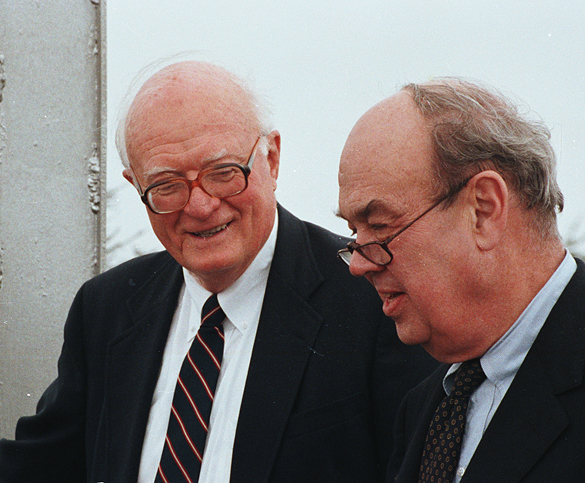

The Hugh Morton collection is part of the North Carolina Collection in large part because William Friday, UNC President Emeritus and friend of Morton, heartily and frequently encouraged Morton that his historically important photographic collection should be here. Robert Anthony, Curator of the North Carolina Collection, described Friday’s role as “key.” Friday, who passed away Friday morning—University Day—will be memorialized today at 10:00 a.m. in Memorial Hall. Morton collection volunteer and A View to Hugh contributor Jack Hilliard offers his memorial to William C. Friday in today’s post.

The University of North Carolina will bear the impress of this gifted and dedicated man for as long as it endures.— Archie K. Davis, President, North Caroliniana Society, May 4, 1984

Courage, manners and decency cost a person so little, but disregard them and see what you get.— William Friday, in a 1995 Associated Press interview.

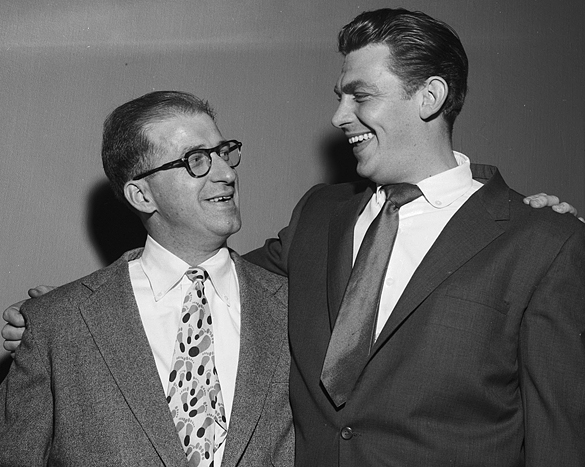

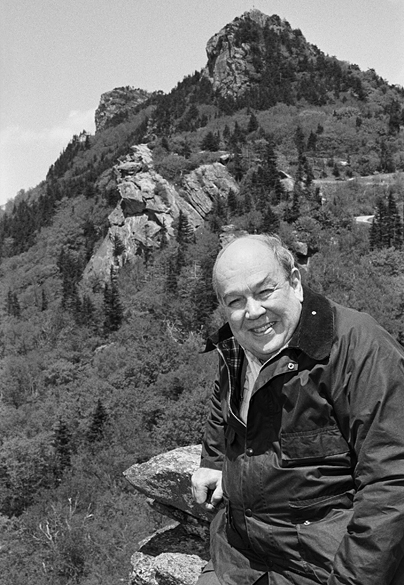

On the day the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill was to celebrate its 219th birthday, it mourned the loss of a legend. Dr. William C. (Bill) Friday, the individual who personified higher education in this state, died at age 92. Virginia Taylor, his special assistant, said the former UNC president died in his sleep early Friday morning, October 12, 2012.

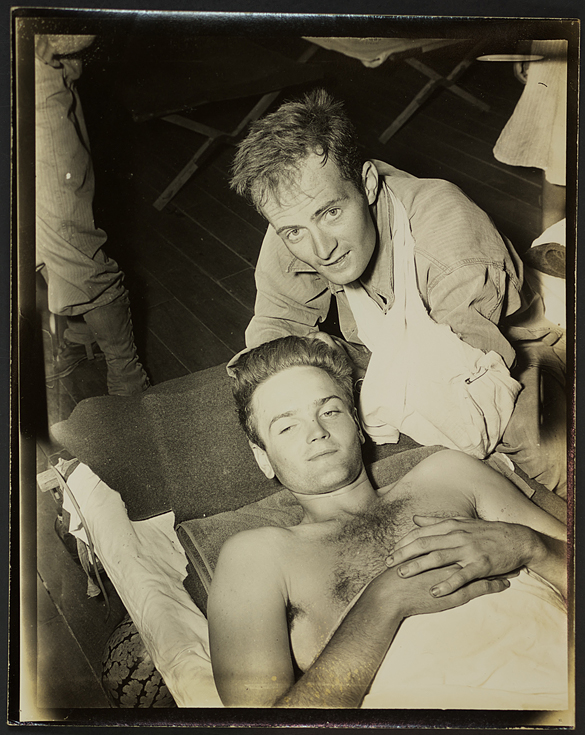

Bill Friday defined “The Greatest Generation,” during his service in World War II and the years that followed. For thirty of those years, he was president of the consolidated university system. During his tenure, he served with distinction under seven governors from Luther Hodges to James Martin. Under his leadership, higher education in the UNC system became a model for all to emulate.

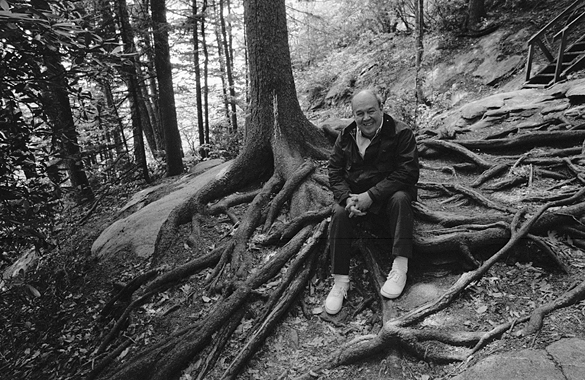

He was just 35 years old and the assistant to outgoing UNC President Gordon Gray when he was offered the position of Acting President of the Consolidated University of North Carolina. That was in 1956. He didn’t expect to stay long, telling a reporter at the time: “I expect that I will be in this place no more than a few months.” He remained until 1986. Although he retired in ‘86, he continued to be a vital part of his university.

At a reception and banquet in the Carolina Inn on June 7, 1996, Hugh Morton accepted the North Caroliniana Society award and in his remarks he said this about his old friend:

Bill Friday—I do not have to tell any of you—is probably the most respected person in our nation, not just North Carolina, in the field of higher education. To have him as a friend over the years has meant a whole lot to me.

I remember vividly the words of UNC Athletic Director Dick Baddour on November 5, 2004 at the Charlie Justice statue dedication. Baddour introduced Dr. Friday as “the most respected man in North Carolina.”

Last Wednesday, October 10th, in an interview with Rachel George of USA Today, Baddour said at the start of the NCAA investigation at UNC in the summer of 2010, “the telephone call to Bill Friday was the most difficult.” For more than thirty years, Friday, co-founder of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics, had fought for changes to prevent the exact type of violations ultimately found at UNC. On Friday morning Baddour described Bill Friday as “an absolute giant.”

In the Washington Post last week, Friday said while the investigations and violations at UNC are troubling, the school must move forward and improve. “It’s a very difficult thing to accept and I hope and pray that we’ve learned our lesson here, and I sure hope we have. But it’s a symptom of the commercialization of college sports all over the nation. I’m hoping that we can step forward and let’s move on and make the changes that are necessary, because change is necessary, and let’s go from here.”

“President Friday was the most significant educator in North Carolina in the 20th century,” said C. D. Spangler, Jr., who succeeded Friday as UNC president. Tom Ross, the current University President, said, “Bill Friday lived a life that exemplified everything that has made our University—and the state of North Carolina—great.”

UNC Chancellor Holden Thorpe added, “Bill Friday was committed to providing access to high-quality, affordable higher education to North Carolina students. He was tireless in his efforts to underscore the importance of higher education to people from all walks of life . . . .”

William Link, author of the 1995 book, William Friday: Power, Purpose and American Higher Education, said: “He was the person who kind of consolidated and built the system the way it is now. It’s gone through a lot of changes, but it’s Bill Friday’s university in a lot of ways.”

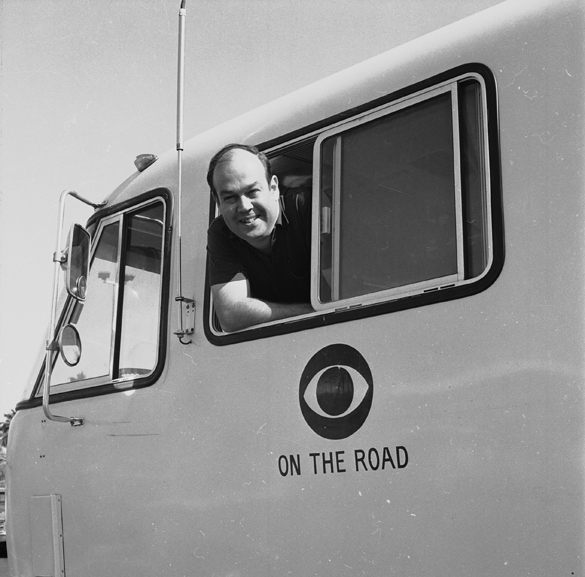

Many North Carolinians will remember Dr. Friday as a pioneer for public television and interviewer in his weekly TV program on WUNC-TV, “North Carolina People.” I remember on one of his early programs, he interviewed long-time sports broadcaster Ray Reeve. Reeve told about his first meeting with Friday and added, “I just assumed you would be governor someday.” I think there are many in this state who believe he would have been a great governor.

The state of North Carolina and the University lost a legend on October 12, 2012. Bill Friday will be missed, but on this day, I choose to believe he has joined a select group of individuals . . . a group that includes his dear friend Hugh Morton.

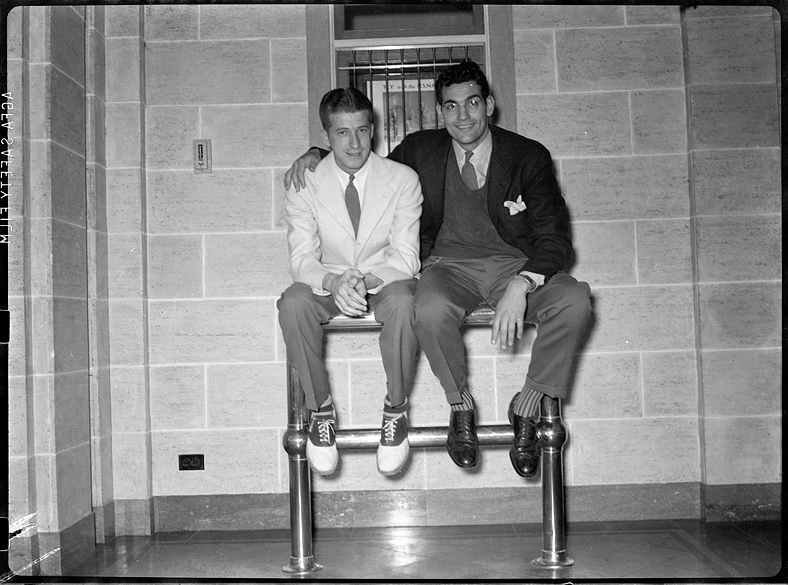

Currently there are thirty-eight photographs of Bill Friday in the online collection of Morton photographs.