Memorial Day seems a most appropriate occasion to highlight some of the images documenting Hugh Morton’s World War II experiences. The broad strokes of the story are well known: aware that he would end up in the military and hoping to receive an assignment in photography, Morton enlisted in October 1942 and was first posted at the U.S. Army Anti-Aircraft School at Camp Davis, taking pictures for training manuals.

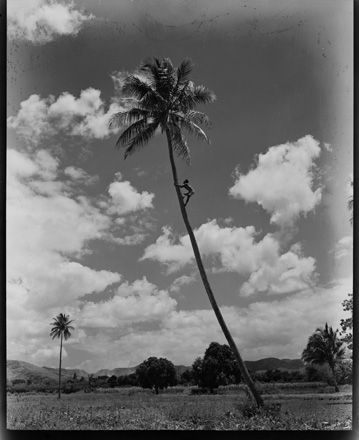

When he was sent to New Caledonia to report to the 161st Army Signal Corps Photo Company, he was surprised when his captain looked at him and said, “Morton, you look like a movie man.” (This was the first time he picked up a movie camera, but it certainly wouldn’t be the last—future blog posts will explore some of Morton’s later adventures in filmmaking). Since his wartime film footage went directly to the Army, we don’t have any of it in the collection here at UNC—but we do have a small number of still images taken by and of Morton during these eventful years.

Here’s Morton, in a photo by an unknown photographer, with his movie camera atop a B-24, the “Go Gettin’ Gal“:

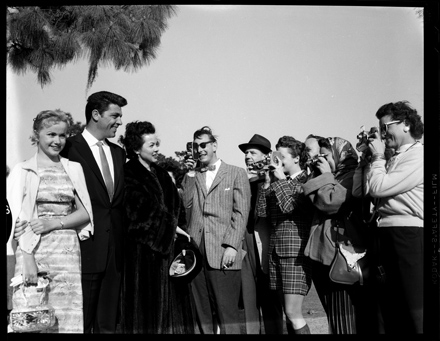

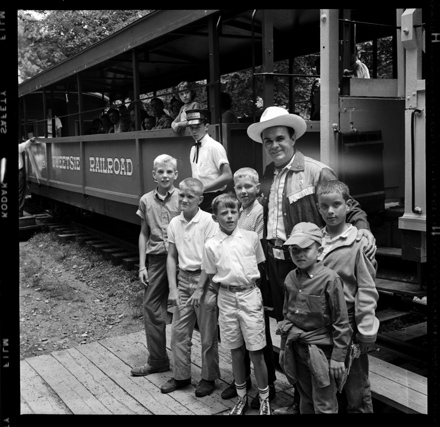

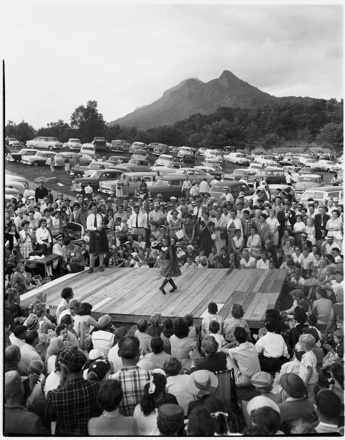

In 1944 Morton obtained an enjoyable assignment covering Bob Hope, Frances Langford, and Jerry Colonna as they entertained the troops at New Caledonia. In the booklet Sixty Years with a Camera, Morton described these as “three of the happiest days of my life…I rode in the same car with Bob and Jerry…during which they were cracking jokes and practicing their lines. It was a fun time.”

![Frances Langford and Bob Hope entertaining military personnel in New Caledonia, 1944 [cropped]](https://blogs.lib.unc.edu/morton/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2008/05/p081_ntbf4_000136_04.jpg)

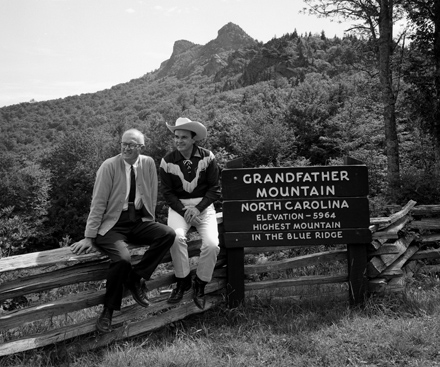

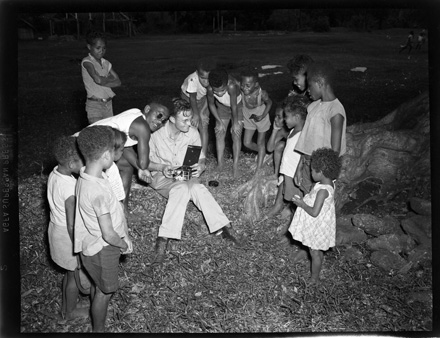

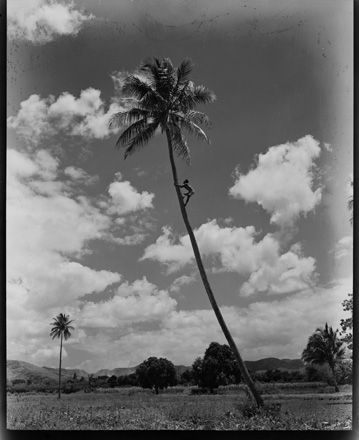

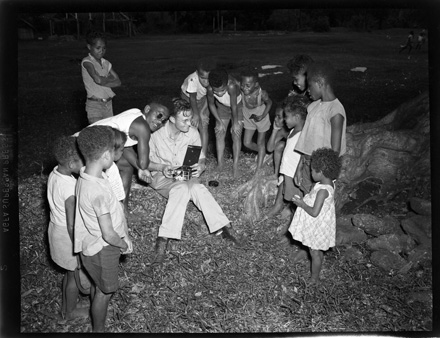

From there, he was sent briefly to Guadalcanal and Bougainville, which may be when the following images were snapped (the first is by Morton; the second shows Morton with his camera and a group of Pacific island children, taken by an unknown photographer):

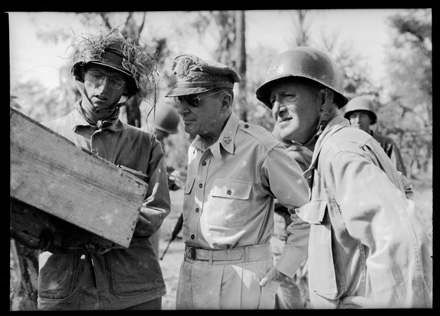

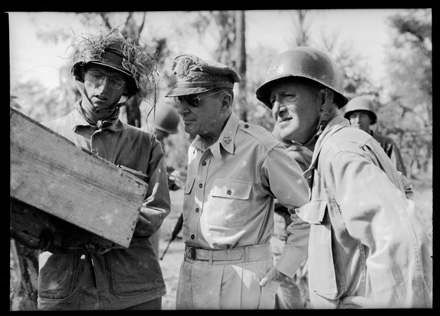

Morton then got his most intense assignment when he was sent to photograph the 25th Infantry Division as they invaded Luzon, in the Philippines, in early 1945. He obtained a few still shots of combat, and covered General Douglas MacArthur when he came to Luzon to inspect the 25th Division:

Shortly after MacArthur’s visit, Morton was wounded in an explosion—an incident for which he received a Purple Heart and Bronze Star, with citation, for exposing himself to danger in order to obtain high-quality, closeup images of the front lines. Morton recounts the incident in UNC-TV’s “Biographical Conversations” (video available online), claiming that the Speed Graphic camera he held in front of his face helped save him from further injury.

A note of interest: the Library of Congress holds the papers and photos of another member of the 161st Photographic Company, Charles Rosario Restifo. Be sure to check out Restifo’s detailed autobiography, wherein he discusses his training, camp life, and experiences in the Pacific, many of which would have been similar to or the same as Morton’s. I don’t believe Restifo is in the picture above, and he doesn’t mention Morton by name in the memoir, but it sounds like they were on many of the same assignments—in fact, if you look on page 98 of Restifo’s book, the image of MacArthur appears to be the exact same image as Morton’s (above)! Not just similar, but identical. Not sure how this happened.

One last Memorial Day musing: Morton didn’t leave his WW2 experiences behind him when he left the Pacific. As I discussed in a previous blog post, he deserves a lot of credit for the establishment of the USS North Carolina as a memorial to North Carolinians who died in WW2 service.

![Julia and Catherine [?] Morton in daffodil field at Castle Hayne[s], NC, circa early 1960s](https://blogs.lib.unc.edu/morton/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2008/05/castlehaynes.jpg)

![“Estonians,” Wilmington, NC waterfront [?], circa 1940s](https://blogs.lib.unc.edu/morton/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2008/05/p081_ntbf3_000141_10.jpg)

![Frances Langford and Bob Hope entertaining military personnel in New Caledonia, 1944 [cropped]](https://blogs.lib.unc.edu/morton/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2008/05/p081_ntbf4_000136_04.jpg)

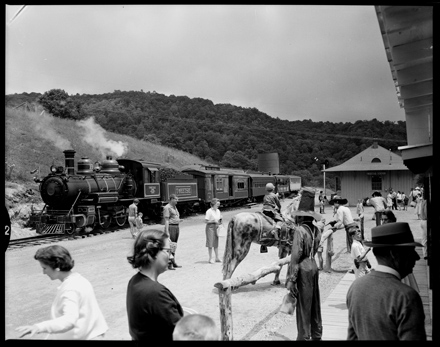

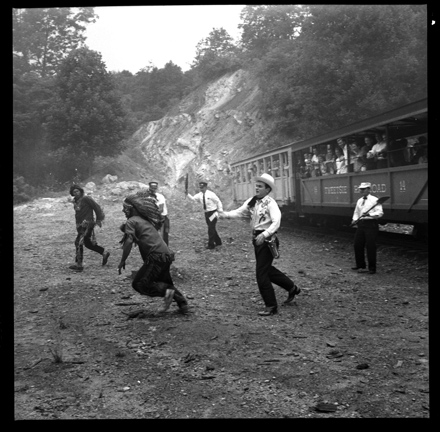

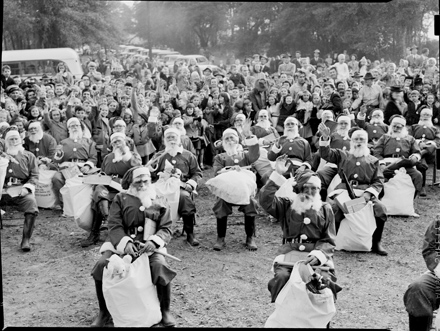

Wilmington’s 61st annual North Carolina

Wilmington’s 61st annual North Carolina