“In North Carolina, the toll: 19 people killed; 15,000 homes or other buildings completely destroyed or with major damages; 39,000 homes or other buildings with minor damage. Total property losses: $125 million.”

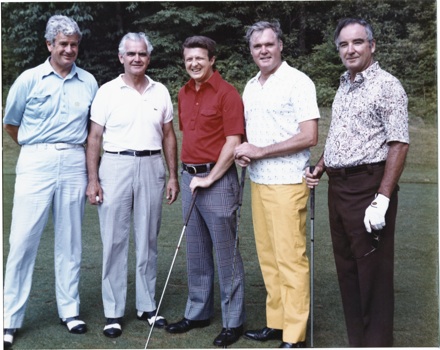

This quotation comes from page 15 of the book Making a Difference in North Carolina, co-written by Hugh Morton and Edward L. Rankin. Though most of the pages are filled with intimate portraits of politicians and other influential individuals who operated on the state as well as national level, one chapter is devoted to Hurricane Hazel (arguably just as influential a figure as the others in the book).

Hazel visited the Coastal Carolinas as a Category 4 hurricane in the middle of October of 1954 after striking Haiti with deadly results. As we in the Carolinas are just coming out of the zone of influence of another H-named storm and, as a nation, are about to be assaulted by an actual hurricane, it seems appropriate to post some pictures that Hugh Morton took during the 1954 hurricane season. All of these pictures are from Carolina Beach, NC.

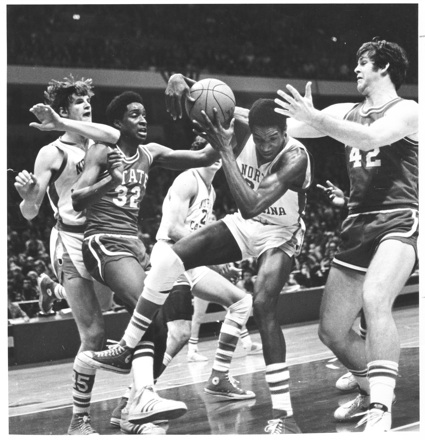

Let’s begin with an award-winning photo:

Some more pictures that were really interesting and are in need of identification are ones that appear to be the wrecked remnants of a boardwalk.

I was able to identify one of the stores, the Ocean Plaza Bathhouse (that appears in the background of the picture, but gets more prominence in other ones in the series), a somewhat well-known institution of the time at Carolina Beach. Does this place still exist? Or did a hurricane and/or a decline in interest towards bath houses contribute to its closing? And how about the rest of the Carolina Beach boardwalk?

This whale, probably a familiar symbol to those who visited and lived in Carolina Beach, seems to be faring better than some of the other structures. The woman standing to the left seems to be weathering the storm in her own right, but I wonder what she was doing out in the storm? Perhaps she was a local politician, a member of the chamber of commerce, or a friend of Hugh Morton. I suppose everyone has their reasons for facing a storm; I suppose it still happens today.

If you are one of those individuals, until the hurricane season is over, be safe!

–David

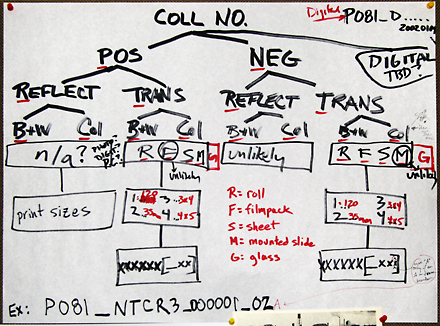

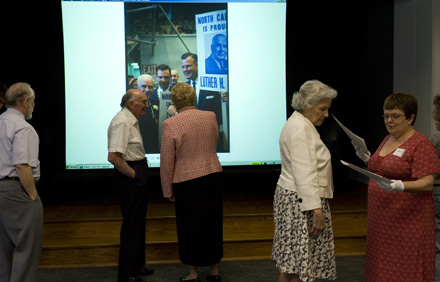

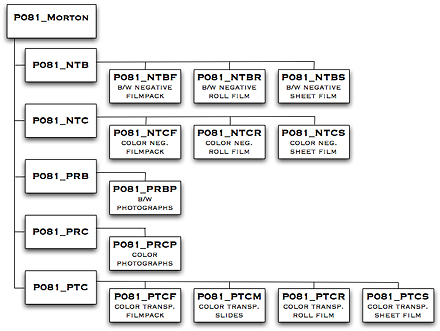

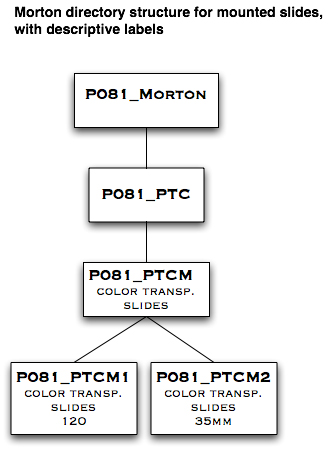

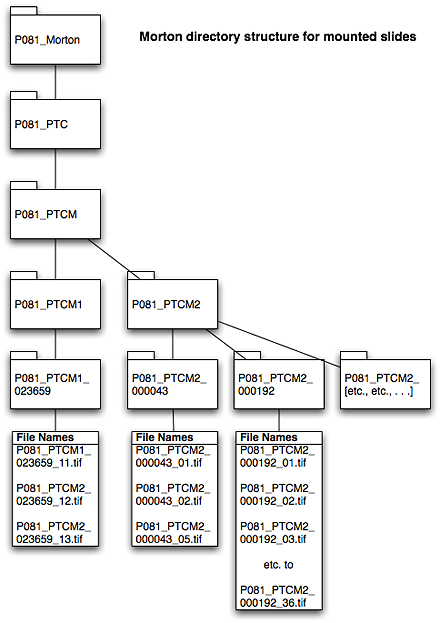

I gave a quick “tour” of the Morton collection recently to a group of local archivists who specialize in audio-visual materials, and after explaining a bit to them about the file naming scheme we’ve adopted, they suggested I share it on the blog. WARNING: some may find this a bit dry, but hopefully it will be useful (or at least mildly interesting) to others.

I gave a quick “tour” of the Morton collection recently to a group of local archivists who specialize in audio-visual materials, and after explaining a bit to them about the file naming scheme we’ve adopted, they suggested I share it on the blog. WARNING: some may find this a bit dry, but hopefully it will be useful (or at least mildly interesting) to others.