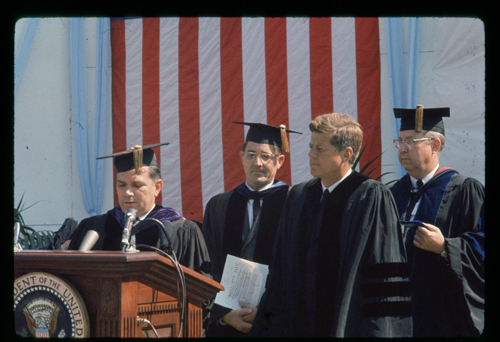

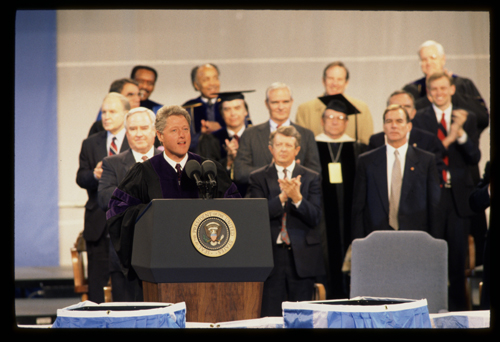

As UNC-Chapel Hill prepares for a visit by President Barack Obama on Tuesday, we thought it appropriate to recall previous Presidential visits to campus. The photographs below, by Hugh Morton, attest to visits by Presidents John F. Kennedy and Bill Clinton. Both visited on October 12, the anniversary date of when the cornerstone for the University was laid and a day known on campus as “University Day.” Kennedy visited in 1961 and Clinton, in 1993 to mark the University’s bicentennial.

James K. Polk was the first sitting President to visit campus. He arrived in Raleigh by train on a late spring day in 1847 and was met by a UNC professor and students. The President, born in Mecklenburg County and a member of UNC’s class of 1818, stayed overnight in the state capital and then left the next morning in a caravan of carriages and wagons. The trip from Raleigh to Chapel Hill took nine hours, with Polk stopping at farms along the way to water the horses, greet well-wishers and eat lunch.

Polk was officially welcomed by University President David Lowry Swain during a ceremony at Gerrard Hall. In response, he said, “Twenty-nine years have passed since I was here, yet I recognized as I came up a number of particular objects which were still the same in these halls in which I spent three years of my life and to the acquisitions here received I mainly attribute whatever success has attended the labor of my subsequent life.” The President stayed in Chapel Hill for two days, visiting with old friends and his former haunts, including his dorm room on the top of South Building. Polk ended his stay with attendance at Commencement. Upon his return to the White House he wrote in his diary that his visit has been “an exceedingly agreeable one.”

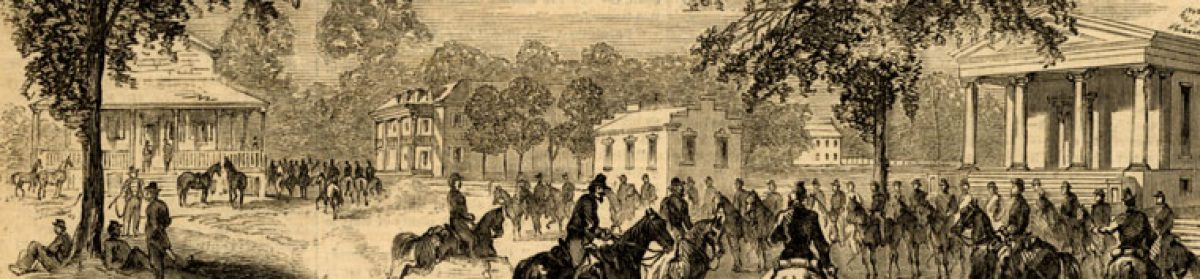

President James Buchanan was the next chief executive to visit Chapel Hill. He arrived on campus on June 1, 1859 during the University’s multi-day commencement exercises. Much like today, when gridlock is expected in parts of Chapel Hill, Buchanan’s visit placed a strain on the town. Anticipating a presidential visit, a large crowd–perhaps the largest to have ever attended graduation exercises to that date–arrived in Chapel Hill. Public accommodations and private homes were filled. As the NCC’s Harry McKown wrote in 2009:

Every carriage in the village and surrounding countryside had been pressed into service transporting the crowds, and when they were not sufficient, springless wagons took up the slack in a bone-jarring sort of way. The carriage of the President and official party was drawn by matched horses. Anything that could pull a wagon, including combinations of horses and mules, sufficed for the rest.

Buchanan’s visit occurred as sectional tensions over slavery were growing and talk of Southern secession was increasing. The President used his speech to the commencement audience to call for preservation of the Constitution.

“Let this Constitution be torn to atoms,” he said. “Let thirty republics rise up against each other; let the Union separate, and it would be the most fatal day for the liberties of the human race that ever dawned upon the land.”

The Union had separated, the Civil War had been fought and Reconstruction begun when the next Presidential visit to Chapel Hill took place. President Andrew Johnson, who was born in Raleigh, visited UNC for Commencement in 1867. Johnson was greeted by Swain, who was still serving as President of the University. From the steps of Swain’s home, the President, who had received very little formal education, told the audience, “North Carolina has not been, in the language of school men, exactly my alma mater, but still she is my mother and, God bless her, I am proud of her.” At the commencement ceremony in Gerrard Hall, the President and his fellow stage guests outnumbered the graduating class, which included only eleven men.

Although Woodrow Wilson visited the University before he was President and William Howard Taft, only two years after leaving the White House, seventy-one years would pass between Johnson’s trip and the arrival of the next sitting President. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was scheduled to speak at Kenan Stadium when he visited in early December 1938, but rain forced the President and his audience into Woollen Gymnasium. Roosevelt, who traveled by train from Warm Springs, Georgia, was greeted by thousands as he disembarked in Sanford. Large numbers of people were also gathered along the roadside to cheer the Presidential motorcade as it made its way to Chapel Hill. At the University, Woollen Gym was so packed that officials had to direct the overflow to Memorial Hall and three other buildings to which the President’s speech was piped. Roosevelt’s address to the Carolina Political Union, a student forum, was filmed by eight newsreel cameras and carried over 226 U.S. radio stations as well as broadcast overseas by shortwave. As Presidential historian William Leuchtenburg writes in “The Presidents Come to Chapel Hill”, Roosevelt’s speech prompted keen interest for several reasons.

At home, he had just suffered so severe a defeat in the midterm elections that many doubted that the liberal outlook would long survive. Abroad, Hitler had in September humiliated the democracies at Munich. Still worse, the Nazis had only days before carried out their horrifying pogrom against Jews. The President had not delivered an address since the midterm elections, and it was singular that he chose Chapel Hill as his venue….It was clearly young people, the people who carried hope for the future, he was seeking to reach.

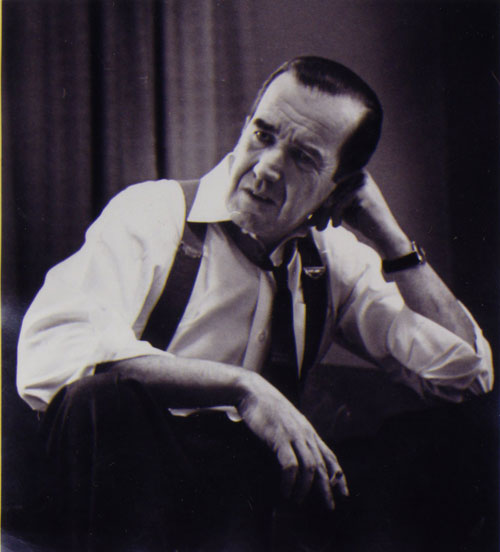

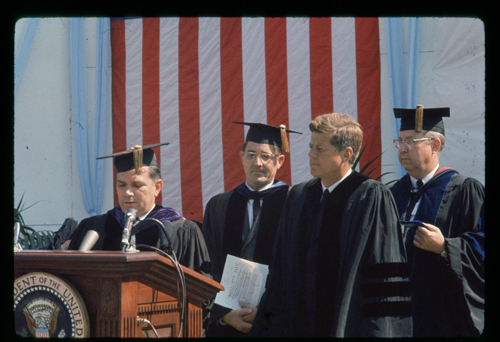

Kennedy arrived on campus eight months after taking office. About 40,000 people assembled in Kenan Stadium on a warm fall afternoon to listen to the President. Kennedy was awarded an honorary degree by Chancellor William Aycock before being introduced by William Friday, the president of the University system. In his speech, Kennedy praised North Carolina’s spirit of progressivism and the University’s “great traditions” and “devoted alumni.” He spoke of the concept of a university as defined by Woodrow Wilson. Then the President cited 19th century German statesman Otto von Bismarck, who once said that one-third of students at German universities break down from overwork, another third break down from “dissipation” and the other third ruled Germany. Then, with echoes of his famous “ask not” lines from his inauguration address, Kennedy looked at the UNC students and said, “I will leave it to each of you to decide in which category you will fall.”

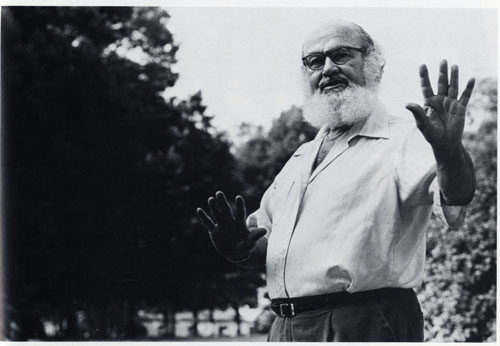

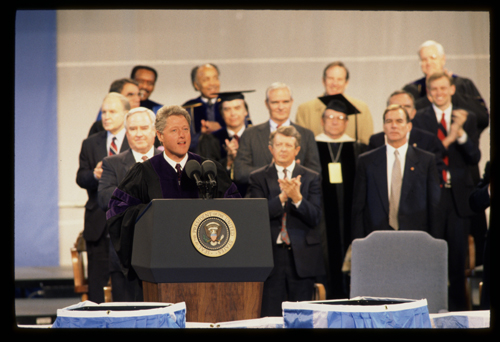

Thirty-two years to the day after Kennedy’s speech in Chapel Hill, Bill Clinton spoke to a capacity crowd during a chilly evening ceremony at Kenan Stadium. Like Kennedy, Clinton, too, had served barely more than eight months as President. And, he, too, praised the University for its openness to new ideas. “This University has produced enough excellence to fill a library or lead a nation,” he said. “As one who grew up in the South, I have long admired this University for understanding that our best traditions call on us to offer that light and liberty to all. Chapel Hill has always been filled with the progressive spirit.”

What are the chances that President Obama, too, will speak of the University’s progressive ideals and cite the University’s motto of lux libertas (light and liberty)? And how will his visit be recorded in the annals of the University? He’ll help write the first draft today.