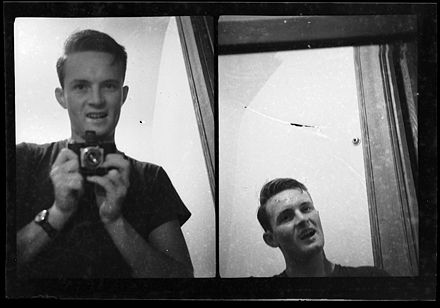

From Elizabeth: Allow me to introduce our summer student assistant, David Meincke, the author of this post. David grew up in the small town of Hebron, Connecticut, received his BA in English from the College of William and Mary in May of 2007, and began the Masters of Library Science program here at UNC’s School of Information and Library Science (“SILS”) this summer. Since he came in with experience digitizing film, slides and photographs, we put him to work at the HR Universal Film Scanner. He surfaced from his cave long enough to write the following. Note: I suspect the images below were taken at “Singing on the Mountain.”

This is my first post on the Hugh Morton blog—up until now my work on the project has mainly been spent in a dark room with a high-powered scanner the size and shape of a Galapagos tortoise. I spend most of my time digitizing film negatives, the majority of them black and white, from various stages of Hugh Morton’s life and career.

I’ve grown accustomed to watching faces, bodies, rivers, lakes, arenas and street corners fly by on the monitor before me. The number of images in the collection is the hundreds of thousands, and it is difficult to retain anything of the image beyond the few seconds it lingers on my screen before it is sealed away on a hard drive somewhere. Occasionally, however, a “golden roll” falls out of the slim acid-free envelope, and it, for some reason, creates such a vivid impression that I have to study, stare, and tell others about it.

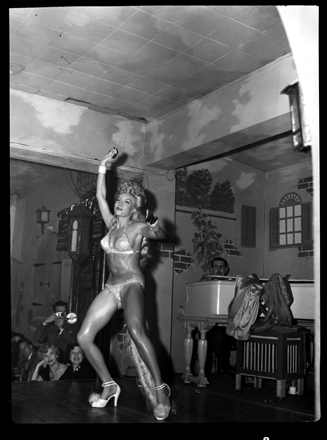

These pictures were taken at an event that seems to be a cross between a religious revival and a country music jamboree: an accordionist, banjo player, and a few guitarists play, while the crowd assembled around them raise their hands in exultation (and in one woman’s case, what appears to be religious ecstasy). I wonder, do any of these faces look familiar to you?

Here a boy stands, surrounded by motherly figures, and only his head is visible amid the confusion of blouses, as if he were coming up for air. Despite the crowd around him, though, he has a serene look, and his face is the only one in sharp focus as he stares into the camera.

The picture that initially caught my attention was the one below, a man with bright sunlight coming in behind him that provides a nice contrast to the picture without obscuring any details. In addition to the nice dynamism of light in the picture, I appreciate the drama that is contained in his face: his eyes, downcast and to the side, make it seem as if he’s slightly removed from the revelry around him, and the blur that envelops those around him further emphasizes his aloofness.

Before I continued the next roll of film, I wondered what the people within these photographs, especially this last one, were thinking. Had the music transported him to a different place? Were existential doubts plaguing him? Or was he considering what to have for dinner that night?

Thank you very much, and I hope you enjoyed these photographs too.

—David Meincke

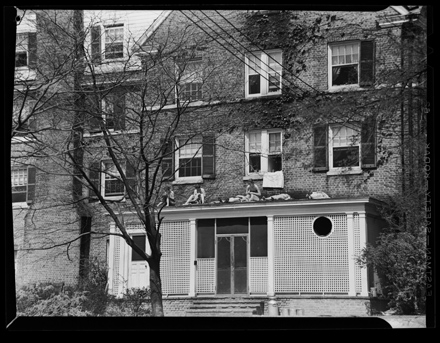

UPDATE 8/13/08 from Elizabeth: See the comments on this post for a discussion of whether the above photos might have been taken at “Singing on the Mountain.” Here’s a shot that shows performers in a tent-like enclosure, and that was taken at the Sing (according to Morton’s caption on the envelope). That caption is provided below.

Bascom Lamar Lunsford, known as “Minstrel of the Appalachians,” is one of America’s foremost authorities on the folk music of the Southern mountains, shown here singing with Miss Freida English. Lunceford [sic] is from South Turkey Creek, NC. All songs at “Singing on the Mountain” are religious, but Lunceford [sic] is famous for “Good Old Mountain Dew” and other songs which he wrote.

Oh boy! To make a long saga short, the AutoSlide accessory didn’t work from the very first day. After three visits from the Kodak repair man in consultation with Kodak repair HQ and an exchange of email to England, we decided to ship the unit to Rochester where they could compare its operation with working units on hand. Last Friday, after days and days and days of struggling, angst (I am not exaggerating), and detriment to my other responsibilities, the AutoSlide lived up to its billing. I loaded the carousel, hit the “go” button, and it worked flawlessly, generating nearly 600 scans during a day with a few interruptions and a couple meetings. A fully loaded carousel can be scanned in half an hour. For the techno crowd, those scans are 18MB TIFFs, 24-bit, with a pixel array of approximately 2000 x 3000 pixels. That 3000 pixels across the long dimension meets the “alternative minimum” in the National Archives and Records Administration

Oh boy! To make a long saga short, the AutoSlide accessory didn’t work from the very first day. After three visits from the Kodak repair man in consultation with Kodak repair HQ and an exchange of email to England, we decided to ship the unit to Rochester where they could compare its operation with working units on hand. Last Friday, after days and days and days of struggling, angst (I am not exaggerating), and detriment to my other responsibilities, the AutoSlide lived up to its billing. I loaded the carousel, hit the “go” button, and it worked flawlessly, generating nearly 600 scans during a day with a few interruptions and a couple meetings. A fully loaded carousel can be scanned in half an hour. For the techno crowd, those scans are 18MB TIFFs, 24-bit, with a pixel array of approximately 2000 x 3000 pixels. That 3000 pixels across the long dimension meets the “alternative minimum” in the National Archives and Records Administration