Belated Happy New Year!

For the past year or so, it has been really difficult for me to write blog posts for A View to Hugh on a regular basis. Thank goodness for Jack Hilliard’s continued interest in writing for the blog! If you are a regular reader, you might be wondering why it has been relatively quiet here. You might even be thinking that, eleven years after this blog’s debut in November 2007, there isn’t much work being done with the Morton collection. If fact, just the opposite is true. I worked extensively with the Morton collection during 2018. In honor of what would be Hugh Morton’s 98th birthday today, let me share with you what I have been doing to extend the life of his photographic negatives.

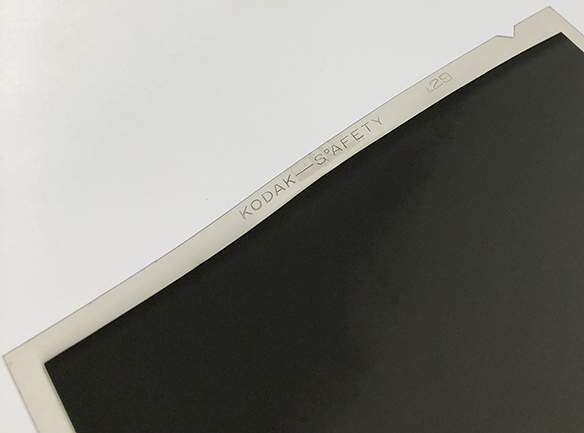

Morton’s film negatives and color transparencies dating from the late 1930s through the early 1960s are physically made of cellulose acetate film stock. The common name for these various acetate negatives is “safety film” because it replaced cellulose nitrate film stock, which is highly flammable. Many brands of film from that time period have the word SAFETY imprinted onto the edge of the film. Kodak issued its first safety film in 1926, but they became more common in the marketplace by the early to mid 1930s. They coexisted for several years with their cellulose nitrate brethren. Adding SAFETY to the sheet films’ edges distinguished them from their predecessor films made using cellulose nitrate, which then began to have the word NITRATE on their edges.

A keen eye will notice in the negative seen above that its edge has a slight wave. If you follow the links to the Wikipedia entries in the previous paragraph about these film bases, you may read more about how they deteriorate. For acetate films, basically, the negative begins to distort as the cellulose acetate base layer begins to break down, eventually causing its base to separate from the emulsion layer. The first stage of deterioration is a symmetrical curling of the film edges, meaning the curls are the same on opposite sides of the negative. This can go undetected if the collection is not used or inspected routinely.

Typically one’s nose is the first to detect that deterioration has begun. When the chemical composition of the cellulose acetate degrades to a certain level, the film emits the smell of vinegar—acetic acid. The next stage of deterioration is an asymmetrical warpage of the negative: where the curling is “upward” on one edge, it is “downward” on the opposite edge. Often, but not always, small bubbles will appear. Finally, the emulsion layer and the film base separate from each other.

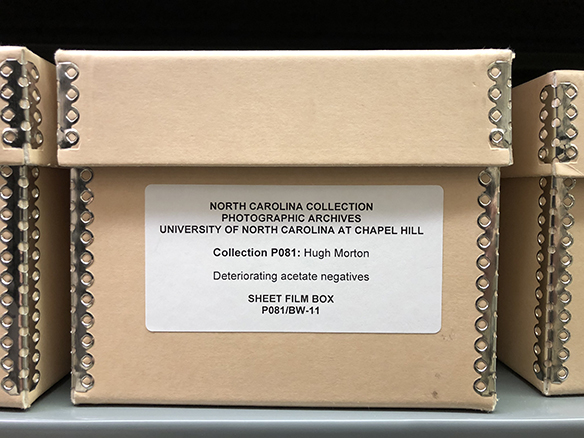

We detected that some acetate negative deterioration had already taken place in the Morton collection before it arrived at Wilson Library, although the problem was not widespread. We removed those negatives that were already deteriorated and those that exhibited the early stages of deterioration into a separate box during archival processing. We did that in order to isolate the bad from the good, because the deterioration process is autocatalytic and thus can cause nearby good negatives to deteriorate. If you look in the Morton collection finding aid, you will see several entries with the phrase “removed to Sheet Film Box P081/BW-11 due to acetate deterioration.”

Storing negatives in a warm and/or humid environment exacerbates the deterioration process. A cool, dry environment slows down the process; only storage at zero degrees Fahrenheit, however, will impede the process.

Acetate deterioration became known to film manufacturing industry in the late 1940s. Manufacturers developed a replacement made from polyester during the early 1960s. Polyester films are remarkable stable.

The traditional method to preserve images on nitrate and acetate film negatives has been to make duplicate film copies using the interpositive method. An unexposed polyester film negative is placed in direct contact, emulsion to emulsion, to the acetate or nitrate negative, then properly exposed to light and chemically developed using archival film processing techniques. A negative film stock exposed to a photographic negative, produces a positive, which is then used to expose it to another sheet of unexposed film to make a duplicate negative—hence the word interpositive.

Vendors who make preservation duplicates using film today are rare and the cost is prohibitive because film and processing chemistry are no longer readily available. As you probably guessed, the duplication method has been replaced by digital technology. But it was not until September 2016 that an agreed upon standard—the Federal Agencies Digital Guidelines Initiative (FADGI)—determined specifications deemed acceptable for preservation digitization. That high level of preservation digitization is called FADGI 4-star.

In mid November 2016, the North Carolina Collection received a significant donation from the Ellis and Rosa McDonald Fund for Excellence to provide continued support of the Hugh Morton collection preservation project. I embarked on a pilot project with Chicago Albumen Works using a representative sample of negatives of different formats (3×4-inch negatives, 4x5s, 35mm, as examples). After completing the pilot project, I decided to focus on Morton’s earliest work, typically 3×4 negatives before he routinely used 4×5 starting in the early 1950s. I then moved to the 4×5 negatives made until the transition from acetate film to polyester film stocks in the early 1960s.

For both formats I needed to determine the negatives’ condition and—because we couldn’t possibly digitize every negative in the collection—the importance of their subject matter and the image quality of the negatives. To keep track of selections sent to the vendor, I created a spreadsheet that also helped me to standardize the file names for the scans to be typed by the vendor during production. In summary, Chicago Albumen Works digitized nearly 2,950 negatives at FADGI 4-star quality.

All that represents a significant amount of work that kept me from putting together blog posts. One post did emerge from the process when I discovered the negatives of Gerald P. Nye’s visit to UNC, and another post about Alton Lennon is waiting in the wings. This post is getting a bit long, however, so I’ll stop here and save additional details about the preservation digitization project for a future peek “Behind the Scenes.”

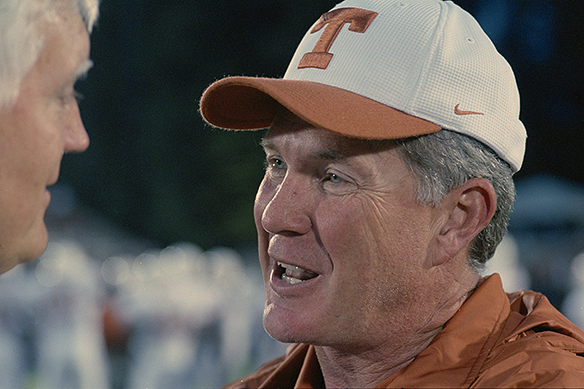

A call to the Hall for coach Mack Brown

Editor’s Note

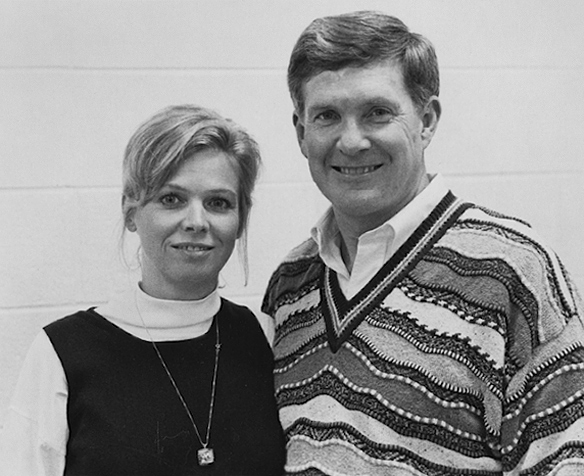

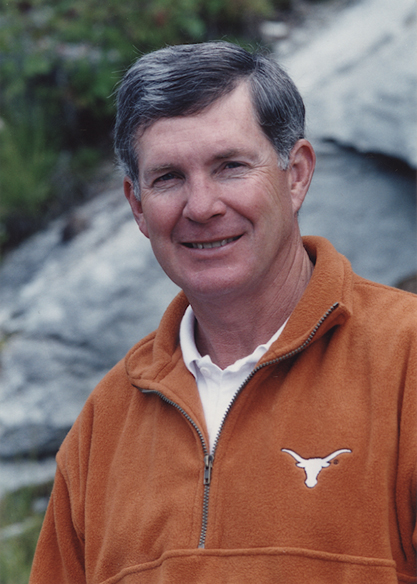

This post is a follow-up to the post, “Mack Brown’s Return to Kenan Stadium” published on September 11 earlier this year. As we were preparing today’s post honoring Mack Brown for his induction into the National Football Foundation’s College Football Hall of Fame, UNC and Chancellor Carol Folt and Athletic Director Bubba Cunningham announced during a noontime press conference on November 27 that Brown will return to coaching duties for Carolina. Brown then stepped to the podium and addressed the gathered media. “Sally and I love North Carolina, we love this University and we are thrilled to be back. The best part of coaching is the players—building relationships, building confidence, and ultimately seeing them build success on and off the field. We can’t to wait to meet our current student-athletes and reconnect with friends, alumni and fellow Tar Heel coaches.”

On December 4, 2018, former Head Football Coach Mack Brown will become the twelfth UNC Tar Heel and the twenty-second Texas Longhorn to be inducted into the National Football Foundation’s College Football Hall of Fame. The dinner ceremony from 8:30 p.m. until 11:00 p.m. EST can be watched via a livestream on ESPN3. Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard takes a look at Brown’s thirty-year head coaching career.

When it’s all over, your career will not be judged by the money you made or the championships you won. It will be measured by the lives you touched. And that is why we coach. —Mack Brown in One Heartbeat (2001), page 173.

It was November 18, 1989. Tar Heel head football coach Mack Brown had just suffered one of the worst defeats of his entire coaching career at the end of a second 1-and-10 season. But Brown felt a personal obligation to come back up on the Kenan Stadium field because the Raycom TV crew wanted one more seasoning-ending interview. By the time Brown finished his locker room and media conference duties, the late November sun was setting far beyond the west end of the historic stadium, and most all of the 46,000 fans who had filled the stands earlier had headed home. About midway through the interview, Brown was distracted by cheering from the far end zone. He turned and looked. What he saw was unbelievable. Duke head coach Steve Spurrier had come out of the visitor dressing room and assembled his team around the still-lighted scoreboard, which read 41 to 0. The Blue Devil photographers were snapping away. Brown paused for several seconds, and then said, “We’ll remember that.” Coach Brown never lost again to Duke University during his entire coaching career.

Mack Brown began his successful head-coaching career at Appalachian State in 1983, leading the Mountaineers to a 6-5 record—their first winning season in four years. Then following a successful season as the offensive coordinator at Oklahoma under Hall of Fame coach Barry Switzer, he became the head coach and athletic director at Tulane in 1985, where he led the Green Wave to a 6-6 record in his final season in 1987 and earned a trip to the Independence Bowl. It was only the fifth bowl appearance for Tulane since 1940.

Following his time at Tulane, Brown was hired by UNC Athletic Director John Swofford, just in time for the big 100th anniversary of Carolina football during the 1988 season. But those first two seasons at Carolina were dreadful, showing only two wins and twenty losses. With the 1990 season, however, things were turned around and during the next eight seasons, Brown added sixty-seven additional wins—tied for the second most victories in school history. The team was bowl-bound every year beginning in 1992, including a win in the 1993 Peach Bowl. The Atlantic Coast Conference named Brown ACC Coach of the Year in 1996. Brown led Carolina to three ten-win seasons, while the team finished in the top twenty-five four times, including tenth in 1996 and fourth in 1997.

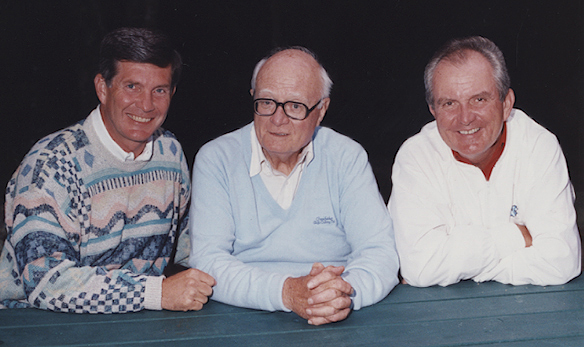

During his time in Chapel Hill, Brown became good friends with Hugh Morton and visited often at Grandfather Mountain. In fact, Brown built a home there. And he was instrumental in the construction of another home . . . this one in Chapel Hill and it goes by the name Frank H. Kenan Football Center, completed in 1997.

It was Saturday, September 13, 1997. Carolina was hosting a late afternoon game with Stanford. Coach Brown and one of his assistants, Cleve Bryant, who had been an assistant at Texas, were on the Kenan field watching the Tar Heels warm up, when on the stadium public address system, announcer Dave Lohse started giving some scores from the early games. He then gave a halftime score: UCLA 38, Texas 0.

Said Bryant, “that can’t be right.” Coach Brown didn’t pay much attention; he was intent on the game at hand. About two hours later, up in the Kenan press box, UNC Sports Information Director Rick Brewer handed some final scores to announcer Lohse. As he did so, he said. “I think we just lost our football coach.” Brewer was fully aware of Brown’s admiration for Texas football history and tradition. Lohse then read the final score: UCLA 66, Texas 3. When Bryant heard that score, he turned to Brown and said, “I wouldn’t want to be in Austin, Texas tonight.” From that moment, for the next eighty-four days, speculation was rampant: would Mack Brown leave a place he dearly loved, for an opportunity of a lifetime? Finally, on Wednesday, December 3, 1997 it became official: Mack Brown would be the new head football coach at the University of Texas.

Coach Brown’s time in Austin was legendary. His 158 career Texas wins are second only to Hall of Fame Coach Darrell Royal in Longhorn history. During the 2005 season, Brown guided Texas to its first national championship in 35 years after defeating Southern California in the 2006 Rose Bowl in one of the greatest games in college football history. In 2009, Brown became Big 12 Coach of the Year while winning his second conference title. He would become a two-time National Coach of the Year and won more than 10 games in 9 consecutive seasons. He also won 10 bowl games while in Texas.

Over his 30-year-coaching-career, Brown coached 37 First Team All-Americas, 6 Academic All-Americas, 110 first team all-conference selections and 11 conference Players of the Year. He also coached 2 College Football Hall of Famers in Tar Heel Dre Bly and Heisman Trophy winner Ricky Williams at Texas; and 4 National Football Foundation National Scholar-Athletes, including Campbell Trophy winners Sam Acho and Dallas Griffin also at Texas. Brown posted 20 consecutive winning seasons from 1990 to 2009 and his 225 wins from 1990 to 2013 were the most among Football Bowl Subdivision coaches during those years. He has a total of 244 wins—tenth most by a coach in FBS history. He led teams to 22 bowl games.

Among his personal honors, Brown is a member of the Texas Longhorns Hall of Honor. He is also enshrined in the Rose Bowl, State of Texas Sports, State of Tennessee Sports and Holiday Bowl halls of fame. Until November 27th, he served as a college football studio and game analyst at ESPN and served as a special assistant at Texas.

Mack Brown and wife, Sally, have helped raise millions of dollars for children’s charities, and Mack was recently named the Football Bowl Association’s Champions Award recipient for 2019. He was also honored in the Blue Zone at Kenan Stadium on Saturday, August 12, 2018 for his upcoming December 4th induction into the College Football Hall of Fame.

Toward the end of the Blue Zone ceremony, Brown came to the podium and acknowledged many Tar Heels in the audience. There was John Swofford, the Carolina athletic director who hired him and then after those 1-10 seasons gave him a contract extension. There were former assistant coaches Darrell Moody and Dan Brooks, who had been so very important in those early recruiting efforts. And there were former Tar Heels from eras before Brown arrived as a 36-year-old head coach. “You guys were the ones who made this place special and gave us something we could sell,” Brown said.

There were about fifty Tar Heels present from Brown’s time in Chapel Hill. Also in attendance was UNC 1970 All-America Don McCauley who is also a College Football Hall of Famer, Class of 2001.

“I’m not going into the Hall of Fame, I am presenting you all in the Hall of Fame. Football is the ultimate team sport, and no one person is ever the one that wins a football game. When I take that oath in December and I say ‘thank you’ to the Hall of Fame, I’m doing it for each one of you. Your name in my mind will be in the Hall of Fame forever.” Carolina Athletic Director Bubba Cunningham added, “Brown’s legacy wasn’t just about winning; it was about developing young men to be successful after football.”

Part of the celebration was a panel discussion with several former Tar Heel players talking about Brown and his Chapel Hill legacy. One of those players was fellow Hall of Famer Dre Bly who spoke of getting a sideline dressing down in his first game as a Tar Heel in the 1996 season opener against Clemson, a 45-0 Tar Heel landslide.

“The play was on our sidelines, a ball into the flat. I made a big hit. I was high-stepping and celebrating. Coach Brown grabbed my facemask and had a few select words for me. He said, ‘We don’t do that here.’ I knew then and there, I had to remain humble. I learned the importance of being humble. I saw the big picture, I understood what’s important. We had a very talented team. I couldn’t be the one to mess it up. I needed to remain humble, and I’ve used that my whole life.” (I wish the UNC head football coaches that followed Brown would have maintained that same high standard.)

I believe it’s safe to say, whether you view it as Burnt Orange or Carolina Blue, Brown’s legacy is secure, and on Tuesday night, December 4, 2018, he will stand for the administration of his induction as the citation of his accomplishments is read—this year in the Trianon Ballroom of the New York Hilton Midtown, just as coach Darrell Royal and Bobby Layne of Texas and coach Carl Snavely and Charlie Justice of Carolina stood years before in the Grand Ballroom of the historic Waldorf-Astoria—as William Mack Brown will be honored as a new member of the College Football Hall of Fame. Coach Brown will make the official response on behalf of the 2018 College Football Hall of Fame Class.

A golden celebration

Prolog:

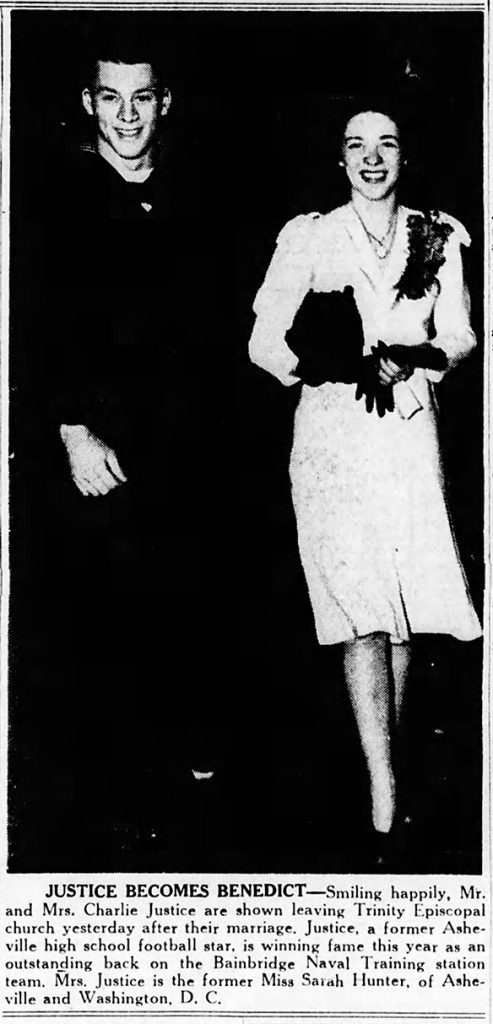

Ten days after future UNC football legend Charlie Justice led his undefeated Bainbridge Naval Training Station football team to a 46-to-0 win over the University of Maryland, he went on a well-deserved leave. At the same time, Sarah Alice Hunter took a brief leave from her job at the Naval Observatory in Washington, D. C. The two headed back home to Asheville, North Carolina where they were married at Trinity Episcopal Church.

During the next 59 years, 10 months, and 23 days, Charlie Justice would be interviewed numerous times. During most of those interviews, he would, at some point, say “the best thing I ever did was to ask Sarah to marry me.”

Intro:

They played the 80th meeting between Carolina and Duke on November 26, 1993—a chilly, gray Friday morning—at 11 o’clock. My guess is that ABC-TV wanted it played on that day at that time. As it turned out, that was a good thing because the game ended about 2:30 PM, in plenty of time for a very special celebration in “the living room of the University” across campus.

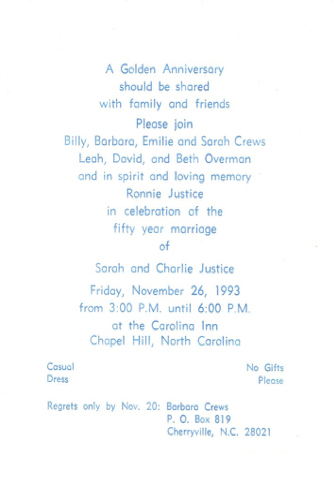

Today, on the day Charlie and Sarah Justice would have celebrated their 75th wedding anniversary, Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard looks back 25 years at their 50th celebration.

A few minutes after Carolina beat Duke 38 to 24 in the 1993 edition of their annual in-state rivalry, (thanks to freshman running back Leon Johnson’s 142-yard-and-4-touchdown day), many of us headed across campus to the historic Carolina Inn, where family and friends of the special couple were gathering. Although Charlie and Sarah Justice’s fiftieth wedding anniversary was actually on November 23rd, game day on the 26th seemed like a good time to celebrate the storybook event of November 23rd, 1943.

In addition to celebrating the Justice’s fiftieth anniversary, the event also honored the memory of their son Charles Ronald (Ronnie), who had passed away on Friday, June 11, 1993 at their home in Flat Rock, North Carolina.

This is how the Justice’s chose to invite their guests:

There were family members, teammates, friends, and fans in attendance.

The Carolina Inn ballroom provided the perfect backdrop for the elegant event and the many guests surrounded a large buffet table with roast beef, salmon, fruits, and cheeses. The centerpiece was a large ice sculpture depicting a locomotive celebrating Charlie’s football career when he was called “Choo Choo.”

At the right side of the room was a video player and large screen where highlights of Charlie and Sarah’s fifty years together were shown. I had the honor of producing that video presentation which was narrated by North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame broadcaster Charlie Harville.

Following a family toast by Barbara (Justice) Crews, Charlie and Sarah’s daughter, head football coach Mack Brown added his congratulations and then offered an additional toast. He then spoke of the importance of Carolina’s football history and heritage. After Brown concluded his words about Carolina’s Golden Age during the late 1940s, Justice stepped forward and thanked the coach for restoring football respectability “for my University.”

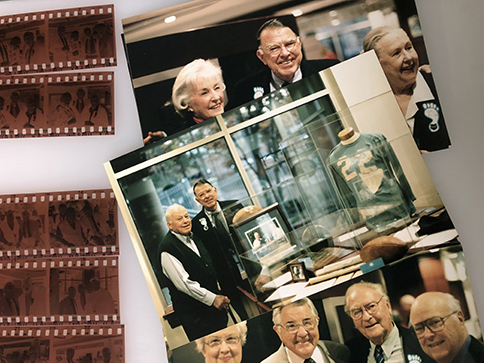

During the entire celebration, photographer Hugh Morton was there documenting every phase of the event: from a group shot of the Justice team mates to a funny shot of Charlie and Sarah holding up special tee shirts prepared for the party, a shot that appeared in the February, 1994 edition of The University Alumni Report newspaper on page 34.

So, on this day, November 23, 2018, I choose to believe that Charlie and Sarah Justice are once again celebrating their storybook life together on their 75th wedding anniversary. Joining the celebration is son Ronnie, and just as he was 25 years ago, Hugh Morton is there with camera in hand.

Fiery "America First" Dakotan takes on Tar Heels

The controversy between isolationists and interventionists became an unusually rugged affair with no holds barred on either side. . . . The name-calling, mud-slinging, and smearing on both sides made the foreign policy debate a poor place for the sensitive or fainthearted. Each side welcomed almost any chance to discredit the opposition.

—Wayne S. Cole in Gerald P. Nye and American Foreign Relations

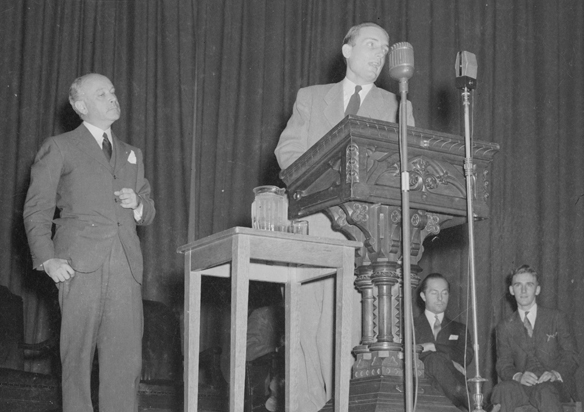

It was Armistice Day—Tuesday, 11 November 1941— and United States Senator Gerald P. Nye’s speech at the University of North Carolina, announced to the student body that day—was still a week away. Despite the frivolity of Sadie Hawkins Day events during the weekend, peace was not on the horizon. In the opening sentence of his front-page article of The Daily Tar Heel, writer Paul Komisaruk predicted the nature of the upcoming event:

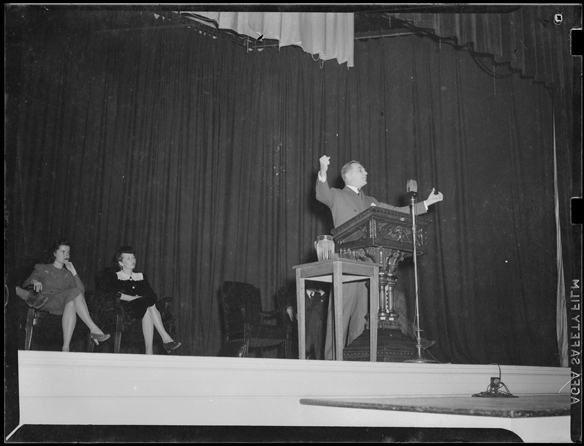

National politics and policies erupt from the Memorial hall rostrum next Tuesday night as North Dakota’s Old Guard isolationist, Senator Gerald P. Nye, attacks New Deal measures before a Chapel Hill audience under the auspices of the CPU [Carolina Political Union].

On that same November 11th evening, Vichy France‘s ambassador to the United States, Gaston Henry-Haye, was the International Relations Club (IRC) speaker at Memorial Hall. Appointed by Chief of State Philippe Pétain in 1940, it was to be Henry-Haye’s “first public proclamation” since his appointment. The tone on campus had been and continued to be antagonistic. The DTH editorial column, titled “Carolina’s Free Speech Continues,” asked that

. . . students who are antagonistic to the ambassador and what he stands for, refrain from showing him anything but the strictest courtesy throughout his address and the open forum. Carolina’s tradition of freedom of expression is too old now to be violated by one night’s rudeness.

Two thousand people attended the speech. There were signs of apprehension during the day, but Henry-Haye’s primary talking point was publicizing the need for aid for the French people, a topic he discussed the previous day with President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull. When asked a confrontational question by a “loquacious” student—”everyone knows the glory of France, but how do you explain Pétain’s alliance with Hitler?”—during an open forum in Graham Memorial after his speech, the audience was “immediately aroused to loud comments and mixed approval and disapproval.” To end the “disorder,” the ambassador took to the microphone and declared, “The answer is too easy. Your comments are not true.”

The United Press account of Henry-Haye’s speech noted his call for a release of French funds frozen by the United States in order to purchase food and clothing for the French living in regions occupied by Germany who were “threatened to perish from starvation,” and for 1.5 million French prisoners. Roosevelt, for his part on that Armistice Day, spoke at Arlington Cemetery, alluding to the current war in Europe while reminding his audience of the reasons America entered into the European War in 1917. Roosevelt quoted the highly decorated World War I soldier Alvin “Sergeant” York: “The thing [people questioning America’s involvement in Word War I] forget is that liberty and freedom and democracy are so very precious that you do not fight to win them once and stop. Liberty and freedom and democracy are prizes awarded only to those peoples who fight to win them and then keep fighting eternally to hold them.”

During the fall semester of 1941, the University of North Carolina’s student-run Carolina Political Union (CPU) had thrice tried to bring Nye to campus, each thwarted by his senatorial duties negating their plans. Nye’s outspoken isolationist views aroused “constant bitter attacks by both opposing forces” in Washington D. C., leading “observers on the campus to doubt the wisdom of promoting additional ‘hatred spreading material.'”

On November 13, five days before Nye’s visit, a DTH headline noted that “Verbal Onslaughts” had been prepared for Nye by campus organizations, and that opposition to Nye was anticipated to “manifest itself vigorously.” Several professors and students were unwilling to have the campus serve as a platform for “bigotry and hatred.” Nye was seen as the “backbone of Congressional opposition to New Deal measures” and as unwilling to “disassociate himself with the ‘fascist elements of the America First committee.'” On that same day, Congress passed legislation that amended the Neutrality Act, permitting U. S. merchant ships to enter war zones.

Nye had been to UNC once before on March 17, 1937, also as a guest of the CPU. His talk was titled, “Preparedness for Peace.” The Daily Tar Heel characterized Nye as a “progressive Republican.” He was an advocate for American neutrality in the burgeoning European War, “to guide us and to make it less easy to be drawn into other people’s wars as has been the case in the past.” Among his points, Nye referred to an amendment then under consideration that “says that when the question of participation in a foreign war arises in this country, the question shall be decided by the people in a duly qualified referendum.” Nye was referring to an amendment to the Neutrality Act of 1935, which evolved during hearings of the Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry” which he chaired and became known as the “Nye Committee.” President Roosevelt led an effort to amend the act, passing The Neutrality Act of 1939 in November that repealed the previous law. Roosevelt and others continued to chip away at the act for the next two years.

Nye’s November 1941 trip to Chapel Hill was one of many he undertook throughout the country sponsored by the America First Committee, a movement to counter the efforts to repeal the Neutrality Act. The America First Committee formed during September 1940, growing out of a student group formed at Yale University. It formally announced its existence on September 4, comprised mostly of midwestern business and political leaders, with headquarters in Chicago. Its financial support came mostly from the conservative wing of noninterventionists. America First Committee’s tenets were:

- keep America out of foreign wars;

- preserve and extend democracy at home;

- keep American naval convoys and merchant ships on the western side of the Atlantic Ocean;

- build a defense for American shores; and

- give humanitarian aid to people in occupied countries.

Nye’s involvement The America First Committee took the form of speeches, ramping up his activity during the summer and autumn of 1941. Nye and the committee’s efforts, however, could not hold sway. On October 9, Roosevelt once again urged Congress to repeal the Neutrality Act. On October 29th, Nye delivered a major address on the Senate floor against the president’s call. Two days later the Germans torpedoed the American destroyer USS Reuben James. It was the first loss of an American military ship. As a result, on November 13 the United States House of Representatives narrowly approved, by a 212-194 vote, a revision to the Neutrality Act of 1939. That same day, The Daily Tar Heel wrote again about Nye’s upcoming visit to campus. An article in The Statesville Daily Record on November 14 also announced Nye’s appearance in Memorial Hall, in which the head of the Carolina Political Union, Ridley Whitaker, said the CPU invited Nye “because regardless of how we may feel about his views, we must recognize the fact that he definitely represents a viewpoint.”

American political milestones and European military events continued to unfold. Roosevelt signed the repeal legislation on November 17, the day before Nye’s speech in Chapel Hill. Nonetheless, as The Daily Tar Heel headline had predicted, Nye faced a jam-packed auditorium with an audience that listened to “the fiery Dakotan on tenterhooks.” After Nye concluded, attendees released “alternating waves of boos, cheers, and hisses.” The following morning, The Daily Tar Heel headlines read, “Stormy Verbal Onslaught” and “Spontaneous Outbursts Threaten Real Disorder.” During his speech, the senator “vigorously maintained that ‘propaganda of the most criminal order has been practiced and lack of frankness by American leaders and downright deception have brought the United States to the brink of war.” After his uninterrupted speech, audience members “flung questions at the rostrum in quick, violent succession.”

Just three weeks later, all the contentious debate became moot. The America First Committee held its last meeting in Pittsburgh on 7 December 1941—as Japan simultaneously bombed Pearl Harbor.

For more on Senator Gerald P. Nye, see Wayne S. Cole’s Senator Gerald P. Nye and American Foreign Relations, published by the University of Minnesota Press in 1962.

A priceless gem for only ten bucks

Today, October 27th, UNC head football coach Larry Fedora leads his 2018 Tar Heels into historic Scott Stadium for a continuation of “the South’s Oldest Rivalry.” This game between the University of North Carolina and the University of Virginia marks the 123rd meeting between the two old rivals. Over the years, since the first meeting between the two in 1892, Carolina has won sixty-four times while UVA has won fifty-four; four games ended in a tie. Of the fifty times Carolina has played UVA on the road, the game in 1948 not only provided Carolina with a highly significant win, it also provided an interesting sidebar story. Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard takes a look back at the game in Scott Stadium on November 27, 1948 between the Tar Heels and the Cavaliers.

Arguably the best UNC football team was the 1948 squad that finished the season undefeated and ranked third in the Associated Press poll. The ’48 Tar Heels started off the season at home with a historic win over the University of Texas, 34 to 7. (Many old-time Tar Heels still like to talk about this game.)

The weekend following the Texas win, Charlie Justice had his best day as a Tar Heel down in Georgia with a win over the Bulldogs. Then came wins over Wake Forest, NC State, LSU, and Tennessee. A tie with William & Mary on November 6th was the only blemish on the ‘48 schedule. Following wins over Maryland and Duke, it was time to close out the historic season—a season that had seen Carolina ranked number one for the first and only time.

With bowl talk in the air, Head Coach Carl Snavely took his team into Scott Stadium for that finale. An overflow crowd of 26,000+ turned out on November 27, 1948, a day that could have very easily been called “Charlie Justice Day.” Here’s why:

- He got off runs of twenty-two and eight yards in the initial Carolina touchdown drive.

- He passed thirty-nine yards to receiver Art Weiner for the second Tar Heel score.

- He cut off left guard on a delayed spinner and outran the field to cross the Virginia goal eighty yards away.

- He passed thirty-one yards to end Bob Cox for Carolina’s fourth touchdown.

- He returned a UVA punt, in a straight line, fifty yards for Carolina’s final touchdown of the day.

In summary: Justice carried the ball fifteen times for a net total of 159 yards—that’s almost 11 yards per carry. He completed four of seven passes for 87 yards. He returned two punts for sixty-six yards. He punted five times for a 40.8 yards per punt average. And oh yes, he intercepted a Virginia pass, had a 49-yard touchdown pass called back as well as a 21-yard run. Needless to say, Carolina won the game 34 to 12 and went on to play in the 1949 Sugar Bowl.

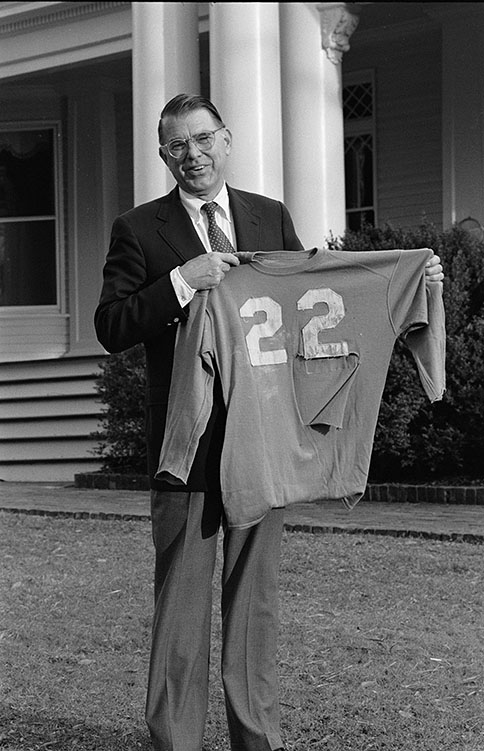

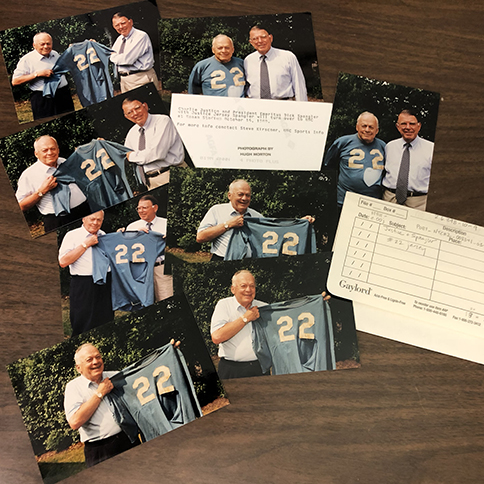

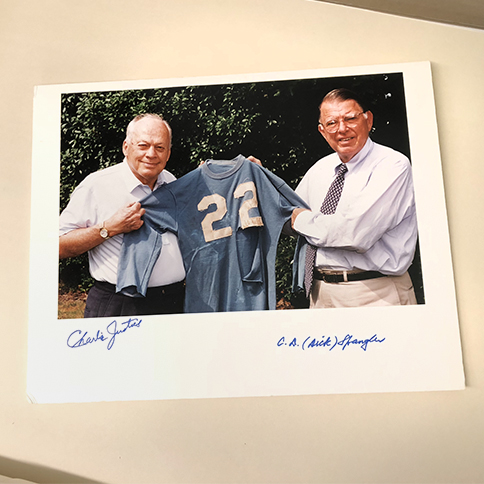

Among those 26,000+ fans in Scott Stadium that afternoon was an eleventh grade student at Woodberry Forest, a prep school in Madison, Virginia. His name, Clemmie Dixon Spangler, Jr. from Charlotte, North Carolina. Spangler, along with several of his school buddies, had made the trip over to Charlottesville for the game. (Clemmie Dixon Spangler, Jr. would become known as C.D. Spangler, Jr. and would lead the University of North Carolina system from 1986 until 1997.)

On one of those great Charlie Justice plays mentioned above, Justice’s #22 jersey was torn. He came over to the Carolina sideline where equipment manager, “Sarge” Keller, quickly got out a new one . . . tossing the torn one over behind the bench into an equipment trunk. In a 1996 interview with A.J Carr of Raleigh’s News & Observer, Spangler described the 1948 Charlottesville scene:

“Charlie was a hero of mine. It was one of his greatest college games. On one play, a linebacker grabbed him, but he twisted away as he often did, ran another 10-15 yards and his jersey was torn.”

“He came over, the trainer helped him put on another and they put the torn one in the trunk. I said: ‘That old jersey would be nice to have.’”

After the game, Spangler got the attention of a Carolina cheerleader and explained that he wanted the Justice jersey. He then offered the cheerleader ten dollars to go and get the jersey out of the trunk. The deal was completed and as Spangler walked out of the stadium, some Carolina fans offered him one hundred dollars. Spangler said, “No deal.”

He displayed the jersey on the wall while in high school and after graduation he kept it in a “safe place.”

“I wouldn’t take anything for it,” Spangler continued. “It’s a piece of history that meant something to me.”

“My mother offered to wash it and sew it. But I said we would not wash it, that we’d keep the lime marks and grass stains and leave it torn.”

“(Charlie Justice) is very symbolic of someone who did well, was a hero and he lived a really good life. He lived up to all expectations and has been a fine representative for North Carolina,” Spangler added as he closed the interview.

Spangler kept the prized memento for more than fifty years. Then, on November 18, 1989, during halftime of the Carolina–Duke game, he presented the jersey to then UNC Athletic Director Dick Baddour. It is now on display in the Charlie Justice Hall of Honor at the Kenan Football Center.

Morton also used the images in his slides shows, saying: “…the only university president who freely admits to bribery and stealing.”

On April 30, 1984, the Charlotte chapter of the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation staged a Charlie Justice Celebrity Roast and one of the roasters was Justice’s dear friend, teammate, and business partner Art Weiner. One of Weiner’s roast stories went something like this:

We knew that Charlie was competing with SMU’s great All America Doak Walker for the 1948 Heisman Memorial Trophy. When we read in the papers that Walker had a jersey torn up during one his games, we decided, in the huddle, to tear up one of Charlie’s . . . just to make things look equal. But on November 27, 1948, the tear was for real and C.D. Spangler, Jr. got a “Priceless Gem for Only 10 Bucks.”

Mack Brown’s return to Kenan Stadium

Last month, on August 11, 2018, former UNC head football coach Mack Brown revisited Chapel Hill and Kenan Stadium, where he had roamed the sidelines for ten seasons from 1988 through the 1997. The occasion for Brown’s recent return was a celebratory dinner with about fifty Tar Heels from his UNC days, held in the stadium’s Blue Zone, in honor of his selection into the College Football Hall of Fame. The hall announced its 2018 College Football Hall of Fame Class announced back in January, and will hold its induction ceremony on December 4 in New York City.

Brown’s August visit was not first time back to Chapel Hill after his final UNC football season. Morton Collection volunteer Jack Hilliard looks back to September 14, 2002—a visit by Brown that many Tar Heel fans still recall.

The headline in the Saturday, September 14, 2002 edition of the Greensboro News & Record read “Tar Heels hope to catch Texas off guard again.” Sports writer Larry Keech recounted the famous Carolina–Texas game from 1948 when the Tar Heels beat the Longhorns 34 to 7. Keech interviewed Tar Heel All-America Art Weiner and he recalled that day in September of 1948 when he and teammate Charlie Justice made UNC history. Keech closed his story by saying, “If history is to repeat, it will be up to UNC quarterback Darian Durant and receiver Sam Aiken to do their best Justice and Weiner impersonations.”

When Texas head coach Mack Brown and his nationally ranked #3 Texas Longhorns took the field shortly before 8:00 p.m. on Saturday, September 14, 2002, a few boos were heard from the Tar Heel faithful in the Kenan crowd of 60,500—the second largest in Kenan to date. I remember my disappointment at those boos. I chose to believe they were directed at a Tar Heel opponent, not at Coach Brown. It was estimated that there were 5,000 Texas fans in the sold-out crowd.

By the end of the first quarter, and trailing 10 to 0, the chances of that “repeat-history” seemed to be getting farther away. Carolina finally scored in the second quarter but trailed 24 to 7 at the half. That “repeat-history” was now . . . history. There was just too much Texas. Each team scored in the third quarter, but Texas poured it on with 21 points in the fourth. The final score was 52 to 21, Texas.

Following the win, Coach Brown hugged his players and looked toward those Texas fans as he held up the famous “Hook ‘em Horns” sign. The Texas band then played “The Eyes of Texas.” The Tar Heel hype for this game by now was forgotten. Texas was ranked #3 for a reason. They were that good.

Following the Mack Brown–John Bunting handshake at midfield, Coach Brown walked into the atrium of the old Kenan Field House at Kenan Stadium, a room in which he was totally familiar. He was set to address the media.

“I’ve never seen a team play that hard down 31 to 14. The crowd was in it, it was an unbelievable atmosphere. For myself, I’m really proud that North Carolina football is in John Bunting’s hands and moving forward.

“I was impressed with the crowd. I’m proud to be a part of the two biggest in school history. I’m just on the wrong side in one of them . . . . There was way too much talk about me coming back here. . . . We had our struggles and I’m proud of what we did here.”

Mack Brown’s position in Tar Heel history is secure with ACC Coach of the Year honors in 1996, three ten-win-seasons, and a number four national ranking (Coaches’ Poll) for the 11-1 1997 team.

Brown would go on to lead the Longhorns for eleven more seasons, winning the National Championship in 2005. You can see why he will be inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in December.

Epilog

During his most recent campus visit, Coach Brown talked with the 2018 Tar Heel football team and told them it is a “privilege” to play in a historic and winsome venue like Kenen Memorial Stadium. He then added that he was pulling for them each Saturday from his ESPN studio vantage point where he is a network analyst each weekend during football season.

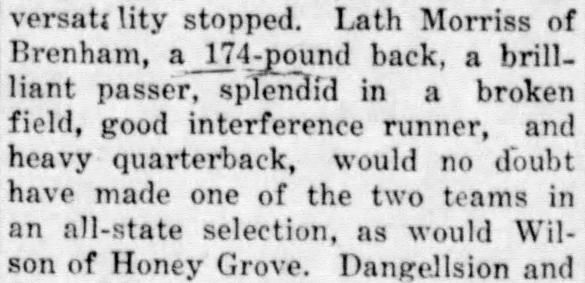

Lath Morriss: the cheerleader they called Tarzan

With the 2018 football season kickoff tomorrow on the west coast against the University of California, Berkeley, many Tar Heel fans are ready for their annual rite of autumn. An important part of that rite is fan participation—cheering, it’s called. And no one in Carolina history cheered like the rotund man from Farmville, the unofficial UNC cheerleader they called Tarzan. He was not only famous on the UNC campus. Tarzan was a familiar face and voice at Duke as well as other schools across North Carolina. A View to Hugh awakens from its summer doldrums to the beat of Hugh Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard, who takes a look at the life and times of Lath Morriss.

Author’s Note: In researching this post, I found numerous spellings of the main character’s name—from Lathe to Lath, and from Morris to Morriss. In a Daily Tar Heel story published on December 12, 1946, the man himself says his name is Lath Morriss. So that’s what I will go with throughout this post.

When Duke University’s Blue Devils traveled to Pasadena, California for the 25th annual Rose Bowl game on January 2, 1939, the opponent was the University of Southern California. Many Duke fans across North Carolina were not able to make the long trip to California for the game, so they listened to sportscaster Bill Stern’s coast-to-coast broadcast on NBC radio. Not only did they get Stern’s play-by-play account of the famous game, but another well known voice was heard during the broadcast. It was that of Lath Morriss cheering on the opposite side of the field from Stern’s broadcast booth.

Lath Morriss was born in Brenham, Texas on February 15, 1904 and spent his early years in and around that small town. He had a love for the game of football. He played fullback on his high school team and quarterback on his college team.

After college, Lath took a job in Port Arthur, Texas with the Smith Construction Company, which had recently acquired a contract to build a highway between Farmville and Wilson in North Carolina. When the construction company completed the road project, Morriss stayed in North Carolina and took a job in Farmville with the A.C. Monk Tobacco Company. He was often seen at football games at Duke and attended his first game in Kenan Stadium in 1927.

His unusual voice often became a distraction in the cheering sections. During a Duke – Colgate game in Duke Stadium, university security asked him to leave. The Associated Press, which covered the game, reported that Morriss had been evicted. Students who were seated near him that September day, however, said he just went across the field and started cheering for Colgate.

Morriss soon found a “home” in Chapel Hill on football Saturdays. He became known as the “Screaming Eagle” in The Daily Tar Heel but the students called him Tarzan. In a 1935 interview in The Daily Tar Heel, Lath said, “I reckon you might call a voice like mine somewhat unusual, but I believe it has its good points.”

UNC’s 1937 season opener against the University of South Carolina ended in a 13-to-13 draw. The Daily Tar Heel blamed Tarzan’s absence for the tie. S. R. Rolfe writing in the Sunday, September 26 issue said, “For the first time in memory . . . Tarzan was not at a Carolina ball game. That may be the reason for the tie. The team probably missed his ‘15 rahs’ and shrill yell.”

At the UNC pep rally on Fetzer Field for the 1946 Duke game, Tarzan was one of the featured speakers, along with another famous Carolina Cheerleader, Kay Kyser. A portion of the rally was broadcast on WPTF radio. Tarzan was in rare form the next day when Duke came into Kenan Stadium for the thirty-third meeting between the two old rivals. He led Rameses, the Carolina mascot, around the stadium to the delight of the photographers covering the game, as Carolina won 22 to 7 to cap off the first Duke–Carolina game of the “Golden Era” in Chapel Hill.

In a game billed as the “1947 Sugar Bowl Rematch,” the Tar Heels took on the Georgia Bulldogs in Chapel Hill on September 27. Following a 0-to-0 first half, Morriss led the Tar Heels back onto the field for the second half. With megaphone in hand; he shouted “Go, go, go, go . . . Care-lina.” The students shouted back, “Go, go, go, go . . . Tarzan.” Carolina came back in the second half to win 14 to 7 to the delight of the Tar Heel fans among the 43,000 in Kenan Memorial Stadium.

Tarzan’s picture was often displayed in The Daily Tar Heel, and in UNC’s yearbook, The Yackerty Yack (both the 1947 and 1949 editions). Even the magazine The State carried a cover photograph of the man from Farmville in its November 22, 1947 taken by photographer Bugs Barringer of Rocky Mount.

The year 1949 brought to a close the “Golden Era” of Tar Heel sports, but the Lath Morriss story continued in Chapel Hill. When The Chapel Hill Newspaper printed its sixth “Town & Gown” edition in August of 1975, it included a picture of Tarzan. And in 2016 when author and historian Lee Pace published his book Football in a Forest: The Life and Times of Kenan Memorial Stadium, he featured the following Hugh Morton image of Tarzan on pages 134-135.

The sad news from Farmville on July 30, 1962 told of the passing of Lath Morriss. He was 58-years-old.

C.D. Spangler Jr: 1932—2018

“What we are trying to do, after all, is something we North Carolinians believe we are good at: inspiring our citizens to become the best that they can be. Our mission for the future may have a familiar ring, to make the weak students strong and the strong students great.”

— C. D. Spangler Jr., inaugural address, October 17, 1986

Sunday, July 23, 2018 saw the passing of C.D. Spangler Jr., former president of the University of North Carolina. Clemmie Dixon Spangler Jr. was born April 5, 1932 in Charlotte, North Carolina. Among his many accomplishments, Spangler served as president of the University of North Carolina system from 1986, succeeding William Friday, to 1997.

Jack Hilliard shared with me this morning a story Spangler liked to share about Bill Friday. Spangler was traveling in Gaston County when he saw the highway sign for Dallas, North Carolina and then remembered that Dallas was the hometown of Dr. Friday. He decided to take the exit and see if he could find the Friday home. When he arrived in Dallas he stopped at a country store where a couple of gentlemen were seated out front. He asked if they knew where the Friday home was. They said, “Oh! Yes, it’s just down the road a bit . . . you can’t miss it.” Spangler then asked if they knew Dr. Friday. “Sure, we knew him. He was a great baseball player; a catcher, and a good one.” After a brief pause, one of the old gentlemen then added, “You know, if he had continued his baseball career, he might have made something of himself.”

Closer to home here at A View to Hugh . . . in 1996, the C. D. Spangler Foundation contributed $335,00 to help create a $500,000 endowed professorship at UNC-Greensboro in honor of Julia Morton, Hugh Morton’s wife, where she graduated Phi Beta Kappa. She served on the UNC Board of Governors for sixteen years.

There are several photographs of C.D. Spangler in the Morton collection, including twenty-six available in the online collection of Morton images.

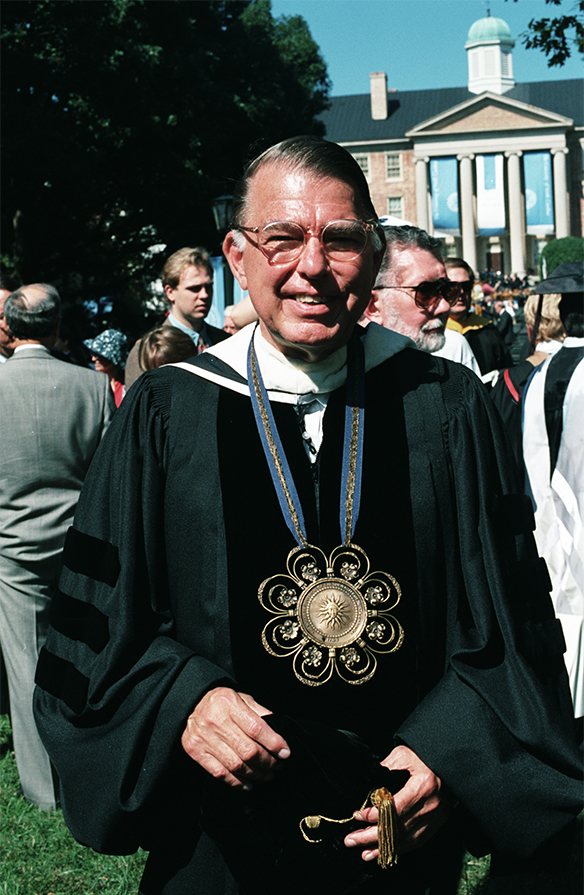

Paul Hardin: UNC’s bicentennial chancellor

Chancellor Paul Hardin was a visionary leader who is remembered in North Carolina and across our nation for his dedication to promoting the life-changing impact and benefits of higher education

— UNC Chancellor Carol L. Folt, July 2017

One year ago today, July 1, 2017, UNC lost a giant: Chancellor Emeritus Paul Hardin III. Hardin led the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill during its bicentennial observance, died at his Chapel Hill home after a courageous battle with ALS, commonly referred to as Lou Gehrig’s disease. He was 86 years old. On this first anniversary of his death, Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard looks back at Chancellor Hardin’s time at UNC and his magnificent bicentennial leadership.

A Phi Beta Kappa from Duke University, Class of 1952, Paul Hardin led three schools—Wofford College, Southern Methodist University, and Drew University—before becoming UNC’s seventh chancellor on July 1, 1988. He was officially installed on October 12 during a University Day installation ceremony, where Hardin told those gathered: “The future belongs to those institutions and persons who command it, not to those who wait passively for it to happen.”

At UNC, Hardin established the Employee Forum, which gave non-academic university employees a greater voice. He was an advocate for UNC-Chapel Hill and campaigned successfully for greater fiscal and management flexibility for the state’s public universities. He aggressively led UNC through some of its most important events. When he stepped down in 1995, Carolina was ready for its third century.

One of those important events was Carolina’s bicentennial observance. On October 11, 1991, he officially launched the largest fund-raising effort in University history—the Bicentennial Campaign for Carolina.

“To command the future this university must compete successfully in the complex and highly competitive world of public higher education,” said Hardin as he announced that $55 million in gifts and pledges had already been raised. The bell in South Building rang out to mark the announcement.

It was October 12, 1793 when the University North Carolina laid the cornerstone for its first building, now named Old East. During the next two centuries, the university went from that single building to one of the nation’s most prestigious public universities. And on October 12, 1993 UNC celebrated that growth in a very special way under Hardin’s leadership.

Bicentennial planning had begun on August 28, 1985 when then Chancellor Chris Fordham sent Richard Cole, dean of the UNC School of Journalism and Mass Communications, a note asking him to chair an “ad hoc committee to assist in planning the forthcoming Bicentennial.” During the next eight years, plans were carefully put into place for the observance. Chancellor Hardin looked upon Carolina’s 200th birthday as an opportunity to “light the way” for Carolina’s future. “Dare to think big and to dream,” he told the numerous planning committees. They did.

A predawn rain fell on the UNC campus on October 12, 1993, the actual 200th birthday of the university, but that didn’t deter any of the planned celebration. As a crowd of 3,000 filed into McCorkle Place for a 10:00 a.m. rededication ceremony of Old East, the sun came out. UNC President C.D. Spangler then stepped to podium.

“I want to thank publicly Chancellor Paul Hardin for the excellent leadership he is giving our university. I feel quite certain that with such strong leadership now and in the future, 200 years from now in 2193 there will be an assemblage of people at this same location again celebrating this wonderful university.”

Following the Distinguished Alumni Awards presentations, President Spangler again came forward—this time to make an unexpected announcement. Holding up a gold pocket watch that had belonged to William Richardson Davie, the university’s founding father, Spangler explained: “Emily Davie Kornfield in her will . . . bequeathed to the University of North Carolina the watch . . . having the letter ‘D’ inscribed on its back. . . Chancellor, I take great pleasure in presenting William Richardson Davie’s watch to you for perpetual care by the University of North Carolina.” Chancellor Hardin accepted the timepiece that is now a part of the North Carolina Collection at Wilson Library.

The University Day celebration continued with the planting of Davie Popular III from a seed of the original tree. Also, 104 two-foot saplings from the original tree were distributed to sixth-graders representing North Carolina’s 100 counties and the Cherokee Indian Reservation. UNC Head Basketball Coach Dean Smith handed out the twigs from a flat-bed truck. The young students took the twigs back to each county for planting.

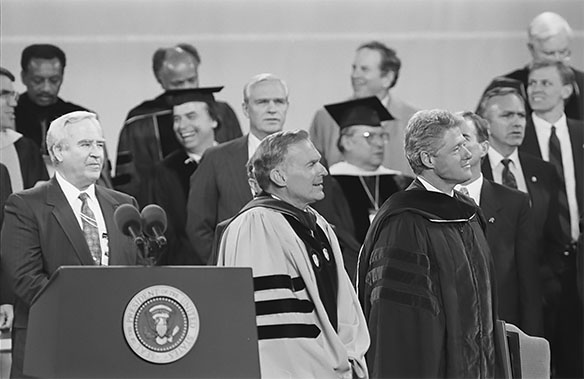

The University Day Bicentennial Observance culminated with a celebration in Kenan Memorial Stadium, with Chancellor Hardin leading the proceedings. And just as he was thirty-two years before when President John F. Kennedy spoke on University Day 1961, photographer Hugh Morton was there to document the proceedings.

The University Day processional led by Faculty Marshal Ron Hyatt preceded the evening’s speakers: The Honorable James B. Hunt, Jr., Governor of North Carolina; Charles Kuralt, North Carolina Hall of Fame journalist; and Dr. William C. Friday, President-Emeritus of UNC. Then at 8:24 p.m., C.D. Spangler introduced William Jefferson Clinton, President of the United States of America. Following Clinton’s thirty-five-minute speech, Chancellor Hardin conferred an honorary degree on the forty-second president.

Then Hardin closed the evening’s proceedings: “Tonight we have rubbed shoulders with history, and we stand with you—Mr. President—facing a future that baffles prediction but whose promise surely exceeds our wildest imaginings. We are profoundly grateful for your message of hope and promise and humbled to share even part of your day alongside matters of vast global consequence. . . May we set as our goal that our nation’s first state university may also be its best.”

Twelve years after Hardin stepped down from his post as Chancellor, in March of 2007, he and his wife, Barbara, joined with then-Chancellor James Moeser and Chancellor Emeritus William Aycock and former Interim Chancellor Bill McCoy for the dedication on south campus of Hardin Hall, a newly built residence hall named in his honor.

Also on hand that day was Dick Richardson, a retired provost and political science professor who chaired the bicentennial observance while Hardin was chancellor. Richardson said of his former boss, “There is no veneer to him. No pretense, no façade of personality to hide the real person. . . . If you scratch deeply beneath the surface of Paul Hardin, you will find exactly what you find on the surface, for this man is solid oak from top to bottom.”

A memorial service was held on Saturday afternoon, July 8, 2017 at University United Methodist Church in Chapel Hill; and on that day the university rang the bell in South Building seven times, to honor Paul Hardin’s role in UNC history as the seventh chancellor. The ringing of the bell is used to mark only the most significant university occasions.

Correction: 2 July 2018

Linked to the correct blog post on William Richardson Davie’s watch on North Carolina Miscellany. The previous link led to a post on Elisha Mitchell’s watch.

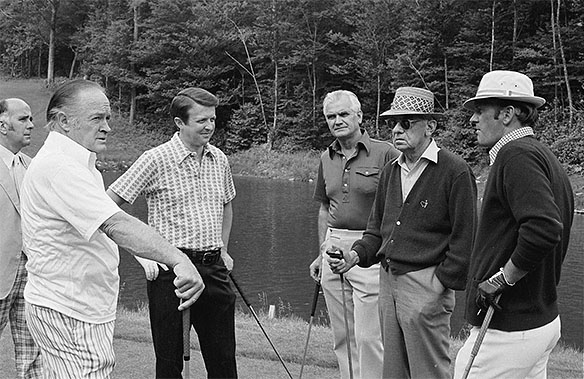

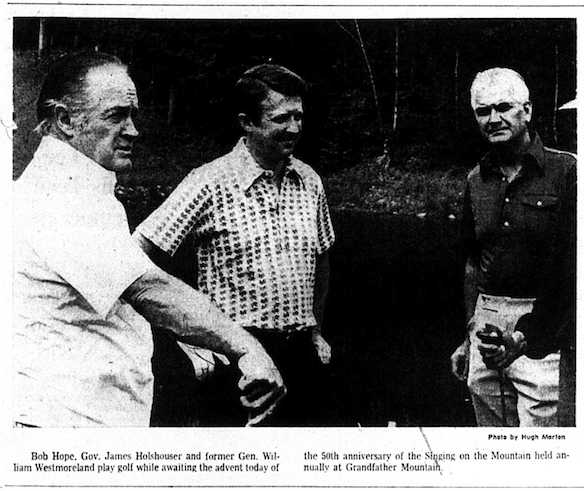

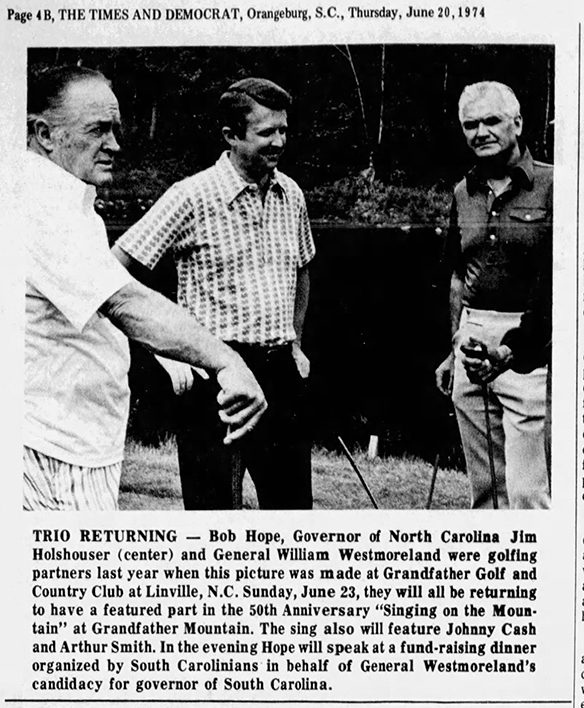

When Hope and Holshouser golfed at Grandfather

Earlier this month, Jack Hilliard wrote a post about the 1974 Singing on the Mountain and sent it to me for publication in time for this year’s Singing on Sunday, June 24. As I began proofing and fact checking the text and looking for images, some of the then-known details about a particular photograph weren’t falling in line, so I decide to do a bit of research to set the matter straight. What evolved is this parallel to Jack’s post. If you are arriving at this post first, it may be better to read his first (linked below).

As I discovered today, while preparing Jack Hilliard’s post about the 1974 Singing on the Mountain, that the above photograph by Hugh Morton was not made in June 1974 as was previously believed. Several newspapers published the photograph in their Sunday editions for June 23, 1974, the day of the Singing. One newspaper was the Greensboro Daily News as seen below. Notice the cropping compared to the full-frame negative above.

While researching Jack’s post, the logistics of Bob Hope traveling back and forth between Asheville and Linville wasn’t making much sense to me. So, I dug into newspapers.com to see if I could find any clues. Yep, another Morton Mystery arose: the same photograph published in The Times and Democrat of Orangeburg, South Carolina had a much more explanatory caption:

Turns out Morton made the photograph a year earlier! Back to newspapers.com to solve this mystery!

According to The Asheville Citizens staff writer Jay Hensley in his June 13, 1973 article titled “Governor Meets King of Quips,” Hugh Morton arranged a golf match to be played on the back nine holes at Grandfather Golf and Country Club on June 12, 1973. Morton paired North Carolina Governor James Holshouser and comedian Bob Hope to play against Clifford Roberts and Robert Kletcke—respectively, the president and golf pro of Augusta National Golf Course.

As cropped in the newspaper, one gets the impression that Hope, Westmoreland, Holshouser, and one other person identified only by a hand holding a golf club made up a foursome before, during, or after playing a round. (As we see from the full image, that hand belongs to Roberts.)

What was the purpose behind the outing? Hensley’s article does not say directly, but he does report the background around it. Holshouser and Hope apparently had played a round of golf on some previous occasion with Vice President Spiro T. Agnew. Hope and his wife Dolores were guests of General Westmoreland at the country club, there for a “short visit.” Westmoreland wanted to offer his guests complete relaxation during their stay, but Hope enjoyed the outing nonetheless. Hope’s wife Dolores, Hugh Morton’s sister Agnes, and Raleigh attorney Camelia Trot played in a group after the men.

Again according to Hensley, Holshouser “broke off from a Tuesday meeting of the Southern Regional Education Board” being held in Hot Springs, Virginia. Linville is a four-and-a-half-hour drive from Hot Springs, so it was quite a break off unless traveling by air.

Westmoreland was nursing an injured right arm, so he didn’t even play. Instead, he “restricted his activities to putting around the golf course.” A caption in a photograph published in the June 15 edition of the newspaper described the group, however, as a fivesome.

Here are two quips Hope offered during the round:

- “Smile and they’ll think we are winning,” he said to Holshouser.

- “I thought this course was named for me until I met you,” he told Clifford Roberts. Roberts was 79 year old at the time, Hope 70.