Forty-four years ago today, five leaders of the Communist Workers Party (CWP) were shot and killed at a demonstration in Greensboro, N.C., by members of the Ku Klux Klan and the American Nazi Party. The violence of the “Greensboro Massacre” lasted only eighty-eight seconds, but ended with the murders of CWP organizers Sandra Smith, James Waller, William Sampson, César Cauce, and Michael Nathan.

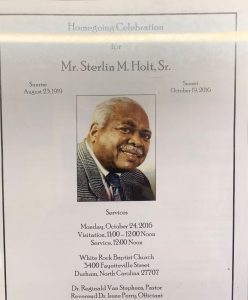

Since the massacre, families and friends of the people murdered have tried to keep the memories of their loved ones alive through commemorations, such as the 2015 placement of a North Carolina Highway Historical Marker at the site of the shootings. In 1980, families and survivors established the Greensboro Justice Fund (later the Greensboro Civil Rights Fund, or GCRF) to fundraise and organize for a civil suit on behalf of the victims. That lawsuit, Waller v. Butkovich, resulted in a jury finding two Greensboro police officers and six Klansmen and Nazis liable for the wrongful death of the deceased and a judgment of close to $400,000 in damages to the plaintiffs.

In 1992, the Southern Historical Collection acquired the Greensboro Civil Rights Fund’s immense archive of records relating to the massacre and subsequent legal cases. The library also preserves the papers of massacre survivors John Kenyon “Yonni” Chapman and Jim Wrenn and other related collections and published materials.

Recently, as part of a new project called “Print Culture of the Southern Freedom Movement,” SHC staff reviewed the contents of the GCRF records and this search surfaced a group of rare and unique bibliographic sources that offer important evidence of the labor organizing work that several of the Greensboro Massacre victims were doing in the years and months leading up to November 3, 1979. We’ll share some samples of the reports, union newsletters, flyers, and other sources and what they reveal about CWP’s involvement in organizing textile workers in North Carolina in the 1970s.

Dr. James Waller and the Granite Finishing Plant

Born in 1942, Jim Waller grew up in a Jewish household in Chicago. He later received his medical degree from the University of Chicago, trained as part of the Lincoln Hospital Collective in New York, and organized medical aid to American Indian Movement activists under siege at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in 1973. He relocated to North Carolina in the mid-1970s when he received a medical fellowship at Duke University.

His activism continued in the South. Waller organized with the Carolina Brown Lung Association, where he provided textile mill workers with health screenings for byssinosis (or brown lung) and helped develop health clinics. But in 1976, Waller decided to abandon the medical profession to become a textile mill worker at the Granite Finishing Plant in Haw River, N.C.

Waller was a member of the Workers Viewpoint Organization (WVO, later the Communist Workers Party) which believed in fomenting revolution through organizing rank-and-file workers. He began selling copies of the WVO’s newspaper outside of the gates of the Cone Mills-owned Granite Plant. He held training sessions for workers and shared educational literature to build up membership in Local 1113T of the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union (ACTWU).

Then, in the summer of 1978, Waller was fired by Cone for failing to list his medical training on his employment application. Waller claimed it was in retaliation for his union organizing work in the plant. In response, workers organized a twelve-day wildcat strike and held an election to establish new union leadership, since they felt that ACTWU was not doing enough to support the workers. Waller was elected president of Local 1113T. The strike brought renewed energy to the union and its member rolls grew from 15 to 200 members under Waller’s tenure.

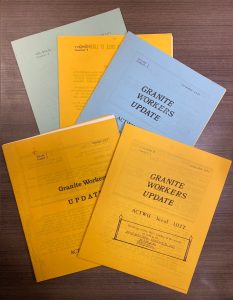

Jim and his wife Signe Waller produced and printed a newsletter, called Granite Workers Update, with a mimeograph machine they had at their home in Greensboro. Seven issues of the newsletter were printed during the strike. We uncovered copies of these issues of Granite Workers Update during our search of the Greensboro Civil Rights Fund Records and we are working on getting them cataloged as a separate serials title, to make them more accessible. According to the WorldCat library database, it appears that UNC Library holds the only extant copies of this newsletter.

Sandra Smith and the Revolution Mills

Like Jim Waller, Sandi Smith had medical training (as a nurse), a long history of activism, and an interest in organizing rank-and-file textile mill workers. Smith was a graduate of Bennett College in Greensboro, where she had served as president of the student body and a founding member of the Student Organization for Black Unity (SOBU). She was also a community organizer with the Greensboro Association of Poor People (GAPP). In the mid-1970s, Smith decided to become a worker at the Revolution Plant in Greensboro (also owned by Cone Mills Corporation) so that she could organize a union in the plant. She co-founded and was later elected chairperson of the Revolution Organizing Committee (ROC).

Under her leadership, ROC filed and won grievances with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) against unfair firings and arranged to have the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) inspect safety conditions at the mill for the first time in its history.

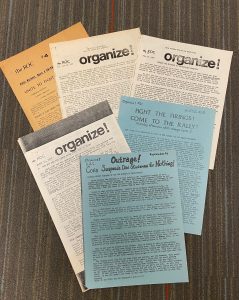

Those efforts are documented in a newsletter that ROC published throughout this period. We surfaced copies of the newsletter from our search of the GCRF collection and we will be cataloging and digitizing these to make them more widely available. They are believed to be the only extant copies of this union newsletter preserved by a library.

William Sampson and the White Oak Plant

Bill Sampson was born in Delaware in 1948. Active in the anti-war movement as an undergraduate student (and student body president) at Augustana College, Sampson spent his junior year studying at the Sorbonne in Paris, received a Masters in Divinity degree from Harvard in 1971, then studied medicine at the University of Virginia, where he organized health care workers to support liberation struggles in southern Africa.

Sampson left medical school to work and organize at the White Oak Denim Manufacturing Plant in Greensboro. Initially assigned to the dye house, which was a dirty and dangerous part of the denim manufacturing process, Sampson’s co-workers did not think he would last long in this role. But he stayed, working at White Oak for the last two and a half years of his life.

During that time, Sampson filed grievances on behalf of his fellow workers, he built up union membership, and fought unfair firings of fellow union leaders. He then ran for and was elected president of the union (ACTWU Local 1391). He was serving as president-elect at the time of his death.

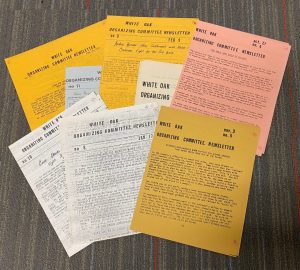

Sampson and the White Oak Organizing Committee (WOOC) published a union newsletter during this period. We discovered a near full-run of the publication during our search of the GCRF collection. Again, it is thought to be the only extant copy of the newsletter that is held by an academic library. We are working on cataloging and digitizing this newsletter to make it more broadly accessible to researchers.

Conclusion

These newly-discovered archival materials reveal important details about the lives and work of several of the activists killed on November 3, 1979, shedding new light on the intersections between racist violence, anti-Communism, and the labor movement in the South. We hope their re-discovery will inspire researchers to explore this and other lesser-known aspects of the legacy of the Greensboro Massacre.

Works Consulted:

Bermanzohn, Sally Avery. Through Survivors’ Eyes: From the Sixties to the Greensboro Massacre. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2003.

Chapman, John Kenyon Papers. Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC. https://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/05441/

Gateway, University of North Carolina at Greensboro Libraries. “The Greensboro Massacre.” Accessed November 2, 2023. https://gateway.uncg.edu/crg/essay1979.

Greensboro Civil Rights Fund Records. Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC. https://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/04630/

Greensboro Truth & Reconciliation Commission. “Final Report.” Accessed November 2, 2023. https://greensborotrc.org/index.php.

Magarrell, Lisa and Joya Wesley. Learning from Greensboro: Truth and Reconciliation in the United States. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

Waller, Signe. Love and Revolution: A Political Memoir: People’s History of the Greensboro Massacre, Its Setting and Aftermath.” New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002.

Workers World. “40th Anniversary of Greensboro Massacre provides lessons for today’s movement.” Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.workers.org/2019/11/44354/.

Wrenn, Jim Papers. Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC. https://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/05625/