Mable Hillary and Hazel Dickens, Southern Grassroots Music Tour, 1973/1974. Photo by Cory Foster. call no. PA-20304/1.

Mable Hillary and Hazel Dickens, Southern Grassroots Music Tour, 1973/1974. Photo by Cory Foster. call no. PA-20304/1.

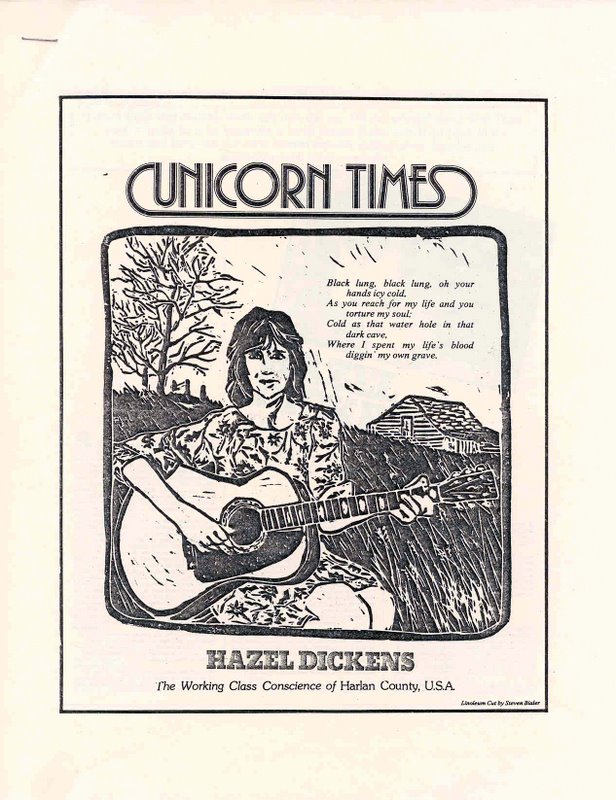

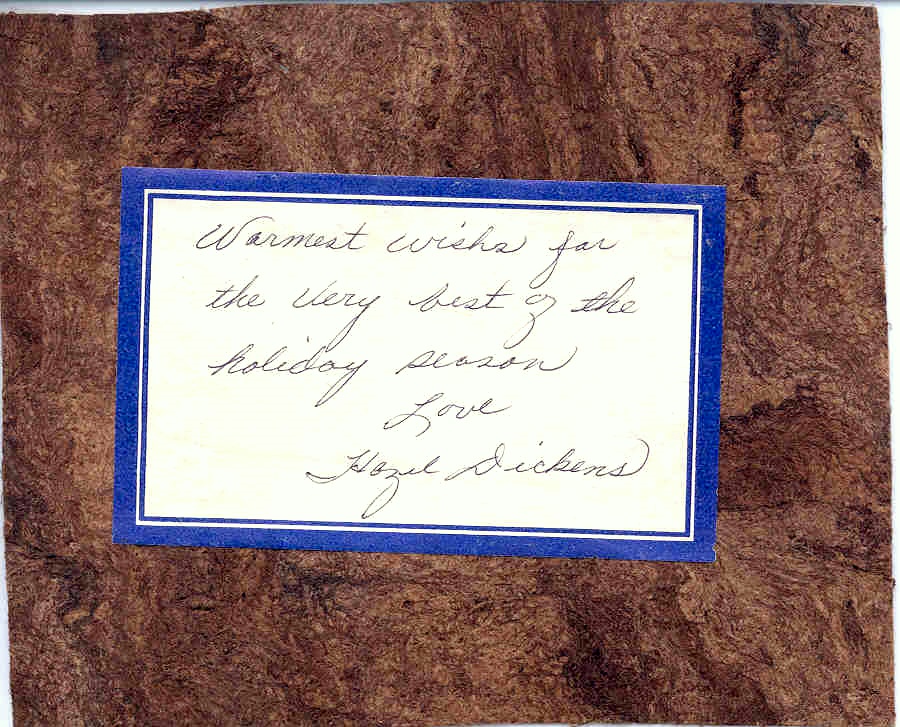

A quick post today featuring an oral history heavy article on Hazel Dickens that originally appeared in the Washington D. C. alternative/underground newspaper, The Unicorn Times, in 1977. See complete article below and previous Hazel Dickens tributes here: part 1 and part 2.

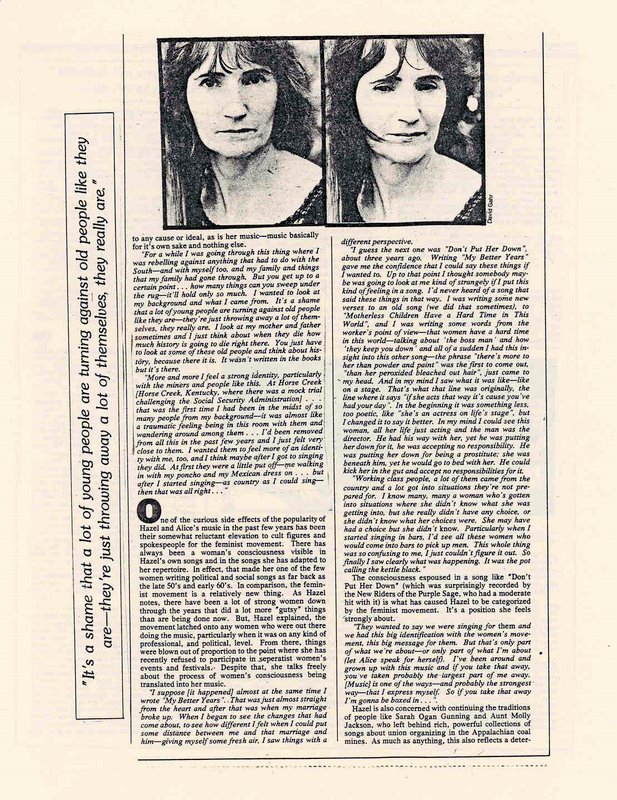

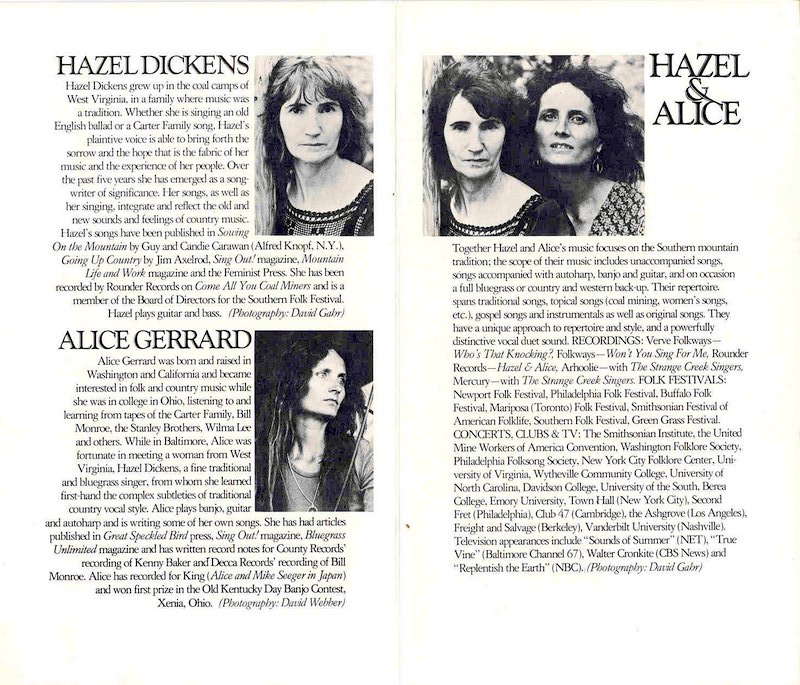

Besides offering a comprehensive biography of her life up until the time it was published in 1977, the Unicorn Times article gives equal, or perhaps, even more space to Hazel’s own voice. Much like the book Dickens would co-write with Bill Malone thirty years later, the article gives Hazel the opportunity to critique her own life story as it had been told by others: folklorists, record companies, and the media. Among the subjects addressed are Dickens meeting and playing music with Mike Seeger in the 1950s, her feelings about her own Southern identity and mountain heritage, her status as a feminist role model, and of course her political activism. Hazel also talks about performance styles, tradition and change in country music, and the frustration that many performers feel when their creative expression is forced into categories.

“There’s so many people that get put down for doing real traditional music. For those people who still have the guts to get out there and do it, it’s a political thing. They’re to be commended for trying to preserve the music. For those people who want to go on to something else, I see nothing wrong with that. It’s part of the freedom to do what you want to do.

For myself, I like to sing that music. Whether I’m singing on or off key, whether I’m even missing some of the chords, when I’m at my best is when I’m belting it out and giving it all I’ve got. It’s something of tme that I can’t put forth if I’m restrained or trying to get everything just right. Some people when they hear country, they think of country-western, but to me it’s traditional, raw…not too pretty a sound to some people because people with a trained ear would be very put off by that sound. The voice may be gravelly, it’s not polished or too stylized. It’s not a smooth style, it’s all feeling and emotion.

When I’m at my best is when I’m singing like that. If I get too involved with what other people are thinking, with trying to sing on pitch or trying to sing the way I know some people would like to hear me sing. I lose it.” [“Hazel Dickens: The Working Class Conscience of Harlan County, U. S. A.,” Unicorn Times, August 1977, by Alice Gerrard, Len Stanley, and Richard Harrington]