With the 2018 football season kickoff tomorrow on the west coast against the University of California, Berkeley, many Tar Heel fans are ready for their annual rite of autumn. An important part of that rite is fan participation—cheering, it’s called. And no one in Carolina history cheered like the rotund man from Farmville, the unofficial UNC cheerleader they called Tarzan. He was not only famous on the UNC campus. Tarzan was a familiar face and voice at Duke as well as other schools across North Carolina. A View to Hugh awakens from its summer doldrums to the beat of Hugh Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard, who takes a look at the life and times of Lath Morriss.

Author’s Note: In researching this post, I found numerous spellings of the main character’s name—from Lathe to Lath, and from Morris to Morriss. In a Daily Tar Heel story published on December 12, 1946, the man himself says his name is Lath Morriss. So that’s what I will go with throughout this post.

When Duke University’s Blue Devils traveled to Pasadena, California for the 25th annual Rose Bowl game on January 2, 1939, the opponent was the University of Southern California. Many Duke fans across North Carolina were not able to make the long trip to California for the game, so they listened to sportscaster Bill Stern’s coast-to-coast broadcast on NBC radio. Not only did they get Stern’s play-by-play account of the famous game, but another well known voice was heard during the broadcast. It was that of Lath Morriss cheering on the opposite side of the field from Stern’s broadcast booth.

Lath Morriss was born in Brenham, Texas on February 15, 1904 and spent his early years in and around that small town. He had a love for the game of football. He played fullback on his high school team and quarterback on his college team.

After college, Lath took a job in Port Arthur, Texas with the Smith Construction Company, which had recently acquired a contract to build a highway between Farmville and Wilson in North Carolina. When the construction company completed the road project, Morriss stayed in North Carolina and took a job in Farmville with the A.C. Monk Tobacco Company. He was often seen at football games at Duke and attended his first game in Kenan Stadium in 1927.

His unusual voice often became a distraction in the cheering sections. During a Duke – Colgate game in Duke Stadium, university security asked him to leave. The Associated Press, which covered the game, reported that Morriss had been evicted. Students who were seated near him that September day, however, said he just went across the field and started cheering for Colgate.

Morriss soon found a “home” in Chapel Hill on football Saturdays. He became known as the “Screaming Eagle” in The Daily Tar Heel but the students called him Tarzan. In a 1935 interview in The Daily Tar Heel, Lath said, “I reckon you might call a voice like mine somewhat unusual, but I believe it has its good points.”

UNC’s 1937 season opener against the University of South Carolina ended in a 13-to-13 draw. The Daily Tar Heel blamed Tarzan’s absence for the tie. S. R. Rolfe writing in the Sunday, September 26 issue said, “For the first time in memory . . . Tarzan was not at a Carolina ball game. That may be the reason for the tie. The team probably missed his ‘15 rahs’ and shrill yell.”

At the UNC pep rally on Fetzer Field for the 1946 Duke game, Tarzan was one of the featured speakers, along with another famous Carolina Cheerleader, Kay Kyser. A portion of the rally was broadcast on WPTF radio. Tarzan was in rare form the next day when Duke came into Kenan Stadium for the thirty-third meeting between the two old rivals. He led Rameses, the Carolina mascot, around the stadium to the delight of the photographers covering the game, as Carolina won 22 to 7 to cap off the first Duke–Carolina game of the “Golden Era” in Chapel Hill.

In a game billed as the “1947 Sugar Bowl Rematch,” the Tar Heels took on the Georgia Bulldogs in Chapel Hill on September 27. Following a 0-to-0 first half, Morriss led the Tar Heels back onto the field for the second half. With megaphone in hand; he shouted “Go, go, go, go . . . Care-lina.” The students shouted back, “Go, go, go, go . . . Tarzan.” Carolina came back in the second half to win 14 to 7 to the delight of the Tar Heel fans among the 43,000 in Kenan Memorial Stadium.

Tarzan’s picture was often displayed in The Daily Tar Heel, and in UNC’s yearbook, The Yackerty Yack (both the 1947 and 1949 editions). Even the magazine The State carried a cover photograph of the man from Farmville in its November 22, 1947 taken by photographer Bugs Barringer of Rocky Mount.

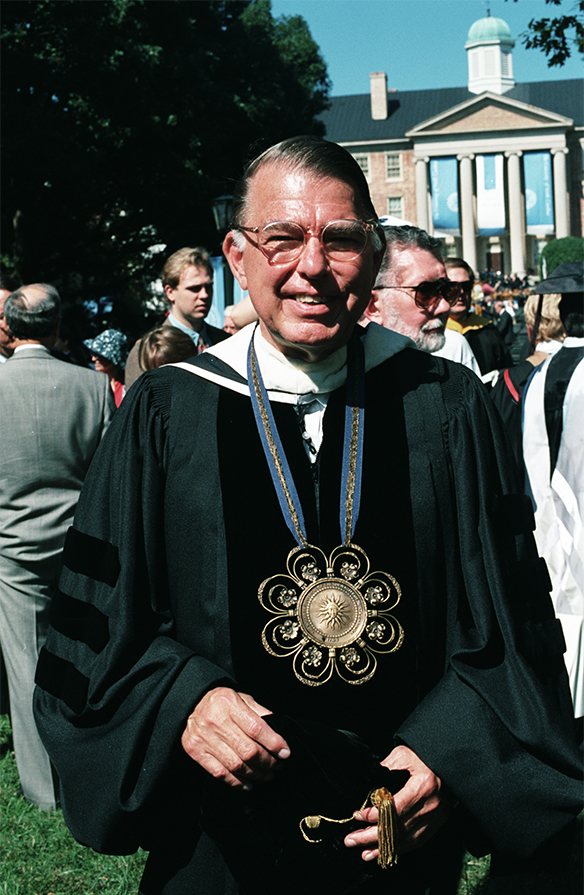

The year 1949 brought to a close the “Golden Era” of Tar Heel sports, but the Lath Morriss story continued in Chapel Hill. When The Chapel Hill Newspaper printed its sixth “Town & Gown” edition in August of 1975, it included a picture of Tarzan. And in 2016 when author and historian Lee Pace published his book Football in a Forest: The Life and Times of Kenan Memorial Stadium, he featured the following Hugh Morton image of Tarzan on pages 134-135.

The sad news from Farmville on July 30, 1962 told of the passing of Lath Morriss. He was 58-years-old.