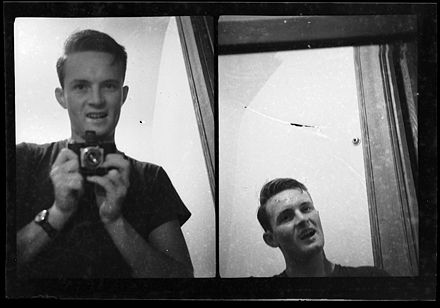

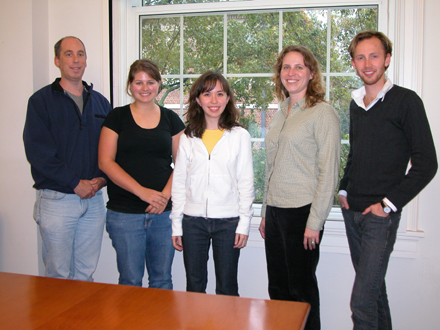

The image above (© 2008 Winston-Salem Journal photo/David Rolfe), which shows Stephen at the computer and me (Elizabeth “The Flash” Hull) operating the scanner, is from a recent article in the Winston-Salem Journal (2/17/2008 issue) about our work on the Morton collection (on the article page, scroll down to the “Multimedia” link to view more images, including some of Morton’s that you haven’t yet seen on A View to Hugh). (Note: as of 5/9/2008, the article no longer appears to be available online).

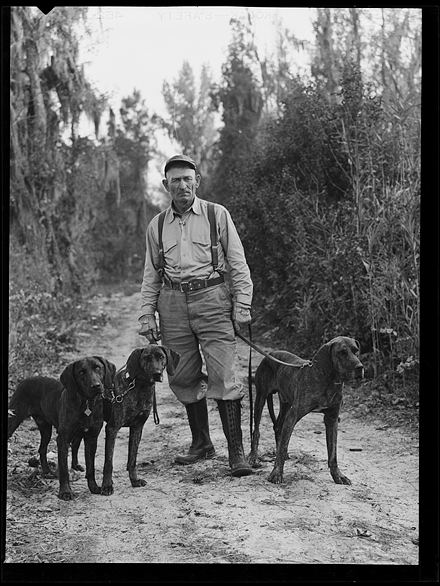

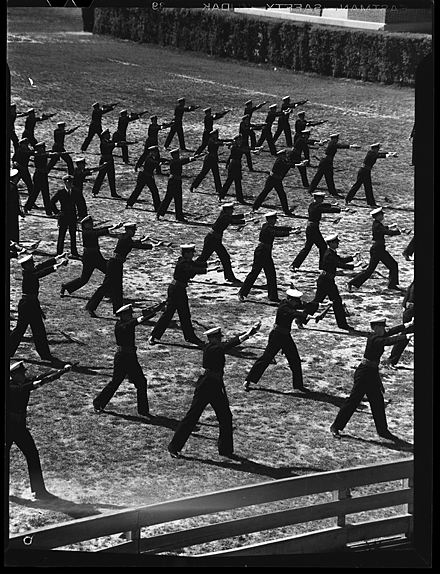

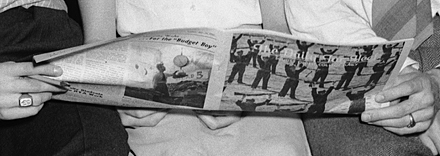

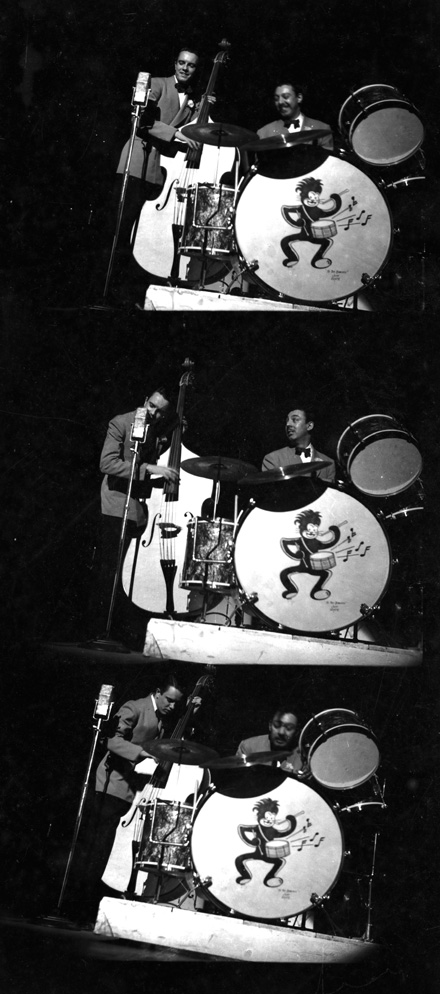

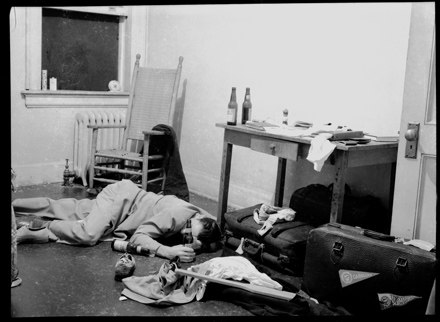

Yes, digitization of the Morton collection has begun . . . sort of. As you may have read in Stephen’s recent post, students from the digital libraries class are hard at work scanning black-and-white sheet film negatives—about 60 scans and counting so far—and the Library’s Digital Production Center should start on other parts of the collection soon.

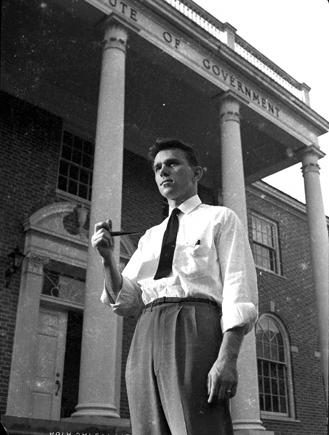

This way of doing things—scanning the collection in the middle of archival processing, rather than after it’s finished—is somewhat unorthodox and presents a number of challenges, especially in terms of how to maintain control over 1) the physical items in the collection (the actual negatives, prints, etc.), 2) the electronic versions we’re creating, and 3) the relationships between them.

We feel strongly about using this method, however, for a few reasons. The first, of most immediate importance to me, is that scanning will actually help me process the collection. I don’t know if you’ve ever sorted through a chaotic pile of 50,000 unlabeled negatives before (I’m guessing not), but for even the most seasoned negative-reader, it can be hard to tell what you’re looking at. Having positive versions in an electronic format will be incredibly useful for categorizing and identification.

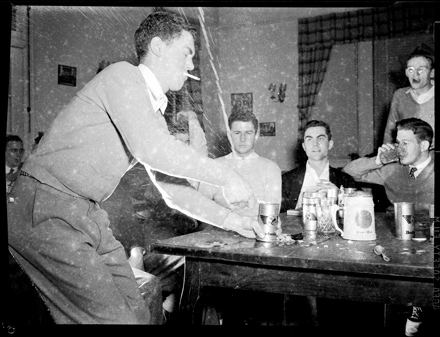

The second reason we want to do “mass digitization” of the Morton collection is so that we can make as much of it available as quickly as possible. This fits with a growing trend in the library/archives community, as shown by the report Shifting Gears: Gearing Up to Get Into the Flow published by Online Computer Library Center (OCLC). (This report was inspired by an all-day program entitled “Digitization Matters: Breaking Through the Barriers—Scaling Up Digitization of Special Collections,” attended by Stephen, at the Society of American Archivists annual meeting last August. Stephen’s series “200,000 slides” on this blog stems from ideas presented at that program).

The Shifting Gears report challenges libraries and archives to shift the focus of digitization away from “boutique” projects that either highlight marquee collections or “cherry-pick” from collections, scanning images at a very high resolution, describing them in great detail, and leaving the bulk of the archival holdings on the shelf where only in-person visitors can see them. Increasingly, the consensus is that we should be moving towards methods that emphasize access over preservation, aim for quantity over quality, and that let the user decide which “cherries” s/he wants to pick.

If this all sounds confusing, that’s because it is! We’re figuring it out as we go along. Ideas, advice, sympathy, encouragement, etc. are welcome as always.