The North Carolina Azalea Festival is in progress for the 72nd time in Wilmington. This year’s event takes place from April 3-7, 2019. Going back to 1948, not only is this event a celebration of flowers and golf, it brings celebrated guests from across the United States. From Hollywood movies, to TV stars, to celebrated sports heroes, the festival has seen them all. Over the years, many of the guests have made returned visits. This was especially true in the early years. As we celebrate festival number 72, Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard looks back at one of those guests, noted broadcaster Harry Wismer, who visited often during the1950s.

Hugh Morton crossed paths with legendary sportscaster Harry Wismer at the Sugar Bowl on January 1, 1949 in New Orleans. Wismer was in town to broadcast the game for ABC Radio between the UNC Tar Heels and the Oklahoma Sooners. Of course Morton was in town to photograph the game which featured his dear friend Charlie Justice. And as one would expect, Morton took at pre-game picture of Justice and Wismer, a picture that Hugh often included in his famous slides shows. Morton also included the image in his 1988 book Making a Difference in North Carolina on page 257.

Nearly two years later on December 10, 1950, Morton photographed the final regular season game between the Washington Redskins and the Cleveland Browns in Washington’s Griffith Stadium. Again, he crossed paths with Harry Wismer, the Redskins’ play-by-play man. At the time, Harry Wismer, who was known by many as “The Whiz,” was already considered the nation’s leading sportscaster, having broadcast numerous events like the National Open and PGA, the Penn Relays, and the National Football League Championship.

Wismer was also a part owner of the Detroit Lions and the Washington Redskins of the National Football League. In addition to his co-ownership, Wismer was “The Voice of the Redskins,” having called their games on the “Amoco-Redskins Network” since 1943. It was on those Redskins’ broadcasts that I first heard him. As a little kid, I listened to the Redskin games starting in 1950. When the game came to TV in North Carolina in 1951, Wismer was right there with the play-by-play. I remember those early broadcasts. Wismer’s commercial tag line went like this: “All around town, for all around service, visit your Amoco man, and Lord Baltimore filling stations.”

Starting in 1949, the Azalea Open Golf Tournament became a part of the spring festivities. Hugh Morton invited Wismer to the 1950 Azalea Festival in Wilmington, along with Southern Methodist University football hero Doak Walker and his wife Norma. Of course, Tar Heels Charlie and Sarah Justice returned in ’50, having been there in 1949 to crown Azalea Queen II, Hollywood starlet Martha Hyer. When Justice and Wismer returned to Wilmington for the 1951 festival, Hugh Morton had added a new event: a special golf match at the Cape Fear Country Club called “Who Crowns the Azalea Queen?” The match pitted two ABC Radio broadcasters, Harry Wismer and Ted Malone, against two football greats, Charlie Justice and Otto Graham.

The winner of the nine–hole–event would have the honor of crowning Queen Azalea IV, Margaret Sheridan. The ‘51 winner was the Justice/Graham team.

In addition to being part of the parades, flowers, and parties, Wismer broadcast the Azalea Open Golf Tournament on ABC Radio. The 1951 Open winner was Lloyd Mangrum, and Wismer included an interview with him on his ABC Radio show which was also originated live in Wilmington.

The 1952 “Who Crowns the Azalea Queen?” event once again put Wismer’s team, which included writer Hal Boyle and band leader Tony Pastor, against a football squad of Charlie Justice, Eddie Lebaron, and Otto Graham and this time the Wismer team won.

According to Hugh Morton, the original queen selection for 1952 was actress Janet Leigh, but her husband Tony Curtis decided to cancel their trip to Wilmington. Morton knew that actress Cathy Downs was in town because her husband Joe Kirkwood, Jr. was playing in the Azalea Open. When Morton invited her, she accepted and became Queen Azalea V.

Wismer continued his Azalea Festival visits during the mid-1950s. Charlotte broadcaster Grady Cole also participated in Wismer’s broadcasts.

Wismer would later become one of the founding fathers of the American Football League, which began play in 1960; three years later, however, he gave up his football leadership. Wismer spent the remainder of his life trying to reclaim his glory days as broadcaster and team owner, but was unsuccessful partly because of his declining health. In 1965, Wismer wrote a book titled The Public Calls It Sports. In it he gives a “behind the scenes” look at professional football from a broadcast and ownership point of view.

Harry Wismer passed away on December 4, 1967, the day after a tragic fall at a New York restaurant. He was 64-years-old.

Stephen Fletcher

A Midwest conquest

On March 18th, 2012 Bill Richards, a colleague who worked in the library’s Digital Production Center, passed away unexpectedly while watching the Tar Heel’s basketball team defeat Creighton University in the “Sweet Sixteen” round of the NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament. In 1982, Bill was the Chief Photographer for the Chapel Hill Newspaper. In 1988, he began working as a photographer and graphic designer in the UNC Office of Sports information. In 1998 he started working in Library Photographic Services, but continued shooting for Sports Information into the 2000s. I am dedicating this blog post, as I have each year since his departure, to Bill who, like Hugh Morton, was an avid UNC basketball fan.

This year poses a bit of a challenge for this annual blog post: the NCAA Tournament has yet to begin. Where then shall we go to celebrate, Bill? I know . . . midwest!

Yep. it’s NCAA Men’s Basletball Tournament time. Were it not for two teeny tiny points, UNC might be heading up the East Regional bracket. Instead, the Tar Heels find themselves atop a different bracket farther west—the Midwest, to be exact. Haven’t we been here before? Yes, and just like this year, Carolina did not win the ACC Tournament played in Charlotte.

In the 1990 NCAA Tournament, the Tar Heels took off for Austin, Texas as the bracket’s eighth seed. First up: ninth seeded Southwest Missouri State University (now known as Missouri State University). The Tar Heels handily beat the Bears by thirteen points, 83-70. Next on the docket: number one seed Oklahoma, ranked first in the nation in the final Associated Press Coaches Poll (through March 11) with its 26-4 record. By comparison, UNC with its 19-11 record was unranked—its worst season in twenty-six years despite defeating the fifteenth-ranked Duke Blue Devils twice during regular season play.

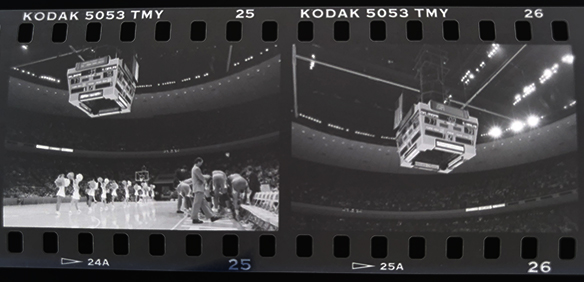

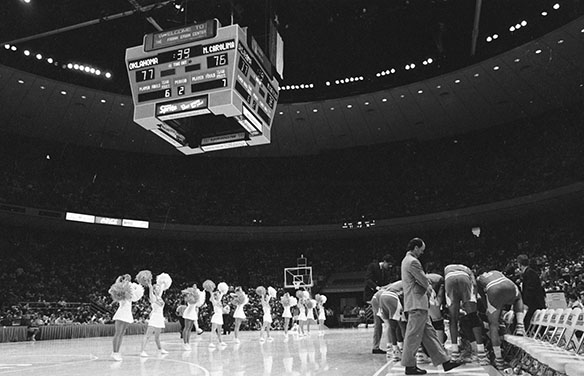

The limited time I have available does not permit me to recount the game’s highlights, but the photographs below tell some of the closing story. The first frame, Frame 24A, depicts the time out called by Carolina at the 0:39 second mark after Oklahoma’s William Davis converted his “and-one” free throw for a three-point play to take the lead 77-76. After the break, the Tar Heels struggled to make anything to happen. Dean Smith tried to get someone’s attention to call a timeout, but before that could happen, an Oklahoma player fouled King Rice with 0:10 on the clock. A timeout did take place, after which Rice tied the game by making his first “one and one” foul shot.

“Tied,” declared CBS play-by-play announcer Brent Musberger.

King’s second shot was off the mark, and the ball rebounded high off the rim. No one could reel in the rebound before an Oklahoma player knocked the ball out of bounds under the basket.

Dean Smith called for a timeout, during which he drew up a play designed to get the ball in the hands of Rick Fox, the Tar Heel’s three-point marksman with twenty-one points in the game to that point. Fox recounted after the game what Dean Smith told him during the timeout: “‘Rick, remember, we don’t need three. We only need one.'”

Fox got two, with a quick fake of a three and a drive down the baseline to make the layup with only one second remaining. Morton’s second frame shows the outcome.

There are no negatives or color slides of the ensuing play, with no missing frames or 35mm color slides. But when the clock reached 0:00, Morton recorded the final score: UNC 79 Oklahoma 77.

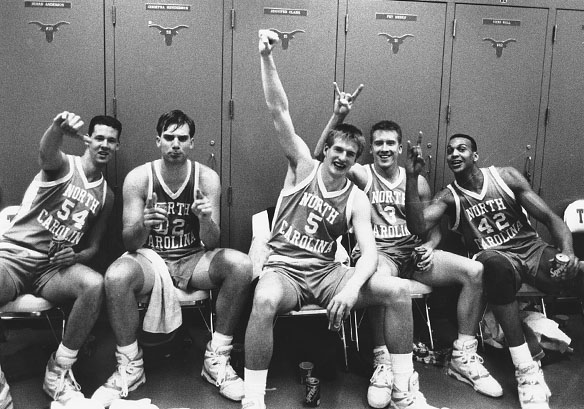

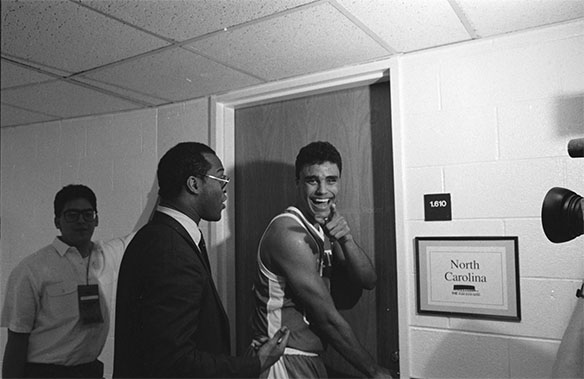

Morton also shot a few frames of the celebration on court, then made his way to the locker room for the celebration.

Here’s looking at you, Bill.

The father of big-time basketball in North Carolina and the South

The ACC Men’s Basketball Tournament begins today and “March Madness” is on our doorstep. Once again the Atlantic Coast Conference is evenly balanced and is predicted to be a NCAA leader. There was a time before the conference was born, however, when basketball in North Carolina and the South was secondary to football. Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard takes a look at the man and the tournament that brought about the roundball prominence we see today.

I remember a time in 1954 when I was a freshman in high school and working for my dad at his drug store in Asheboro. He had just hired a guy named Johnny Campbell, an Army veteran who had recently returned from three years (1951–1953) in Germany and Korea. Campbell told me once that most everywhere he went, when people learned he was from North Carolina, they would say “NC State basketball, Everett Case.”

Coach Everett Case was a basketball visionary long before he came to North Carolina State in 1946. Back in his native state of Indiana, he was a legendary high school coach. When he arrived in North Carolina, football was king; Case, however, saw basketball as king, and he began to change the minds of fans across the state. He saw a partially built Reynolds Coliseum as an arena of 12,500 cheering fans.

In the beginning, Case recruited many out-of-state players, but he visited North Carolina high schools across the state, encouraging coaches and school boards to build better gym facilities so young boys could compete for basketball scholarships.

In his first season at State, the fire marshal canceled a game because people were spilling onto the floor and climbing in the windows of tiny Thompson Gymnasium. Case described that scenario in a 1964 interview: “We played our first games in Frank Thompson Gym, and had to cancel the North Carolina game when the students broke down the doors and the fire marshal wouldn’t let us play.”

That 1946–47 NC State team compiled a 26 and 5 record, and won the Southern Conference Tournament beating Maryland, George Washington, and North Carolina.

Then, it happened again during the 1947-48 season:

The fire marshal called off our Duke game in Frank Thompson Gym on the afternoon it was scheduled to be played. . . They said Frank Thompson Gym was a ‘fire hazard’ and wouldn’t let us play any more home games there . . . so we had to move into Memorial Auditorium.

State racked up an even better record of 29 and 3 during the 1947-48 season, and once again won the Southern Conference Tournament—this time beating William and Mary, North Carolina, and Duke. By the 1948-49 season, NC State basketball was becoming extremely popular, just as Case had envisioned, as they won yet another Southern Conference Championship.

NC State moved into the William Neal Reynolds Coliseum for their home games during the 1949–50 season, and saw the establishment of a holiday basketball tournament that quickly became the top sporting event in North Carolina. It was called the “Dixie Classic.” As Case said, “All the Big Four schools were tickled to get in on it . . . it meant some big pay-checks for them.” And as you might have guessed already, State won the first Dixie Classic as well as the 1949–50 Southern Conference Championship.

I recall seeing my first Dixie Classic. I had never seen anything like it. The house lights in the Coliseum were dimmed and a spotlight was turned on for the player introductions, and when it was all over the winning team cut down the nets. The names Dick Dickey and Sam Ranzino were fast becoming heroes for kids across the state.

Case’s 1950–51 team brought home another Southern Conference and a second Dixie Classic Championship, winning 30 games. Finally, during the 1952–53 season, Wake Forest nipped State 71 to 70 for the Southern Conference Championship, but State won its fourth Dixie Classic.

The 1953-54 basketball season in North Carolina brought a new conference to town: the Atlantic Coast Conference. NC State suffered two losses in the Dixie Classic—one to Navy and one to Wake Forest—but they won the first ACC Tournament Championship.

The 1954-55 Wolfpack continued their winning ways with the Dixie Classic and ACC Championships. It was ditto for the next two seasons, and it was beginning to look like Coach Case and his Wolfpack would dominate the ACC as it had the Southern Conference. But in 1956, the momentum was derailed when NC State was placed on a four-year probation by the NCAA. It was reported that an assistant coach and State’s assistant athletic director had given a Louisiana high school kid cash and gifts to entice him from his previous agreement to attend Kentucky. Case denied the charge, but the NCAA ruled that he knew about the gifts—which included a seven-year medical education. This became known as the Jackie Moreland case.

The 1956-57 NC State team lost to Wake Forest in the Dixie Classic and the ACC Tournament. The 1957-58 Wolfpack lost both tournaments as well, this time to powerful North Carolina, who compiled a 32-and-0 record and won the NCAA Championship.

Case and his Wolfpack came back to win the ACC Tournament following the 1958-59 regular season as well as the 1958 Dixie Classic, but lost both events in the 1959-60 season. There were no NC State tournament wins during the 1960-61 season. Following the season, it was revealed that at least four NC State players and possibly two UNC players had shaved points in order to shade the outcome of games, including at least one Dixie Classic game. Said Case, “it was a terrible blow to all of us here at State.”

The 1960 Dixie Classic was the last to be played, because things got worse. On Saturday morning, May 14, 1961, Lester Chalmers, Wake County’s district solicitor called UNC President Dr. William Friday to an an emergency meeting. Chalmers told Friday that a player’s life had been threatened by gamblers. “In our minds, we were dealing with protection of human life of an innocent college kid . . . you weren’t left with any alternative.” The UNC system imposed numerous sanctions on both UNC and NC State’s basketball programs and abolished the Dixie Classic.

Due to the scandals, State played fewer games during the 1961 through 1964 seasons, with no ACC Championships. By this time, Coach Case was in failing health, but he began the 1964–65 season even though he was suffering inoperable cancer. Two games into the season, he was unable to continue and turned the coaching over to assistant Press Maravich. When State won the 1965 ACC Tournament, Coach Case was taken in his wheelchair out to help the team cut down the net. A year later, Everett Case died and was buried in Raleigh’s Memorial Park. It was his wish to be laid facing US Highway 70 so he could “wave” to later NC State teams as they traveled to Durham and Chapel Hill.

In his time at NC State, Everett Case’s resume is like no other. He won 379 games, six Southern Conference Championships, four Atlantic Coast Conference Championships, and seven Dixie Classics. During his career the ACC named Case as its Coach of the Year three times. Through all those accomplishments, he brought big-time basketball to North Carolina and the South.

Afterword from the Editor

In searching for images to illustrate this post, I’ve discovered that Hugh Morton images for the Dixie Classic and from the early years of the ACC Tournament are sparse. The earliest identified Dixie Classic negatives date from 1957 through 1959, while those depicting the ACC Tournament images date from 1958. Earlier images may exist, but the dates are uncertain. In fact, 1950s college basketball negatives by Morton are a relative scarcity. Many negatives listed in the finding aid for this decade are broadly categorized, such as “Old basketball negatives” or (take a deep breath . . . ) “College basketball, various (North Carolina State University vs. William & Mary, George Washington vs. William & Mary, North Carolina State University, Wake Forest, Greensboro, Maryland, other unidentified teams), 1940s-early 1950s.” Perhaps one day we’ll be able to sort out the images with a bit more specificity.—Stephen

Our time with Woody

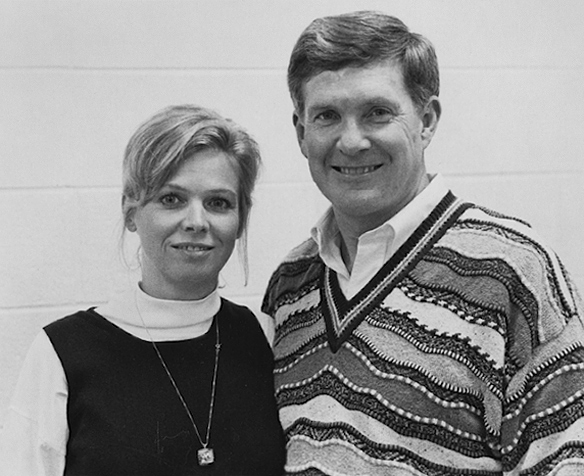

It was one year ago today, March 7, 2018, that we received the sad news that Woody Durham had lost his gallant battle with primary progressive aphasia, a neurocognitive disorder that affects language expression. On this first anniversary of his passing, Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard looks back on our time with Woody.

Prolog

If you search the online collection of Hugh Morton photographs, you will find two dozen Morton photographs that include Woody Durham. If you search the collection finding aid, you will find many more. Woody was a favorite Morton subject, so when Bob Anthony and Stephen Fletcher, of the Wilson Library’s North Carolina Collection, put together a panel at Appalachian State in October of 2013 to discuss Morton’s work, Woody was an important participant.

As the 2010-11 college basketball season turned into that famous March Madness, it looked like Carolina might be headed to yet another final four. With wins over Long Island, Washington, and Marquette, they were in the “Elite Eight”® and playing Kentucky for another Final Four trip. It was Sunday afternoon, March 27, 2011 . . . Number 2 seed UNC against Number 4 seed Kentucky . . . at the 18,711-seat Prudential Center in Newark, New Jersey. Woody Durham was calling game number 1805 as the Tar Heel “Voice.” The winner would capture the East Regional bracket and advance to the Final Four in Houston. A Tar Heel win would give Woody an opportunity to call his fourteen Final Four. But sadly for those of us listening to Woody and watching CBS Sports, it wasn’t to be.

The Tar Heel Nation was stunned as Kentucky came away with the win, 76 to 69. We didn’t know it at the time, but we suffered another loss that afternoon: it would be Woody Durham’s final play-by-play broadcast after forty years as the “Voice of the Tar Heels.” The official announcement came twenty-four days later. After calling 1,805 football and basketball broadcasts, Woody Durham was signing off.

***

From 1971 until 2011, Woody Durham was the soundtrack for Tar Heel football and basketball. During that span

- the National Sportscasters and Sportswriters Association selected Woody as the North Carolina Sportscaster of the Year thirteen times;

- he was the voice for six national championship games and thirteen Final Fours;

- he called twenty-three football bowl games; and

- he interviewed six Tar Heel head football coaches and four head basketball coaches.

His game-day-preparation was legendary and his attention to detail with his color-coded information charts became famous. But Woody Durham was much more than the voice of his university. He often headed up life-long-learning programs for UNC’s General Alumni Association and was a program fixture during Graduation-Reunion weekend each May. He traveled across his native state speaking to Tar Heel alumni groups.

Following his retirement, Woody and his wife Jean attended most of Carolina’s football games, and were always seated in Section 212 Row C in the Smith Center for Tar Heel basketball games. Then, in 2015, Woody began to lose his ability to speak. The following year, came the diagnosis: Primary Progressive Aphasia. But as you might expect, Woody took up the cause and became a leader educating his many fans about the disease.

On March 7, 2018 came the news report that Woody had lost his battle.

I think UNC Head Basketball Coach Roy Williams said it best when he issued this statement:

“It’s a very sad day for everyone who loves the University of North Carolina because we have lost someone who spent nearly 50 years as one of its greatest champions and ambassadors. . . . My heart goes out to Jean, Wes, Taylor and their entire family. . . . It’s ironic that Woody would pass away at the start of the postseason in college basketball because this was such a joyous time for him. He created so many lasting memories for Carolina fans during this time of year. It’s equally ironic that he dealt with a disorder for the final years of his life that robbed him of his ability to communicate as effectively as he did in perfecting his craft.

Woody Durham will forever be “THE Voice of the North Carolina Tar Heels.” Others will broadcast the games and will do a really good job, but Woody will be the one we all remember.

It's been quiet here, but not behind the scenes

Belated Happy New Year!

For the past year or so, it has been really difficult for me to write blog posts for A View to Hugh on a regular basis. Thank goodness for Jack Hilliard’s continued interest in writing for the blog! If you are a regular reader, you might be wondering why it has been relatively quiet here. You might even be thinking that, eleven years after this blog’s debut in November 2007, there isn’t much work being done with the Morton collection. If fact, just the opposite is true. I worked extensively with the Morton collection during 2018. In honor of what would be Hugh Morton’s 98th birthday today, let me share with you what I have been doing to extend the life of his photographic negatives.

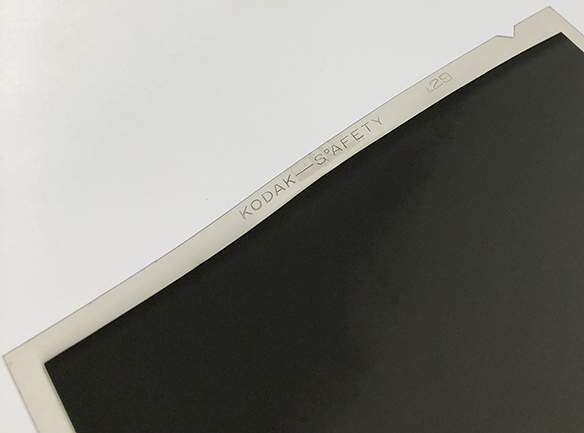

Morton’s film negatives and color transparencies dating from the late 1930s through the early 1960s are physically made of cellulose acetate film stock. The common name for these various acetate negatives is “safety film” because it replaced cellulose nitrate film stock, which is highly flammable. Many brands of film from that time period have the word SAFETY imprinted onto the edge of the film. Kodak issued its first safety film in 1926, but they became more common in the marketplace by the early to mid 1930s. They coexisted for several years with their cellulose nitrate brethren. Adding SAFETY to the sheet films’ edges distinguished them from their predecessor films made using cellulose nitrate, which then began to have the word NITRATE on their edges.

A keen eye will notice in the negative seen above that its edge has a slight wave. If you follow the links to the Wikipedia entries in the previous paragraph about these film bases, you may read more about how they deteriorate. For acetate films, basically, the negative begins to distort as the cellulose acetate base layer begins to break down, eventually causing its base to separate from the emulsion layer. The first stage of deterioration is a symmetrical curling of the film edges, meaning the curls are the same on opposite sides of the negative. This can go undetected if the collection is not used or inspected routinely.

Typically one’s nose is the first to detect that deterioration has begun. When the chemical composition of the cellulose acetate degrades to a certain level, the film emits the smell of vinegar—acetic acid. The next stage of deterioration is an asymmetrical warpage of the negative: where the curling is “upward” on one edge, it is “downward” on the opposite edge. Often, but not always, small bubbles will appear. Finally, the emulsion layer and the film base separate from each other.

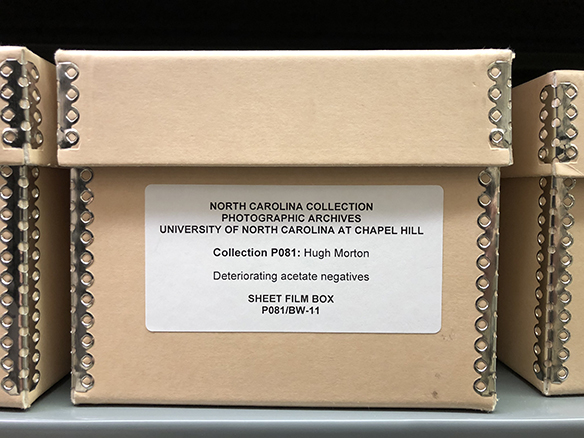

We detected that some acetate negative deterioration had already taken place in the Morton collection before it arrived at Wilson Library, although the problem was not widespread. We removed those negatives that were already deteriorated and those that exhibited the early stages of deterioration into a separate box during archival processing. We did that in order to isolate the bad from the good, because the deterioration process is autocatalytic and thus can cause nearby good negatives to deteriorate. If you look in the Morton collection finding aid, you will see several entries with the phrase “removed to Sheet Film Box P081/BW-11 due to acetate deterioration.”

Storing negatives in a warm and/or humid environment exacerbates the deterioration process. A cool, dry environment slows down the process; only storage at zero degrees Fahrenheit, however, will impede the process.

Acetate deterioration became known to film manufacturing industry in the late 1940s. Manufacturers developed a replacement made from polyester during the early 1960s. Polyester films are remarkable stable.

The traditional method to preserve images on nitrate and acetate film negatives has been to make duplicate film copies using the interpositive method. An unexposed polyester film negative is placed in direct contact, emulsion to emulsion, to the acetate or nitrate negative, then properly exposed to light and chemically developed using archival film processing techniques. A negative film stock exposed to a photographic negative, produces a positive, which is then used to expose it to another sheet of unexposed film to make a duplicate negative—hence the word interpositive.

Vendors who make preservation duplicates using film today are rare and the cost is prohibitive because film and processing chemistry are no longer readily available. As you probably guessed, the duplication method has been replaced by digital technology. But it was not until September 2016 that an agreed upon standard—the Federal Agencies Digital Guidelines Initiative (FADGI)—determined specifications deemed acceptable for preservation digitization. That high level of preservation digitization is called FADGI 4-star.

In mid November 2016, the North Carolina Collection received a significant donation from the Ellis and Rosa McDonald Fund for Excellence to provide continued support of the Hugh Morton collection preservation project. I embarked on a pilot project with Chicago Albumen Works using a representative sample of negatives of different formats (3×4-inch negatives, 4x5s, 35mm, as examples). After completing the pilot project, I decided to focus on Morton’s earliest work, typically 3×4 negatives before he routinely used 4×5 starting in the early 1950s. I then moved to the 4×5 negatives made until the transition from acetate film to polyester film stocks in the early 1960s.

For both formats I needed to determine the negatives’ condition and—because we couldn’t possibly digitize every negative in the collection—the importance of their subject matter and the image quality of the negatives. To keep track of selections sent to the vendor, I created a spreadsheet that also helped me to standardize the file names for the scans to be typed by the vendor during production. In summary, Chicago Albumen Works digitized nearly 2,950 negatives at FADGI 4-star quality.

All that represents a significant amount of work that kept me from putting together blog posts. One post did emerge from the process when I discovered the negatives of Gerald P. Nye’s visit to UNC, and another post about Alton Lennon is waiting in the wings. This post is getting a bit long, however, so I’ll stop here and save additional details about the preservation digitization project for a future peek “Behind the Scenes.”

A call to the Hall for coach Mack Brown

Editor’s Note

This post is a follow-up to the post, “Mack Brown’s Return to Kenan Stadium” published on September 11 earlier this year. As we were preparing today’s post honoring Mack Brown for his induction into the National Football Foundation’s College Football Hall of Fame, UNC and Chancellor Carol Folt and Athletic Director Bubba Cunningham announced during a noontime press conference on November 27 that Brown will return to coaching duties for Carolina. Brown then stepped to the podium and addressed the gathered media. “Sally and I love North Carolina, we love this University and we are thrilled to be back. The best part of coaching is the players—building relationships, building confidence, and ultimately seeing them build success on and off the field. We can’t to wait to meet our current student-athletes and reconnect with friends, alumni and fellow Tar Heel coaches.”

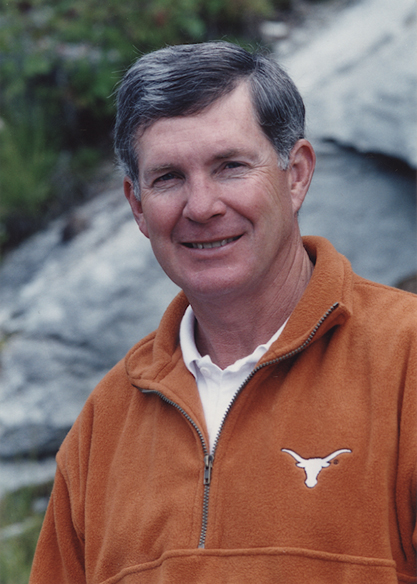

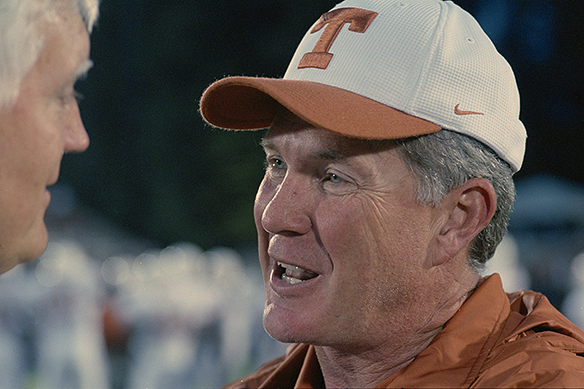

On December 4, 2018, former Head Football Coach Mack Brown will become the twelfth UNC Tar Heel and the twenty-second Texas Longhorn to be inducted into the National Football Foundation’s College Football Hall of Fame. The dinner ceremony from 8:30 p.m. until 11:00 p.m. EST can be watched via a livestream on ESPN3. Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard takes a look at Brown’s thirty-year head coaching career.

When it’s all over, your career will not be judged by the money you made or the championships you won. It will be measured by the lives you touched. And that is why we coach. —Mack Brown in One Heartbeat (2001), page 173.

It was November 18, 1989. Tar Heel head football coach Mack Brown had just suffered one of the worst defeats of his entire coaching career at the end of a second 1-and-10 season. But Brown felt a personal obligation to come back up on the Kenan Stadium field because the Raycom TV crew wanted one more seasoning-ending interview. By the time Brown finished his locker room and media conference duties, the late November sun was setting far beyond the west end of the historic stadium, and most all of the 46,000 fans who had filled the stands earlier had headed home. About midway through the interview, Brown was distracted by cheering from the far end zone. He turned and looked. What he saw was unbelievable. Duke head coach Steve Spurrier had come out of the visitor dressing room and assembled his team around the still-lighted scoreboard, which read 41 to 0. The Blue Devil photographers were snapping away. Brown paused for several seconds, and then said, “We’ll remember that.” Coach Brown never lost again to Duke University during his entire coaching career.

Mack Brown began his successful head-coaching career at Appalachian State in 1983, leading the Mountaineers to a 6-5 record—their first winning season in four years. Then following a successful season as the offensive coordinator at Oklahoma under Hall of Fame coach Barry Switzer, he became the head coach and athletic director at Tulane in 1985, where he led the Green Wave to a 6-6 record in his final season in 1987 and earned a trip to the Independence Bowl. It was only the fifth bowl appearance for Tulane since 1940.

Following his time at Tulane, Brown was hired by UNC Athletic Director John Swofford, just in time for the big 100th anniversary of Carolina football during the 1988 season. But those first two seasons at Carolina were dreadful, showing only two wins and twenty losses. With the 1990 season, however, things were turned around and during the next eight seasons, Brown added sixty-seven additional wins—tied for the second most victories in school history. The team was bowl-bound every year beginning in 1992, including a win in the 1993 Peach Bowl. The Atlantic Coast Conference named Brown ACC Coach of the Year in 1996. Brown led Carolina to three ten-win seasons, while the team finished in the top twenty-five four times, including tenth in 1996 and fourth in 1997.

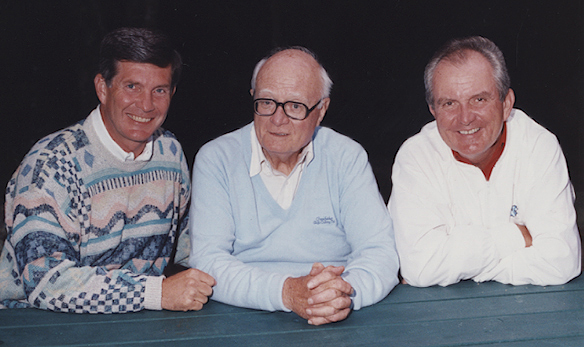

During his time in Chapel Hill, Brown became good friends with Hugh Morton and visited often at Grandfather Mountain. In fact, Brown built a home there. And he was instrumental in the construction of another home . . . this one in Chapel Hill and it goes by the name Frank H. Kenan Football Center, completed in 1997.

It was Saturday, September 13, 1997. Carolina was hosting a late afternoon game with Stanford. Coach Brown and one of his assistants, Cleve Bryant, who had been an assistant at Texas, were on the Kenan field watching the Tar Heels warm up, when on the stadium public address system, announcer Dave Lohse started giving some scores from the early games. He then gave a halftime score: UCLA 38, Texas 0.

Said Bryant, “that can’t be right.” Coach Brown didn’t pay much attention; he was intent on the game at hand. About two hours later, up in the Kenan press box, UNC Sports Information Director Rick Brewer handed some final scores to announcer Lohse. As he did so, he said. “I think we just lost our football coach.” Brewer was fully aware of Brown’s admiration for Texas football history and tradition. Lohse then read the final score: UCLA 66, Texas 3. When Bryant heard that score, he turned to Brown and said, “I wouldn’t want to be in Austin, Texas tonight.” From that moment, for the next eighty-four days, speculation was rampant: would Mack Brown leave a place he dearly loved, for an opportunity of a lifetime? Finally, on Wednesday, December 3, 1997 it became official: Mack Brown would be the new head football coach at the University of Texas.

Coach Brown’s time in Austin was legendary. His 158 career Texas wins are second only to Hall of Fame Coach Darrell Royal in Longhorn history. During the 2005 season, Brown guided Texas to its first national championship in 35 years after defeating Southern California in the 2006 Rose Bowl in one of the greatest games in college football history. In 2009, Brown became Big 12 Coach of the Year while winning his second conference title. He would become a two-time National Coach of the Year and won more than 10 games in 9 consecutive seasons. He also won 10 bowl games while in Texas.

Over his 30-year-coaching-career, Brown coached 37 First Team All-Americas, 6 Academic All-Americas, 110 first team all-conference selections and 11 conference Players of the Year. He also coached 2 College Football Hall of Famers in Tar Heel Dre Bly and Heisman Trophy winner Ricky Williams at Texas; and 4 National Football Foundation National Scholar-Athletes, including Campbell Trophy winners Sam Acho and Dallas Griffin also at Texas. Brown posted 20 consecutive winning seasons from 1990 to 2009 and his 225 wins from 1990 to 2013 were the most among Football Bowl Subdivision coaches during those years. He has a total of 244 wins—tenth most by a coach in FBS history. He led teams to 22 bowl games.

Among his personal honors, Brown is a member of the Texas Longhorns Hall of Honor. He is also enshrined in the Rose Bowl, State of Texas Sports, State of Tennessee Sports and Holiday Bowl halls of fame. Until November 27th, he served as a college football studio and game analyst at ESPN and served as a special assistant at Texas.

Mack Brown and wife, Sally, have helped raise millions of dollars for children’s charities, and Mack was recently named the Football Bowl Association’s Champions Award recipient for 2019. He was also honored in the Blue Zone at Kenan Stadium on Saturday, August 12, 2018 for his upcoming December 4th induction into the College Football Hall of Fame.

Toward the end of the Blue Zone ceremony, Brown came to the podium and acknowledged many Tar Heels in the audience. There was John Swofford, the Carolina athletic director who hired him and then after those 1-10 seasons gave him a contract extension. There were former assistant coaches Darrell Moody and Dan Brooks, who had been so very important in those early recruiting efforts. And there were former Tar Heels from eras before Brown arrived as a 36-year-old head coach. “You guys were the ones who made this place special and gave us something we could sell,” Brown said.

There were about fifty Tar Heels present from Brown’s time in Chapel Hill. Also in attendance was UNC 1970 All-America Don McCauley who is also a College Football Hall of Famer, Class of 2001.

“I’m not going into the Hall of Fame, I am presenting you all in the Hall of Fame. Football is the ultimate team sport, and no one person is ever the one that wins a football game. When I take that oath in December and I say ‘thank you’ to the Hall of Fame, I’m doing it for each one of you. Your name in my mind will be in the Hall of Fame forever.” Carolina Athletic Director Bubba Cunningham added, “Brown’s legacy wasn’t just about winning; it was about developing young men to be successful after football.”

Part of the celebration was a panel discussion with several former Tar Heel players talking about Brown and his Chapel Hill legacy. One of those players was fellow Hall of Famer Dre Bly who spoke of getting a sideline dressing down in his first game as a Tar Heel in the 1996 season opener against Clemson, a 45-0 Tar Heel landslide.

“The play was on our sidelines, a ball into the flat. I made a big hit. I was high-stepping and celebrating. Coach Brown grabbed my facemask and had a few select words for me. He said, ‘We don’t do that here.’ I knew then and there, I had to remain humble. I learned the importance of being humble. I saw the big picture, I understood what’s important. We had a very talented team. I couldn’t be the one to mess it up. I needed to remain humble, and I’ve used that my whole life.” (I wish the UNC head football coaches that followed Brown would have maintained that same high standard.)

I believe it’s safe to say, whether you view it as Burnt Orange or Carolina Blue, Brown’s legacy is secure, and on Tuesday night, December 4, 2018, he will stand for the administration of his induction as the citation of his accomplishments is read—this year in the Trianon Ballroom of the New York Hilton Midtown, just as coach Darrell Royal and Bobby Layne of Texas and coach Carl Snavely and Charlie Justice of Carolina stood years before in the Grand Ballroom of the historic Waldorf-Astoria—as William Mack Brown will be honored as a new member of the College Football Hall of Fame. Coach Brown will make the official response on behalf of the 2018 College Football Hall of Fame Class.

A golden celebration

Prolog:

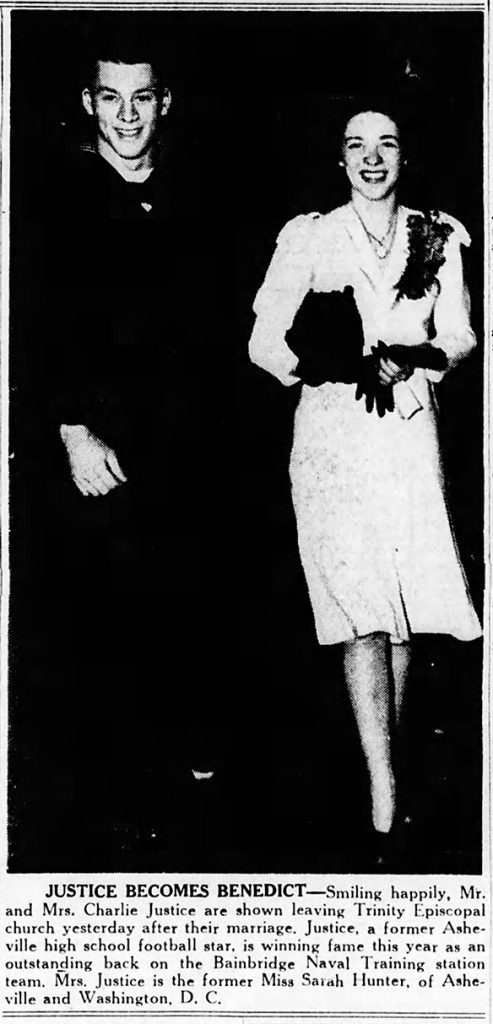

Ten days after future UNC football legend Charlie Justice led his undefeated Bainbridge Naval Training Station football team to a 46-to-0 win over the University of Maryland, he went on a well-deserved leave. At the same time, Sarah Alice Hunter took a brief leave from her job at the Naval Observatory in Washington, D. C. The two headed back home to Asheville, North Carolina where they were married at Trinity Episcopal Church.

During the next 59 years, 10 months, and 23 days, Charlie Justice would be interviewed numerous times. During most of those interviews, he would, at some point, say “the best thing I ever did was to ask Sarah to marry me.”

Intro:

They played the 80th meeting between Carolina and Duke on November 26, 1993—a chilly, gray Friday morning—at 11 o’clock. My guess is that ABC-TV wanted it played on that day at that time. As it turned out, that was a good thing because the game ended about 2:30 PM, in plenty of time for a very special celebration in “the living room of the University” across campus.

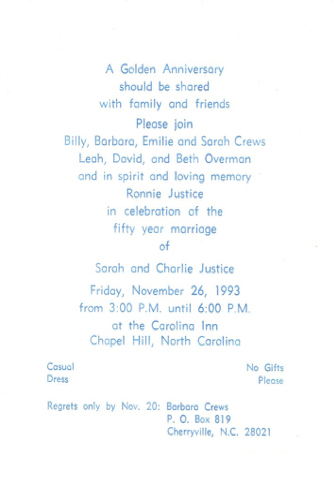

Today, on the day Charlie and Sarah Justice would have celebrated their 75th wedding anniversary, Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard looks back 25 years at their 50th celebration.

A few minutes after Carolina beat Duke 38 to 24 in the 1993 edition of their annual in-state rivalry, (thanks to freshman running back Leon Johnson’s 142-yard-and-4-touchdown day), many of us headed across campus to the historic Carolina Inn, where family and friends of the special couple were gathering. Although Charlie and Sarah Justice’s fiftieth wedding anniversary was actually on November 23rd, game day on the 26th seemed like a good time to celebrate the storybook event of November 23rd, 1943.

In addition to celebrating the Justice’s fiftieth anniversary, the event also honored the memory of their son Charles Ronald (Ronnie), who had passed away on Friday, June 11, 1993 at their home in Flat Rock, North Carolina.

This is how the Justice’s chose to invite their guests:

There were family members, teammates, friends, and fans in attendance.

The Carolina Inn ballroom provided the perfect backdrop for the elegant event and the many guests surrounded a large buffet table with roast beef, salmon, fruits, and cheeses. The centerpiece was a large ice sculpture depicting a locomotive celebrating Charlie’s football career when he was called “Choo Choo.”

At the right side of the room was a video player and large screen where highlights of Charlie and Sarah’s fifty years together were shown. I had the honor of producing that video presentation which was narrated by North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame broadcaster Charlie Harville.

Following a family toast by Barbara (Justice) Crews, Charlie and Sarah’s daughter, head football coach Mack Brown added his congratulations and then offered an additional toast. He then spoke of the importance of Carolina’s football history and heritage. After Brown concluded his words about Carolina’s Golden Age during the late 1940s, Justice stepped forward and thanked the coach for restoring football respectability “for my University.”

During the entire celebration, photographer Hugh Morton was there documenting every phase of the event: from a group shot of the Justice team mates to a funny shot of Charlie and Sarah holding up special tee shirts prepared for the party, a shot that appeared in the February, 1994 edition of The University Alumni Report newspaper on page 34.

So, on this day, November 23, 2018, I choose to believe that Charlie and Sarah Justice are once again celebrating their storybook life together on their 75th wedding anniversary. Joining the celebration is son Ronnie, and just as he was 25 years ago, Hugh Morton is there with camera in hand.

Fiery "America First" Dakotan takes on Tar Heels

The controversy between isolationists and interventionists became an unusually rugged affair with no holds barred on either side. . . . The name-calling, mud-slinging, and smearing on both sides made the foreign policy debate a poor place for the sensitive or fainthearted. Each side welcomed almost any chance to discredit the opposition.

—Wayne S. Cole in Gerald P. Nye and American Foreign Relations

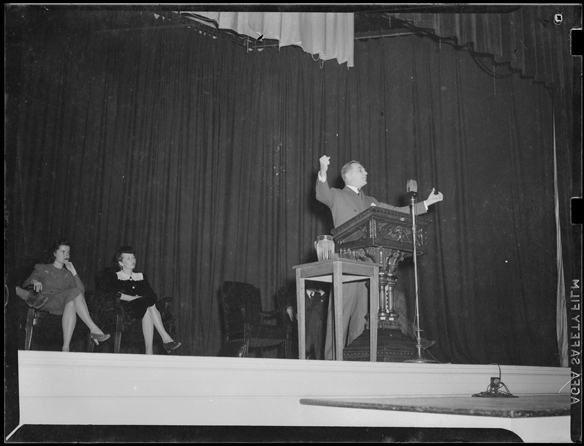

It was Armistice Day—Tuesday, 11 November 1941— and United States Senator Gerald P. Nye’s speech at the University of North Carolina, announced to the student body that day—was still a week away. Despite the frivolity of Sadie Hawkins Day events during the weekend, peace was not on the horizon. In the opening sentence of his front-page article of The Daily Tar Heel, writer Paul Komisaruk predicted the nature of the upcoming event:

National politics and policies erupt from the Memorial hall rostrum next Tuesday night as North Dakota’s Old Guard isolationist, Senator Gerald P. Nye, attacks New Deal measures before a Chapel Hill audience under the auspices of the CPU [Carolina Political Union].

On that same November 11th evening, Vichy France‘s ambassador to the United States, Gaston Henry-Haye, was the International Relations Club (IRC) speaker at Memorial Hall. Appointed by Chief of State Philippe Pétain in 1940, it was to be Henry-Haye’s “first public proclamation” since his appointment. The tone on campus had been and continued to be antagonistic. The DTH editorial column, titled “Carolina’s Free Speech Continues,” asked that

. . . students who are antagonistic to the ambassador and what he stands for, refrain from showing him anything but the strictest courtesy throughout his address and the open forum. Carolina’s tradition of freedom of expression is too old now to be violated by one night’s rudeness.

Two thousand people attended the speech. There were signs of apprehension during the day, but Henry-Haye’s primary talking point was publicizing the need for aid for the French people, a topic he discussed the previous day with President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull. When asked a confrontational question by a “loquacious” student—”everyone knows the glory of France, but how do you explain Pétain’s alliance with Hitler?”—during an open forum in Graham Memorial after his speech, the audience was “immediately aroused to loud comments and mixed approval and disapproval.” To end the “disorder,” the ambassador took to the microphone and declared, “The answer is too easy. Your comments are not true.”

The United Press account of Henry-Haye’s speech noted his call for a release of French funds frozen by the United States in order to purchase food and clothing for the French living in regions occupied by Germany who were “threatened to perish from starvation,” and for 1.5 million French prisoners. Roosevelt, for his part on that Armistice Day, spoke at Arlington Cemetery, alluding to the current war in Europe while reminding his audience of the reasons America entered into the European War in 1917. Roosevelt quoted the highly decorated World War I soldier Alvin “Sergeant” York: “The thing [people questioning America’s involvement in Word War I] forget is that liberty and freedom and democracy are so very precious that you do not fight to win them once and stop. Liberty and freedom and democracy are prizes awarded only to those peoples who fight to win them and then keep fighting eternally to hold them.”

During the fall semester of 1941, the University of North Carolina’s student-run Carolina Political Union (CPU) had thrice tried to bring Nye to campus, each thwarted by his senatorial duties negating their plans. Nye’s outspoken isolationist views aroused “constant bitter attacks by both opposing forces” in Washington D. C., leading “observers on the campus to doubt the wisdom of promoting additional ‘hatred spreading material.'”

On November 13, five days before Nye’s visit, a DTH headline noted that “Verbal Onslaughts” had been prepared for Nye by campus organizations, and that opposition to Nye was anticipated to “manifest itself vigorously.” Several professors and students were unwilling to have the campus serve as a platform for “bigotry and hatred.” Nye was seen as the “backbone of Congressional opposition to New Deal measures” and as unwilling to “disassociate himself with the ‘fascist elements of the America First committee.'” On that same day, Congress passed legislation that amended the Neutrality Act, permitting U. S. merchant ships to enter war zones.

Nye had been to UNC once before on March 17, 1937, also as a guest of the CPU. His talk was titled, “Preparedness for Peace.” The Daily Tar Heel characterized Nye as a “progressive Republican.” He was an advocate for American neutrality in the burgeoning European War, “to guide us and to make it less easy to be drawn into other people’s wars as has been the case in the past.” Among his points, Nye referred to an amendment then under consideration that “says that when the question of participation in a foreign war arises in this country, the question shall be decided by the people in a duly qualified referendum.” Nye was referring to an amendment to the Neutrality Act of 1935, which evolved during hearings of the Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry” which he chaired and became known as the “Nye Committee.” President Roosevelt led an effort to amend the act, passing The Neutrality Act of 1939 in November that repealed the previous law. Roosevelt and others continued to chip away at the act for the next two years.

Nye’s November 1941 trip to Chapel Hill was one of many he undertook throughout the country sponsored by the America First Committee, a movement to counter the efforts to repeal the Neutrality Act. The America First Committee formed during September 1940, growing out of a student group formed at Yale University. It formally announced its existence on September 4, comprised mostly of midwestern business and political leaders, with headquarters in Chicago. Its financial support came mostly from the conservative wing of noninterventionists. America First Committee’s tenets were:

- keep America out of foreign wars;

- preserve and extend democracy at home;

- keep American naval convoys and merchant ships on the western side of the Atlantic Ocean;

- build a defense for American shores; and

- give humanitarian aid to people in occupied countries.

Nye’s involvement The America First Committee took the form of speeches, ramping up his activity during the summer and autumn of 1941. Nye and the committee’s efforts, however, could not hold sway. On October 9, Roosevelt once again urged Congress to repeal the Neutrality Act. On October 29th, Nye delivered a major address on the Senate floor against the president’s call. Two days later the Germans torpedoed the American destroyer USS Reuben James. It was the first loss of an American military ship. As a result, on November 13 the United States House of Representatives narrowly approved, by a 212-194 vote, a revision to the Neutrality Act of 1939. That same day, The Daily Tar Heel wrote again about Nye’s upcoming visit to campus. An article in The Statesville Daily Record on November 14 also announced Nye’s appearance in Memorial Hall, in which the head of the Carolina Political Union, Ridley Whitaker, said the CPU invited Nye “because regardless of how we may feel about his views, we must recognize the fact that he definitely represents a viewpoint.”

American political milestones and European military events continued to unfold. Roosevelt signed the repeal legislation on November 17, the day before Nye’s speech in Chapel Hill. Nonetheless, as The Daily Tar Heel headline had predicted, Nye faced a jam-packed auditorium with an audience that listened to “the fiery Dakotan on tenterhooks.” After Nye concluded, attendees released “alternating waves of boos, cheers, and hisses.” The following morning, The Daily Tar Heel headlines read, “Stormy Verbal Onslaught” and “Spontaneous Outbursts Threaten Real Disorder.” During his speech, the senator “vigorously maintained that ‘propaganda of the most criminal order has been practiced and lack of frankness by American leaders and downright deception have brought the United States to the brink of war.” After his uninterrupted speech, audience members “flung questions at the rostrum in quick, violent succession.”

Just three weeks later, all the contentious debate became moot. The America First Committee held its last meeting in Pittsburgh on 7 December 1941—as Japan simultaneously bombed Pearl Harbor.

For more on Senator Gerald P. Nye, see Wayne S. Cole’s Senator Gerald P. Nye and American Foreign Relations, published by the University of Minnesota Press in 1962.

A priceless gem for only ten bucks

Today, October 27th, UNC head football coach Larry Fedora leads his 2018 Tar Heels into historic Scott Stadium for a continuation of “the South’s Oldest Rivalry.” This game between the University of North Carolina and the University of Virginia marks the 123rd meeting between the two old rivals. Over the years, since the first meeting between the two in 1892, Carolina has won sixty-four times while UVA has won fifty-four; four games ended in a tie. Of the fifty times Carolina has played UVA on the road, the game in 1948 not only provided Carolina with a highly significant win, it also provided an interesting sidebar story. Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard takes a look back at the game in Scott Stadium on November 27, 1948 between the Tar Heels and the Cavaliers.

Arguably the best UNC football team was the 1948 squad that finished the season undefeated and ranked third in the Associated Press poll. The ’48 Tar Heels started off the season at home with a historic win over the University of Texas, 34 to 7. (Many old-time Tar Heels still like to talk about this game.)

The weekend following the Texas win, Charlie Justice had his best day as a Tar Heel down in Georgia with a win over the Bulldogs. Then came wins over Wake Forest, NC State, LSU, and Tennessee. A tie with William & Mary on November 6th was the only blemish on the ‘48 schedule. Following wins over Maryland and Duke, it was time to close out the historic season—a season that had seen Carolina ranked number one for the first and only time.

With bowl talk in the air, Head Coach Carl Snavely took his team into Scott Stadium for that finale. An overflow crowd of 26,000+ turned out on November 27, 1948, a day that could have very easily been called “Charlie Justice Day.” Here’s why:

- He got off runs of twenty-two and eight yards in the initial Carolina touchdown drive.

- He passed thirty-nine yards to receiver Art Weiner for the second Tar Heel score.

- He cut off left guard on a delayed spinner and outran the field to cross the Virginia goal eighty yards away.

- He passed thirty-one yards to end Bob Cox for Carolina’s fourth touchdown.

- He returned a UVA punt, in a straight line, fifty yards for Carolina’s final touchdown of the day.

In summary: Justice carried the ball fifteen times for a net total of 159 yards—that’s almost 11 yards per carry. He completed four of seven passes for 87 yards. He returned two punts for sixty-six yards. He punted five times for a 40.8 yards per punt average. And oh yes, he intercepted a Virginia pass, had a 49-yard touchdown pass called back as well as a 21-yard run. Needless to say, Carolina won the game 34 to 12 and went on to play in the 1949 Sugar Bowl.

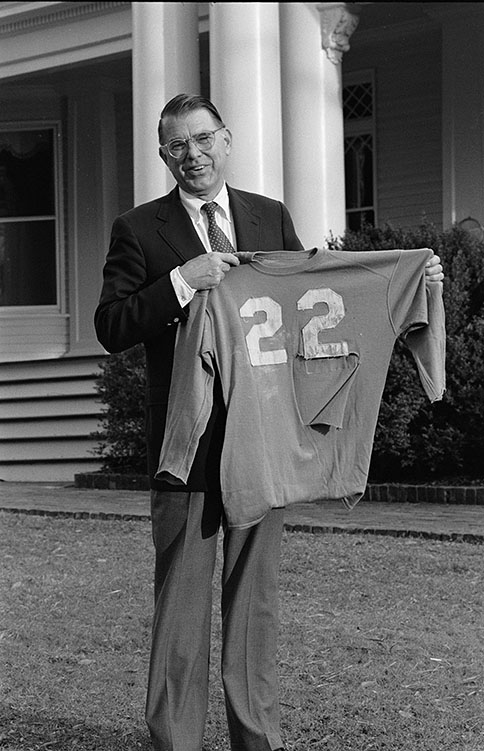

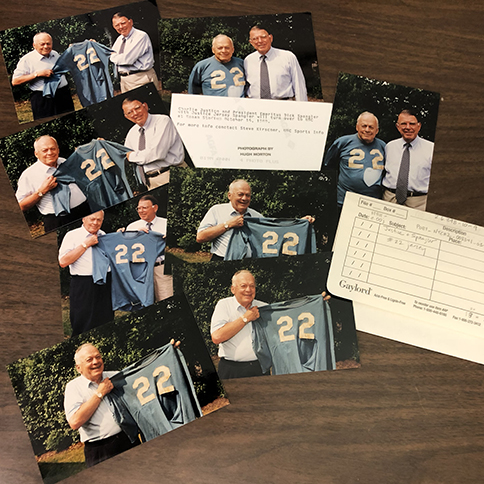

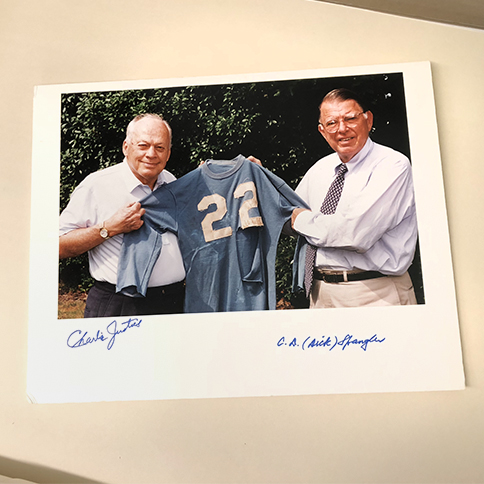

Among those 26,000+ fans in Scott Stadium that afternoon was an eleventh grade student at Woodberry Forest, a prep school in Madison, Virginia. His name, Clemmie Dixon Spangler, Jr. from Charlotte, North Carolina. Spangler, along with several of his school buddies, had made the trip over to Charlottesville for the game. (Clemmie Dixon Spangler, Jr. would become known as C.D. Spangler, Jr. and would lead the University of North Carolina system from 1986 until 1997.)

On one of those great Charlie Justice plays mentioned above, Justice’s #22 jersey was torn. He came over to the Carolina sideline where equipment manager, “Sarge” Keller, quickly got out a new one . . . tossing the torn one over behind the bench into an equipment trunk. In a 1996 interview with A.J Carr of Raleigh’s News & Observer, Spangler described the 1948 Charlottesville scene:

“Charlie was a hero of mine. It was one of his greatest college games. On one play, a linebacker grabbed him, but he twisted away as he often did, ran another 10-15 yards and his jersey was torn.”

“He came over, the trainer helped him put on another and they put the torn one in the trunk. I said: ‘That old jersey would be nice to have.’”

After the game, Spangler got the attention of a Carolina cheerleader and explained that he wanted the Justice jersey. He then offered the cheerleader ten dollars to go and get the jersey out of the trunk. The deal was completed and as Spangler walked out of the stadium, some Carolina fans offered him one hundred dollars. Spangler said, “No deal.”

He displayed the jersey on the wall while in high school and after graduation he kept it in a “safe place.”

“I wouldn’t take anything for it,” Spangler continued. “It’s a piece of history that meant something to me.”

“My mother offered to wash it and sew it. But I said we would not wash it, that we’d keep the lime marks and grass stains and leave it torn.”

“(Charlie Justice) is very symbolic of someone who did well, was a hero and he lived a really good life. He lived up to all expectations and has been a fine representative for North Carolina,” Spangler added as he closed the interview.

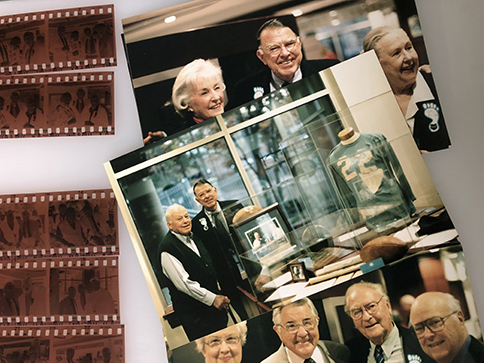

Spangler kept the prized memento for more than fifty years. Then, on November 18, 1989, during halftime of the Carolina–Duke game, he presented the jersey to then UNC Athletic Director Dick Baddour. It is now on display in the Charlie Justice Hall of Honor at the Kenan Football Center.

Morton also used the images in his slides shows, saying: “…the only university president who freely admits to bribery and stealing.”

On April 30, 1984, the Charlotte chapter of the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation staged a Charlie Justice Celebrity Roast and one of the roasters was Justice’s dear friend, teammate, and business partner Art Weiner. One of Weiner’s roast stories went something like this:

We knew that Charlie was competing with SMU’s great All America Doak Walker for the 1948 Heisman Memorial Trophy. When we read in the papers that Walker had a jersey torn up during one his games, we decided, in the huddle, to tear up one of Charlie’s . . . just to make things look equal. But on November 27, 1948, the tear was for real and C.D. Spangler, Jr. got a “Priceless Gem for Only 10 Bucks.”

Mack Brown’s return to Kenan Stadium

Last month, on August 11, 2018, former UNC head football coach Mack Brown revisited Chapel Hill and Kenan Stadium, where he had roamed the sidelines for ten seasons from 1988 through the 1997. The occasion for Brown’s recent return was a celebratory dinner with about fifty Tar Heels from his UNC days, held in the stadium’s Blue Zone, in honor of his selection into the College Football Hall of Fame. The hall announced its 2018 College Football Hall of Fame Class announced back in January, and will hold its induction ceremony on December 4 in New York City.

Brown’s August visit was not first time back to Chapel Hill after his final UNC football season. Morton Collection volunteer Jack Hilliard looks back to September 14, 2002—a visit by Brown that many Tar Heel fans still recall.

The headline in the Saturday, September 14, 2002 edition of the Greensboro News & Record read “Tar Heels hope to catch Texas off guard again.” Sports writer Larry Keech recounted the famous Carolina–Texas game from 1948 when the Tar Heels beat the Longhorns 34 to 7. Keech interviewed Tar Heel All-America Art Weiner and he recalled that day in September of 1948 when he and teammate Charlie Justice made UNC history. Keech closed his story by saying, “If history is to repeat, it will be up to UNC quarterback Darian Durant and receiver Sam Aiken to do their best Justice and Weiner impersonations.”

When Texas head coach Mack Brown and his nationally ranked #3 Texas Longhorns took the field shortly before 8:00 p.m. on Saturday, September 14, 2002, a few boos were heard from the Tar Heel faithful in the Kenan crowd of 60,500—the second largest in Kenan to date. I remember my disappointment at those boos. I chose to believe they were directed at a Tar Heel opponent, not at Coach Brown. It was estimated that there were 5,000 Texas fans in the sold-out crowd.

By the end of the first quarter, and trailing 10 to 0, the chances of that “repeat-history” seemed to be getting farther away. Carolina finally scored in the second quarter but trailed 24 to 7 at the half. That “repeat-history” was now . . . history. There was just too much Texas. Each team scored in the third quarter, but Texas poured it on with 21 points in the fourth. The final score was 52 to 21, Texas.

Following the win, Coach Brown hugged his players and looked toward those Texas fans as he held up the famous “Hook ‘em Horns” sign. The Texas band then played “The Eyes of Texas.” The Tar Heel hype for this game by now was forgotten. Texas was ranked #3 for a reason. They were that good.

Following the Mack Brown–John Bunting handshake at midfield, Coach Brown walked into the atrium of the old Kenan Field House at Kenan Stadium, a room in which he was totally familiar. He was set to address the media.

“I’ve never seen a team play that hard down 31 to 14. The crowd was in it, it was an unbelievable atmosphere. For myself, I’m really proud that North Carolina football is in John Bunting’s hands and moving forward.

“I was impressed with the crowd. I’m proud to be a part of the two biggest in school history. I’m just on the wrong side in one of them . . . . There was way too much talk about me coming back here. . . . We had our struggles and I’m proud of what we did here.”

Mack Brown’s position in Tar Heel history is secure with ACC Coach of the Year honors in 1996, three ten-win-seasons, and a number four national ranking (Coaches’ Poll) for the 11-1 1997 team.

Brown would go on to lead the Longhorns for eleven more seasons, winning the National Championship in 2005. You can see why he will be inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in December.

Epilog

During his most recent campus visit, Coach Brown talked with the 2018 Tar Heel football team and told them it is a “privilege” to play in a historic and winsome venue like Kenen Memorial Stadium. He then added that he was pulling for them each Saturday from his ESPN studio vantage point where he is a network analyst each weekend during football season.