![[Trees at top of hill covered with yellow wildflowers, circa 1980] [Trees at top of hill covered with yellow wildflowers, circa 1980]](https://blogs.lib.unc.edu/morton/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2008/09/p081_ptcs4_000499.jpg)

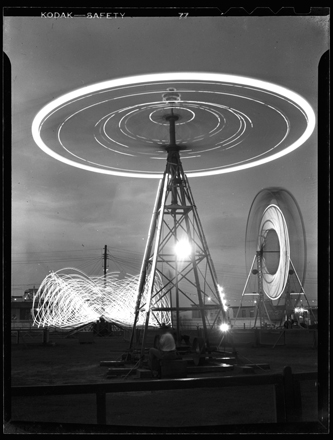

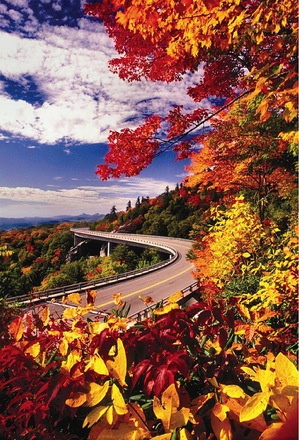

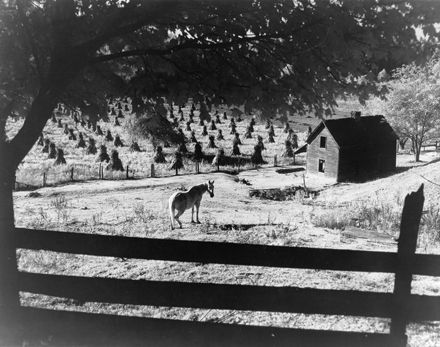

Well, I’m feeling pretty good about life (work life, anyway), which is why I’m sharing these happy “flowers and sunshine” images. I have just about wrapped up the second “pass” through the Morton negatives and transparencies — and it now looks like only a third and final pass will be required to get this stuff reasonably well organized, properly housed, and accessible. Mind you, there are still the slides and motion picture film to contend with! (I guess that’s why this is a multi-year processing project).

The transparencies, such as those in this post, were much simpler to plow through than the negatives—not only because they’re easier to look at (being positives), but because their numbers are much more manageable.

So, how exactly WILL the Morton collection be accessible, you ask? One of the ways is through an online archival “finding aid.” What is a finding aid, you may then wonder? Extremely valid question. Here’s how the Society of American Archivists defines it:

Finding Aid: n. ~ 1. A tool that facilitates discovery of information within a collection of records. – 2. A description of records that gives the repository physical and intellectual control over the materials and that assists users to gain access to and understand the materials.

Finding aids (and archival collections) are typically organized into groups of like material called “series.” The following links will lead you to two examples for collections in the UNC-Chapel Hill Libraries: Preliminary Inventory of the Don Sturkey Photographic Negatives (for a photographic collection) and Inventory of the Terry Sanford Papers (for a manuscript collection).

The Morton finding aid, however, will look pretty different from both of these. For one thing, it will be much, much, MUCH longer (remember, half a million items!). For another, there’s a strong likelihood that the Morton finding aid will be presented in series by subject, rather than by date or format.

So, this means that instead of having series names like “Pre-1960 Material,” as in the Terry Sanford example, or “Negatives,” as in the Don Sturkey example, the Morton finding aid will be arranged into groupings called, for instance, “Sports,” “Grandfather Mountain,” “Nature/Scenic,” and “North Carolina.” Within those series would be listed groupings (or “sub-series”) of images that reflect that subject, regardless of their format.

Further explanation, as well as a discussion of the difficulties of arranging and describing a photographic collection in this manner (and believe me, there are plenty!), will have to wait for a future blog post.

![[Trees at top of hill covered with yellow wildflowers, circa 1980] [Trees at top of hill covered with yellow wildflowers, circa 1980]](https://blogs.lib.unc.edu/morton/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2008/09/p081_ptcs4_000499.jpg)

![[Azalea] Vaseyi [on Grandfather Mountain], 1955](https://blogs.lib.unc.edu/morton/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2008/05/p081_ntbs4_000134_01.jpg)

![Rare Bats [on Grandfather Mountain], Spring 1984](https://blogs.lib.unc.edu/morton/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2008/05/bats.jpg)