In case you haven’t heard (perhaps you’ve been hibernating), 2010 marks the 75th anniversary of the Blue Ridge Parkway. Numerous events throughout the year will help mark this occasion, including a symposium next week at Appalachian State University, at which UNC Libraries’ Natasha Smith, Elise Moore, and faculty advisor Anne Mitchell Whisnant will unveil the exciting Driving Through Time digital project! (More on that after it’s launched).

In case you haven’t heard (perhaps you’ve been hibernating), 2010 marks the 75th anniversary of the Blue Ridge Parkway. Numerous events throughout the year will help mark this occasion, including a symposium next week at Appalachian State University, at which UNC Libraries’ Natasha Smith, Elise Moore, and faculty advisor Anne Mitchell Whisnant will unveil the exciting Driving Through Time digital project! (More on that after it’s launched).

Luckily, we were able to steal Dr. Whisnant (author of the 2006 book Super-Scenic Motorway: A Blue Ridge Parkway History) away long enough to write an essay for our Worth 1,000 Words project. It’s now available, and is entitled Roads Taken and Not Taken: Images and the Story of the Blue Ridge Parkway ‘Missing Link.’

It’s no secret that determining the route for the last leg of the Parkway was a protracted, complicated, and divisive process, but one that ultimately resulted in the much-celebrated (and photographed) Linn Cove Viaduct (shown from the air at left). In her essay, Whisnant uses some of Morton’s own images to shed new light on this conflict. She also provides a crucial backdrop for some of Morton’s later environmental work, which will be examined in future Worth 1,000 Words essays.

We look forward to receiving your thoughts and comments!

Category: Landmarks & Attractions

A Springtime 'Variety Vacationland'

Here in Chapel Hill, the daffodils are blooming, the world is mud-luscious, and the sweet sound of sneezing floats on the breeze. It must be spring!

As the buds begin to blossom, so too does the tourist season in North Carolina. To provide some perspective on the development of the tourism industry in the Old North State (and Hugh Morton’s role in it), we offer our newest essay in the Worth 1,000 Words series: Selling North Carolina, One Image at a Time, by Richard Starnes.

Starnes is an historian specializing in southern history and Appalachia, Associate Professor and History Department Chair at Western Carolina University, and author of the 2005 book Creating the Land of the Sky: Tourism and Society in Western North Carolina.

Read, share, discuss, and enjoy.

Grandfather Mountain's new "Top Shop"

Recently Elizabeth told me about the demolition of the old “Top Shop” and the ongoing construction of a new shop on the summit of Grandfather Mountain. I grew up in North Carolina, and my childhood was full of visits to Grandfather Mountain; I loved searching through the gift shop after I walked over the Mile High Swinging Bridge. So to honor the transition from old to new, this post will be dedicated to the progression of development on the summit of Grandfather. (This is just a brief summary; perhaps the staff at Grandfather can provide a more detailed chronology?)

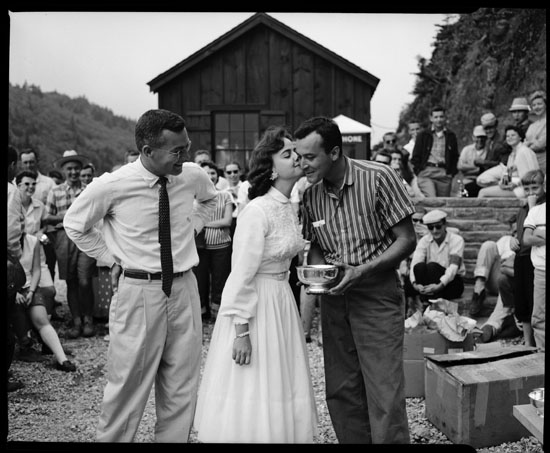

Originally, the gift shop/visitors center on the summit of Grandfather was just a little wooden building, with a stone bathhouse next door, as shown above. The first picture is a view of the first visitor’s center. I like this picture because it shows the quaint nature of the original design of the Grandfather summit. The second picture shows golfer Billy Joe Patton (left) and others at a trophy ceremony for the “Sports Car Hill Climb” event that used to be held annually. The wooden visitors center is in the background. I chose this picture because it shows how the summit was used as an outdoor gathering space.

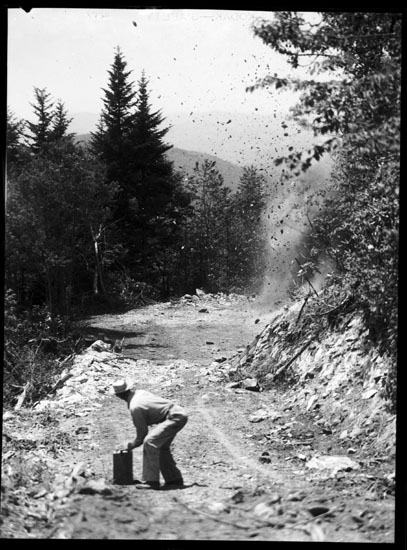

Morton inherited the land at Grandfather Mountain in 1952. In the 1950s (according to the book Grandfather Mountain by Miles Tager), “the postwar economic boom had by this time returned visitors to the region, opened up by the Parkway and other roads,” after the scarcity of visitors during the Great Depression. Morton took advantage of the prosperity of the 1950s by constructing a new road to the summit, a new parking lot, and a new gift shop. The picture above shows construction of the road to the summit.

The new building, dubbed the “Top Shop,” was constructed in 1961. The first picture is of construction of “Top Shop” visitors center, right before it was completed in 1961. The next picture is of the “Top Shop” soon after it was built. And the last picture is of tourists browsing the new gift shop.

Grandfather Mountain has gone through many phases to become the popular attraction that it is today. The new shop will have many advantages over the old one, will be less of an obstruction to the view of Grandfather’s profile, and is much needed because of the weather damage that happens to buildings on the summit. (To see pictures of the construction of the newest “Top Shop,” click here). But though these transitions at Grandfather Mountain are all for the best, it is nice to look back at the simple beginnings of the wooden gift shop sitting on a barely developed piece of land.

An ongoing "miracle in the hills"

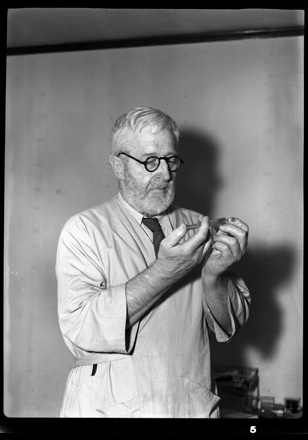

A few weeks ago I received a friendly call from Mr. Bob Martin, an Avery County resident, author, admirer of Hugh Morton, and former director of the Crossnore School, a private, non-profit home and school in the NC mountains serving (primarily) abused and neglected children. Bob’s call triggered a memory of a set of Morton images that had caught my interest a while back—two circa 1940s portraits of Dr. Eustace H. Sloop, co-founder (with his wife Mary Martin Sloop) of the Crossnore School.

While perhaps not the most aesthetically pleasing example of Morton’s work, I like these Sloop portraits because they show him engaged in his primary calling, medicine. Both Eustace and his wife Mary were trained as doctors, and arrived in Crossnore in 1913 planning to provide much-needed medical assistance in the Appalachian Mountains. Mary soon devoted herself to improving public education as well, founding the live-in school in 1917; it was re-incorporated in 1939 as “a child-caring institution, whose purpose shall be to provide a home and industrial and vocational training for orphan, half-orphan, and deserted children . . . preference being given to mountain children” (from p. 8 of Philis Alvic’s 1998 history, The Weaving Room of Crossnore School).

You can learn about Mary T. Martin Sloop’s remarkable life through her 1953 memoir Miracle in the Hills: The lively personal story of a woman doctor’s forty-year crusade in the mountains of North Carolina, written with LeGette Blythe. As Blythe described Sloop, “no mold shaped her, no die stamped her out. . . . She is one of our last examples of the sturdy, energetic pioneer women who played such an important role in the settling of America.”

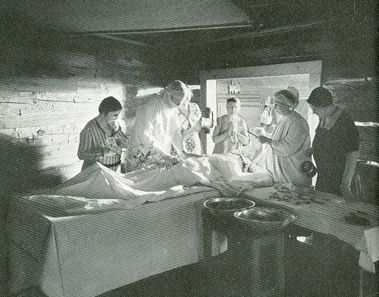

I wish I had more illustrative material for this post, e.g. a portrait of Mary Sloop — but Morton doesn’t seem to have taken any. Bayard Wootten, however, did; she took this shot of the Sloops performing surgery in the field, circa 1917. (It was included in a 2005 exhibit put on by the North Carolina Collection Gallery entitled “Sour Stomachs, Galloping Headaches,” along with a few other early images from the Crossnore School, including Wootten’s photograph of outdoor surgery.)

"The sweet music of those bells…"

Note from Elizabeth: Thanksgiving Day marks the 78th anniversary of the dedication of UNC-Chapel Hill’s Morehead-Patterson Bell Tower. Morton Collection volunteer Jack Hilliard explores the Bell Tower’s history below.

Late summer 1947 . . .”It was a dark and stormy night.” Hugh Morton had set up his camera down the street from the Morehead-Patterson Bell Tower to photograph the University landmark during a thunderstorm. Little did he know at the time that one of the photographs from that session would wind up on the cover of two prominent North Carolina magazines simultaneously. That shot of the Tower (above), shrouded in haze with lightning flashing above, would be featured on the front cover of The Alumni Review issue of October, 1947, as well as The State magazine for October 25, 1947.

Over the years the Tower became a favorite photographic subject for Morton. His Bell Tower shots graced the cover of The State at least two more times, February 25, 1950 and January, 1974.

In the early 1920s John Motley Morehead III proposed the idea of a Bell Tower to UNC President Harry Woodburn Chase. As part of the post-World War I building boom on campus, South Building was remodeled and Morehead suggested putting a bell tower on top of the building. The University “powers that be” wanted to maintain the historical integrity of the old structure, so they declined the offer. Then, in 1926, the administration drew up preliminary plans for what would become Wilson Library. Again, Morehead offered to pay for a bell tower on top of the library, but University Librarian Louis Round Wilson had already decided that “his” building would be domed.

Later, when University trustees moved the flagpole from McCorkle Place to Polk Place, Morehead again suggested a bell tower, and again the administration declined his offer. At this point Morehead enlisted the help of Rufus Lenoir Patterson II, prominent New York businessman, and the two families, along with University officials, came to an agreement that the Bell Tower would be placed between Wilson Library and Kenan Stadium.

On Thanksgiving Day, November 26, 1931, Governor O. Max Gardner delivered the acceptance address, concluding with these words:

I dedicate this tower and the sweet music of these bells to the future upbuilding of this institution and this state, knowing full well that on this campus the sons of North Carolina will be inspired by the harmony of these chimes and will here catch the vision and follow the gleam.

Later that afternoon, as was the Thanksgiving tradition in those days, Carolina played Virginia in Kenan Stadium.

Originally the bells were rung manually, but now the 14-bell carillon operates electronically, and has been heard as far away as Durham. The largest bell, which tolls the hour, is engraved with the name of Governor John Motley Morehead, grandfather of the bell’s creator.

The 172-foot Morehead-Patterson Bell Tower actually rises about 200 feet, since it is built on a knoll, and it is surrounded by a hedge and lawn designed by William C. Coker, botany professor and creator of the campus Arboretum.

The photograph on page 94 of Morton’s 2006 book, Hugh Morton: North Carolina Photographer, shows the Morehead-Patterson Bell Tower at sunset—the way it often looks as it serenades the dispersing crowd after a great Tar Heel victory in Kenan, like the 13 to 6 win on Thanksgiving Day 1931.

—Jack Hilliard

Who is Singleton Anderson?

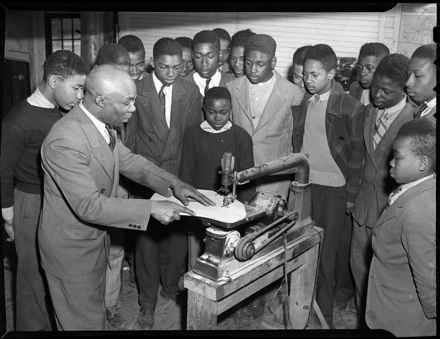

This is a question I was asking myself from the time I started working on the Morton collection until recently, when I happily discovered the answer. A particular batch of Morton negatives labeled “Singleton C. Anderson, Rocky Pt.” caught my attention when I was making my first survey of Morton’s photographs. I noticed them because 1) they were striking black-and-white images from the circa 1950 period, and 2) they depicted African Americans in a non-athletic setting (somewhat unusual in Morton’s work).

Some quick Google searches at the time were fruitless; I suspected the images showed scenes from a Rosenwald School, but I didn’t have time to look into it any further. But the images, and Anderson, stuck with me. I just had a feeling they were important. So when I came upon them again recently during processing, I figured “what the heck,” and tried another Google search. Jackpot!

The site I found, Under the Kudzu, is run by educator and writer Claudia Stack, who is now in the process of creating a feature-length documentary film focused on the Rosenwald school movement as shown through two schools in Pender County, NC: the Canetuck Rosenwald School, a primary school, and the Pender County Training School, a high school. PCTS was located in, yes, Rocky Point. I emailed Claudia immediately and attached jpegs of the images included in this blog post. The next day, I got this reply:

I am ASTOUNDED at these images . . . I have been researching PCTS and Singleton C. Anderson’s profound impact on the region for the past six years, but images are very hard to come by. That is partly, I think, because he was a humble man, and partly because a tragic house fire claimed the life of his wife, Vanetta Anderson, and also all of their papers and pictures.

So, who in fact WAS Singleton C. Anderson?

Stories of a Not-So-Buried Life

Though this admission may cause some to question my Tar Heel credentials, I will confess that I am currently reading Thomas Wolfe‘s Look Homeward, Angel for the very first time. It’s a moving and incredibly rich book, though, okay, occasionally long-winded. As I read, I am struck again and again by the vibrant imagery of Wolfe’s language — his descriptions of nature and food, in particular, truly engage the senses.

Thus it would come as no surprise that someone as visually-minded as Hugh Morton would feel some affinity to Wolfe — not to mention that both were “big men on campus” at UNC-Chapel Hill in times of war (Wolfe during WWI and Morton during WWII). In 1941 (only a few years after Wolfe’s untimely death) Morton had his own first-person encounter with Angel‘s milieu. As he recounts on page 7 of Sixty Years with a Camera:

While I was a student at Chapel Hill, the CAROLINA MAGAZINE sent me to Asheville to interview Julia Wolfe, the mother of novelist Thomas Wolfe, at the Old Kentucky Home. You remember that Tom wasn’t very kind to his mother in his book….and for a while I wasn’t sure that I was going to be kind to her. But after I’d been there for a day, she warmed up, became very friendly, and took me out to the cemetery to see his grave.

Ed Rankin describes this same event on page 249 of Making a Difference in NC, quoting Morton as saying that “[Mrs. Wolfe] was obviously proud of her son, proud of the success his works enjoyed…but she had mixed feelings about what he had written about her. Perhaps she didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.”

I have to say that these Morton images certainly conform to my mental picture of Angel‘s Eliza Gant, the white-faced, pursed-lipped penny-pincher who endlessly tormented her youngest son Eugene.

The North Carolina Collection here in Wilson Library holds several Wolfe-related collections, including a photograph collection. Library staff are currently working on an overhaul of the online access to these collections, so keep your eye out for some nice new finding aids!

And speaking of Wolfe-related imagery, UNC’s Center for the Study of the American South is currently exhibiting artist Douglas Gorsline’s rarely-shown original drawings for the first illustrated edition of Angel, loaned from the North Carolina Collection. The drawings are on display through September 30, with a public reception next Thursday (8/27) featuring live music and dramatic readings from the novel.

"Windmill City"

“Today’s quiz: what had 2000 kilowatts, created devotees called ‘wooshies’, was the largest of its kind in the world, and didn’t work?

Answer: the U.S. Department of Energy wind-powered electric generator constructed on Howard’s Knob in October, 1978.”

–from the Mountain Times

Add this to the canon of “World’s Largest” in North Carolina (at least for a time): Boone’s famous experiment in wind power, dedicated thirty years ago this week (on July 12, 1979). As a Boone native (albeit a young one at that point), I certainly remember the windmill, but wasn’t aware of the full background of the project, or of the “cult” that formed around it — a Mountain Times feature, “The 20th Century: High Country History,” provides the relevant details, and Blue Ridge blog presents additional photos and remembrances.

The windmill surely created a buzz in Boone for a brief time — perhaps a bit too much buzz, as reported by Time magazine. Concerns over the windmill’s noise and ineffectiveness (plus the Reagan administration’s eventual pulling of funding for alternative energy research) ultimately doomed the project, and the windmill was taken down in 1983. I’m a little unclear on what, if any, role the Mountain Ridge Protection Act of 1983 (aka the “Ridge Law,” an effort in which Hugh Morton was heavily involved) played in all of this, other than that it exempted windmills from its ban on tall structures along the ridgeline. Can anyone fill in some of those details?

Meanwhile, NC windmills are back in the news today, as the General Assembly debates a possible windmill ban in the mountains — a ban it appears the majority of the public opposes. The NC Wind Energy website provides a wealth of information on the issue. I wonder what Morton’s position would have been?

Battle for the Beacon

Note from Elizabeth: This is the fourth post researched and written by volunteer Jack Hilliard. Ten years ago today, on July 9, 1999, the move of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse to its new location was completed.

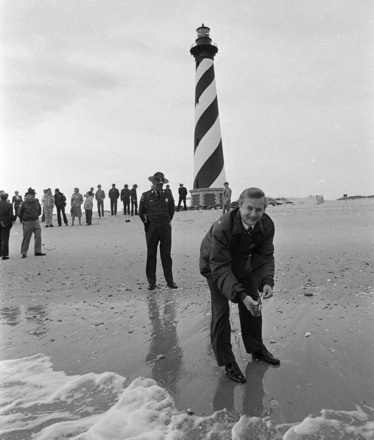

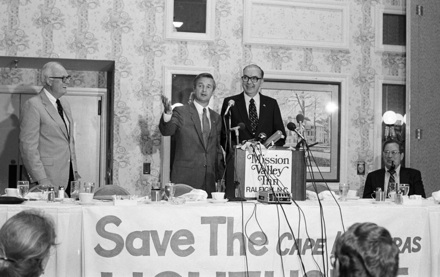

It wasn’t difficult to recognize Hugh Morton when he came to Greensboro in the spring of 1982 for the annual Governor’s Conference on Travel and Tourism. He was the gentleman in the Carolina blue jacket and the yellow tie embroidered with an image of the Hatteras Lighthouse. His lapel button identified him as “Keeper of the Light.”

A year before, Morton had formed the “Save the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Committee,” in response to the growing concerns about the safety of the 129-year-old structure. His committee read like a who’s who in North Carolina: Morton was even able to get his friends (and political foes) Democratic Governor Jim Hunt and Republican Senator Jesse Helms to lead the project. (The two would engage in a 1984 Senate contest that Newsweek magazine called “the most colorful, expensive, and nasty Senate contest in the country,” but in 1981 they were on the same team).

A year before, Morton had formed the “Save the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Committee,” in response to the growing concerns about the safety of the 129-year-old structure. His committee read like a who’s who in North Carolina: Morton was even able to get his friends (and political foes) Democratic Governor Jim Hunt and Republican Senator Jesse Helms to lead the project. (The two would engage in a 1984 Senate contest that Newsweek magazine called “the most colorful, expensive, and nasty Senate contest in the country,” but in 1981 they were on the same team).

This powerful group was able to raise $500,000 in a very short time, with Morton using some of the same techniques that he had used 20 years before to bring the Battleship USS North Carolina to Wilmington. The money was used for sandbags, sand fences, and Seascape synthetic seaweed. All of these measures were extremely helpful in building up the beach around the lighthouse.

This powerful group was able to raise $500,000 in a very short time, with Morton using some of the same techniques that he had used 20 years before to bring the Battleship USS North Carolina to Wilmington. The money was used for sandbags, sand fences, and Seascape synthetic seaweed. All of these measures were extremely helpful in building up the beach around the lighthouse.

Morton and Hunt were able to literally measure their success. In an interview for the December, 1997 issue of Lighthouse Digest magazine, Morton said:

“Governor Hunt and I took a tape measure; one of us stood at the base of the light and the other took the tape to the water’s edge–and it was not low tide either. The tape showed it was 310 feet from the water to the tower–quite an improvement over the less than 100-feet when the project started. The seaweed had trapped the sand moving south and built up the land under the water as well as the beach itself.”

"Driving through Time" project funded

Exciting news! A new two-year digital publishing initiative called Driving through Time: The Digital Blue Ridge Parkway in North Carolina has been approved for funding by the Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA). Work on the new collection begins July 1, and will be heavily based on findings and experimentation from other GIS (Geographic Information Systems)-based projects developed by UNC Libraries and their partners: Going to the Show and North Carolina Maps. (By the way, if you haven’t yet explored these collections, you simply must).

We’re especially thrilled because Driving through Time will include some of Hugh Morton’s Parkway photographs. Here’s a summary of the project provided by the Carolina Digital Library & Archives:

Driving through Time: The Digital Blue Ridge Parkway in North Carolina will present an innovative, visually- and spatially-based model for documenting the twentieth-century history of a seventeen-county section of the North Carolina mountains. The project will feature historic maps, photographs, postcards, government documents, and newspaper clippings, each of which will be assigned geographic coordinates so that it can be viewed on a map, enabling users to visualize and analyze the impact of the Blue Ridge Parkway on the people and landscape in western North Carolina.

Primary sources will be drawn from the collections of the UNC-Chapel Hill University Library, the Blue Ridge Parkway Headquarters, and the North Carolina State Archives. These materials are especially significant in that they document one of North Carolina’s most popular tourist attractions, but also in the way that they help to illuminate the way that the Blue Ridge Parkway transformed the communities through which it passed. In addition to the digitized primary sources, the project will include scholarly analyses of aspects of the development of the Blue Ridge Parkway in North Carolina, and an educational component designed for K-12 teachers and students.

Using digital technologies to open a new window on the history of the Parkway and its region is especially timely considering the approach of the Parkway’s 75th anniversary in 2010 and the National Park Service’s 100th anniversary in 2016. This project is certain to be a valuable and popular resource for millions of tourists as well as for teachers, students, and historians, both within North Carolina and beyond.