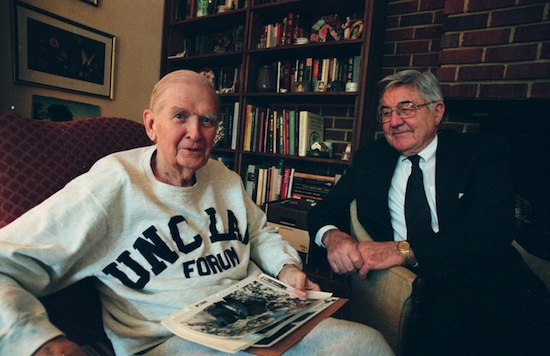

October 2nd, 2011 marked the 50th anniversary of the USS North Carolina’s arrival in Wilmington. Hugh Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard takes a look at the final days of the historic journey.

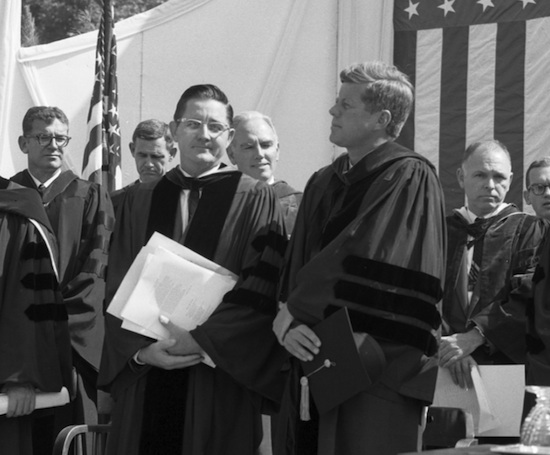

October 1961 was a busy month for photographer Hugh Morton. UNC’s football Tar Heels played host to Clemson, the North Carolina Trade Fair opened in Charlotte, President John F. Kennedy came to Chapel Hill for University Day, and the UNC basketball Tar Heels began practice under new head coach Dean Smith. But it would be the events of October 2nd that would become a defining episode in the legacy of Hugh Morton.

On October 17th, 1945 the battleship USS North Carolina (BB-55) entered Boston harbor. The ship had spent forty months in the Pacific during World War II traveling 307,000 miles. On its arrival, freighters, tugs, transports, and work boats cut loose with whistles, sirens, and bells for the North Carolina’s first salute back home. During World War II, the ship had been credited with twenty-four enemy planes, one enemy cargo ship, and had participated in every major offensive engagement in the Pacific from Guadalcanal to Tokyo Bay, earning fifteen battle stars. In the summer of 1946, it twice visited the Naval Academy at Annapolis to embark midshipmen for training cruises in the Caribbean. Then in October the North Carolina returned to its birthplace, the New York Navy Yard, for inactivation. On June 27th, 1947 it was decommissioned and assigned to the 16th Fleet (inactive), Battleship Division 4, Atlantic, relegated to fourteen years of retirement at Bayonne, New Jersey.

In 1958 a brief news item appeared in the media saying the World War II battleship was going to be scrapped by the United States Navy . . . sold for junk. When James S. Craig, Jr. of Wilmington heard the news, he was outraged. Craig set out to save the old ship. He was able to get Governor Luther Hodges’ attention and support as well as that of incoming Governor Terry Sanford. Hodges sent a dispatch to Washington requesting that the Department of the Navy postpone its plans to destroy, pending an investigation by the state into the possibility of salvaging the ship. On June 1st, 1960 the North Carolina was stricken from the official Navy list.

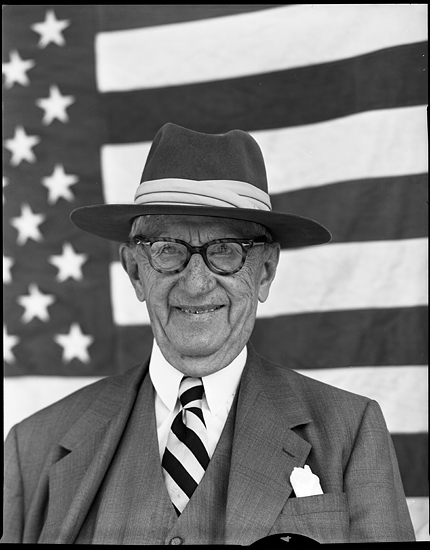

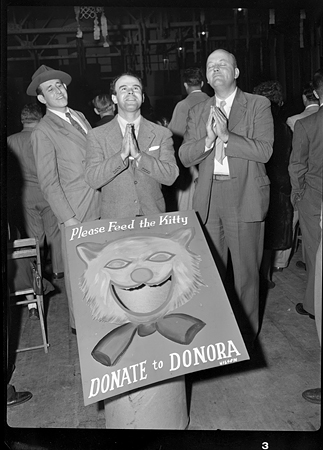

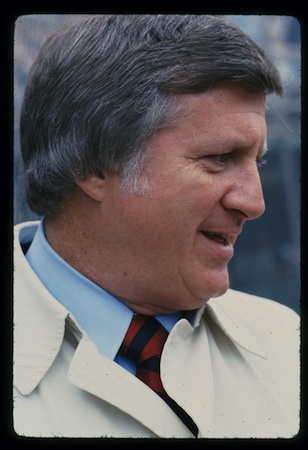

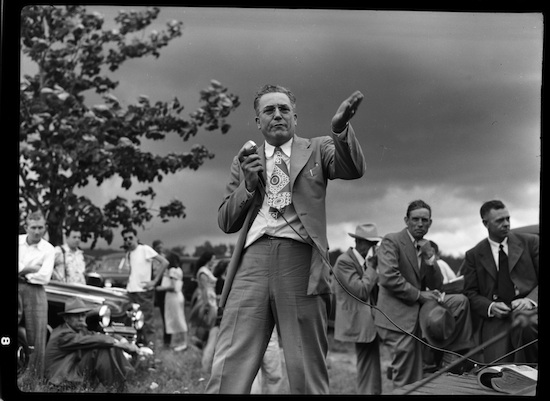

A little over five months later, on November 11th, 1960, Governor Hodges appointed the USS North Carolina Battleship Advisory Committee to investigate the feasibility of establishing the warship as a state memorial. In the spring of 1961, a bill was introduced in the legislature creating the USS North Carolina Battleship Commission. Hugh Morton was installed as chairman. During the next five months Morton and his commission initiated an intensive “Let’s bring the USS North Carolina home” campaign that raised the needed funds.

The United States Navy turned the battleship over to the state of North Carolina in a ceremony in Bayonne on September 6, 1961, with noted newsman Lowell Thomas as master of ceremonies. The ship’s towing to North Carolina was scheduled to begin on September 25th, but the remnants of Hurricane Esther had other ideas. A one-day delay was in order. The weather on Tuesday, September 26th was better and a proud warship headed home. Instead of an infamous journey to the junkyard, the USS North Carolina’s final voyage would be to a memorial berth in Wilmington, North Carolina—and the stage was set for a true North Carolina homecoming.

Soon after 9:00 a.m. on September 26th, the 45,000 ton USS North Carolina was moved away from its dock at Bayonne. Five tugs alongside and two others at the bow eased the battleship out into New York Harbor. Several ships in the harbor gave the majestic North Carolina salutes with their deep-throated horns as it moved down the channel through the narrows to lower New York Bay and then the open sea. Captain Axel Jorgensen of the lead tug Diana Moran answered each salute. For the next four days, the Diana Moran and its sister tug the Margaret Moran guided the big ship down the east coast. On Saturday afternoon, September 30th, the ship circled slowly the lee of Frying Pan Shoals, awaiting an early Sunday morning tide to assist its trip up the Cape Fear River. The plan was to enter Southport Harbor about 7:00 a.m. on Sunday, October 1st. But once again, mother nature stepped in: an unexpected northeaster blew in over coastal Carolina, bringing rain and low visibility.

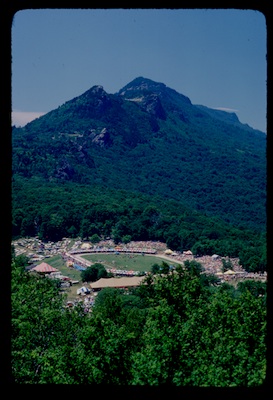

The battleship USS North Carolina spent its final night at sea just off Cape Hatteras—the “Graveyard of the Atlantic”—near the skeleton of the Laura E. Barnes, which wrecked off the Dare coast before the turn of the 20th century. Then at 8:00 a.m. on October 2nd, the ship began the last twenty-seven miles of its final journey. Thousands of spectators lined the river banks to watch. Scores of boats followed the big ship as it was pulled by the Coast Guard cutter Cherokee and guided up the winding channel by a fleet of eleven tug boats. As the North Carolina approached downtown Wilmington at 3:30 p.m., the crowds grew larger. Bleachers had been set up at the Customs House, and people could be seen hanging out of buildings trying to get a look at North Carolina’s newest tourist attraction. A band played “Anchors Aweigh” as the battlewagon cleared the Cape Fear River at 5:37 p.m.

“The berthing at Wilmington was one of the most tense moments in my lifetime,” said Morton in his 1996 book, Sixty Years With a Camera. “If it did not work, we knew we had a mighty big ship that would make a formidable dam on the Cape Fear River.” But it did work: at 5:40 p.m. on October 2nd, 1961, Rear Admiral William S. Maxwell, Jr. USN, Retired, superintendent of the Battleship Memorial, pronounced the USS North Carolina was home.

During World War II, the Japanese claimed six times to have sunk the North Carolina, but the gallant battleship survived every onslaught. And when it was doomed for the junkyard the people of the great state whose name it had carried during the war, and led by planner and organizer Hugh Morton, saved it for future generations.

Unfortunately, James S. (Jimmy) Craig, Jr. did not get to see the mighty battleship slip majestically into its memorial shrine at the Port of Wilmington. He was in the Army Burn Center at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, in critical condition from injuries suffered in an air show crash just eight days earlier. He died on October 14th, the day “The Showboat” first opened to the public.