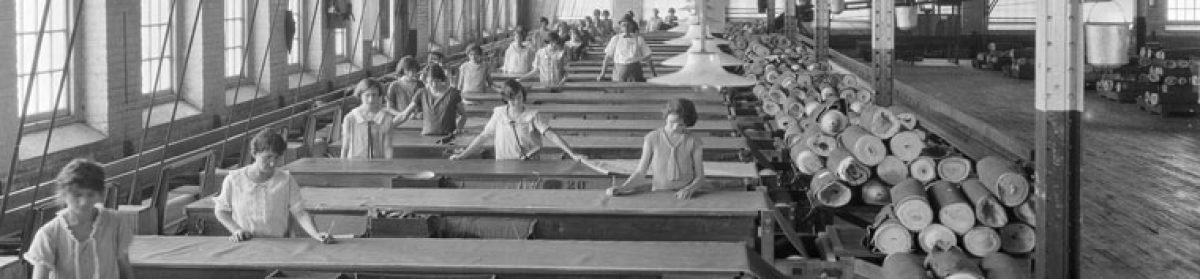

“It was in the textile mills of North Carolina [in 1934 that Martha Gellhorn, a 25-year-old investigator for the Federal Emergency Relief Administration] found the writing voice she had been looking for. It was clear and simple, a careful selection of scenes and quotes…. What made it her own was the tone, the barely contained fury and indignation…..

“Returning from a mill town where those fortunate enough to still have jobs were forced to pay half again as much for their food at the company store, she added: ‘It is probable — and to be hoped — that one day the owners of this place will get shot and lynched.’

“In Gastonia, among those who had lost everything, she at last had her subject. For the next 60 years, in wars, in slums, in refugee camps, she used this voice again and again…. It became her hallmark.”

— From “Gellhorn: A 20th Century Life” by Caroline Moorehead (2003)

Martha Gellhorn’s celebrated career as a foreign correspondent stretched from the Spanish Civil War to the invasion of Panama, although she is perhaps more widely remembered as Ernest Hemingway’s third wife — a distinction she abhorred.