.”

This message is supposed to read “we should not pass from the earth without leaving traces to carry our memory to posterity.”

1903: “The wise leader is he who knows when to follow.”

1904: “The great works in this world spring from the ruins of greater projects.”

1911-1914: “Sir Knights, remember noblisse oblige and be courageous, be loyal, be true. Valmar XXII”

1915, 1918, 1919: “To all Sir Knights the world around, greetings from Hippol Castle, Glanden.”

1921: “To Sir Knights the world over — greetings!”

1922, 1923: “Never let nothing get you down.”

1924: “Fight to the finish and never say die.”

1925: “One thing is forever good; that one thing is success.”

1930: “Courage, loyalty, truth, love: these four badges, Sir Knights, you must ever wear.”

1935: “The power to meet life with love and courage is all that makes life worth living.”

1944-1946: “Speed to all ye Sir Knights of the Order who have entered the service of our great country.”

Due to the secret nature of the Order, Gimghoul records in Wilson Library that are less than 50 years old are closed to everyone but members of the Order and those with written permission from the current Rex. However, records older than 50 years (including the materials referenced here) are open for research in Wilson Library.

References:

“Papers (Open), 1832-1996” in the Order of Gimghoul of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Records, 1832-2009 #40262, University Archives, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The Hellenian and Yackety Yack yearbooks, North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (View online via DigitalNC)

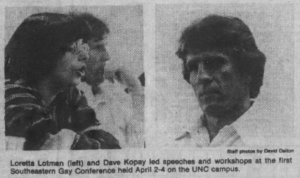

The three spokespeople in question were Dave Kopay, Loretta Lotman, and Perry Deane Young. Dave Kopay was a running back for the Washington Redskins and one of the first professional football players to come out as gay (in December 1975).

The three spokespeople in question were Dave Kopay, Loretta Lotman, and Perry Deane Young. Dave Kopay was a running back for the Washington Redskins and one of the first professional football players to come out as gay (in December 1975).