Sometimes you have to make exceptions. A little more than a year ago, I was contacted by the designers assigned to decorate the interior of the then-under construction (and now newly opened) NC Cancer Hospital. They were seeking Hugh Morton photographs of the North Carolina landscape to be made into very large panels for public areas of the hospital. This was a great opportunity to place some of Hugh Morton’s photographs in highly visible locations within a prominent and important facility, and to assist our sister institution. The problem was, a little more than year ago, we were a little less than knowledgeable about what photographs were where in the collection. (That is one of the reasons the collection was closed to researchers until very recently). What to do?

We made an exception. I explained the status of the collection and its limited access at that point, but also asked the designer to go through Morton’s published books for images that we could try to find or approximate. Once they compiled that list, I turned it over to Elizabeth, who combed through photographs she could access to find suitable images. The design firm made their selections, Elizabeth turned over the material to the Carolina Digital Library and Archives scanning technician, and then we waited a year to see the results.

Earlier this month, Elizabeth and I had the opportunity to tour the building and see the installations. To say it is a beautiful building is not saying enough, and Morton’s photographs are wonderful splashes of color and place that contribute to the overall atmosphere inside.

The photographs you see here illustrate a few of those installations. In the photograph above, Elizabeth stands next to a very long panoramic composite mural that repeats slices of several Morton images. Below is the lobby and information desk inside the main entrance (featuring a Morton mountain panorama).

Here’s a couple of installations behind reception desks. Sorry . . . the hospital is designed to let in lots of the outside light and views, so it was impossible to photograph during the day without getting reflections!

Shown above with her back to the camera is our tour guide Ellen de Graffenreid, Director of Communications & Marketing for the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. (Thank you, Ellen!)

If this next image isn’t too tiny on your computer screen, you can play “Where’s Elizabeth?”!

It was particularly satisfying to tour this impressive facility and see how Hugh Morton’s photographs add to the overall aesthetic of the building, especially since he was a victim of cancer himself.

Stephen Fletcher

The "Man Who Pastorized Swing"

A few weeks ago, Elizabeth pointed out a few unidentified jazz photographs and asked me if I could write up a post on them to see who they might be. One photograph, seen here, ended up being easily identified: it is big band leader Tony Pastor (1907-1969), “The Man Who Pastorized Swing.”

The background was the giveaway. On the upper left are the bottom of the numbers “941,” and on the right are an “R” and the rounded edge of another letter. A quick check through the UNC yearbook Yackety Yack revealed the bands who played at UNC dances for that year. That tidbit and some name “Googling” matched the face in the Morton photograph with the face of Pastor in other portraits on the Web for the easy ID.

Pastor’s band was the headline act for the Spring 1941 Junior and Senior dances on Friday and Saturday, 16-17 May 1941. Pastor’s troupe performed four dance sets, and the 5:00-5:25 dance was broadcast “coast-to-coast” over the NBC radio network via WPTF in Raleigh. As far as we can tell, this is the only surviving negative of Pastor’s performances at Chapel Hill. Pastor also performed three gigs at the Carolina Theater in Durham that Thursday at 3:00, 7:00, and 9:30. The tickets for the matinee shows were 28 cents, while the evening show cost 44 cents.

The drummer in the background of Morton’s photograph is either Johnny Morris or Morrison (I’ve see both in print but I think it’s Morris). One of Pastor’s signature tunes was “Paradiddle Joe,” which featured the drummer. YouTube has a version with Henry “Riggs” Guidotti on the kit. Not pictured is Eugenie Baird, who joined Pastor’s band just two weeks before coming to Durham and Chapel Hill.

How did the students rate Pastor? Well, the Daily Tar Heel wrote a review on 1 June 1941 of the bands who came to campus for dances. They decided that Pastor, “even to those addicted to Paradiddle Joe and Let’s Do It, was disappointing. By Saturday night his blasting, commercial arrangements were grating on everybody near enough to the bandstand to hear him.”

The Greens of Summer?

Maybe only photographers would think of this question, but if Paul Simon’s verdant lyric about Kodachrome giving us “the greens of summer” was true, then why, oh why, was Fujichrome invented? At the risk oversimplification, let’s take a look at that question. After all, in his own way, Hugh Morton did!

Maybe only photographers would think of this question, but if Paul Simon’s verdant lyric about Kodachrome giving us “the greens of summer” was true, then why, oh why, was Fujichrome invented? At the risk oversimplification, let’s take a look at that question. After all, in his own way, Hugh Morton did!

The demise of Kodak’s Kodachrome film has made the media rounds recently, and soon after the announcement I thought of writing a post about it (because Morton first used Kodachrome in the early 1950s).

Then, we rediscovered a set of 35mm slides that Morton made where he photographed several subjects with three different films, including Kodachrome. Two of those scenes are represented here as side-by-side scans. Morton’s approach was likely loading three cameras with three different films, setting up a tripod, then swapping out the cameras to make three separate exposures. He picked several scenes until he completed the three rolls of film, then processed all three rolls and compared the results, scene by scene.

To keep this from turning into a complicated photography lesson, let’s just note that manufacturers make different films with different “extended sensitivities.” That means that one film may be more sensitive to reds and yellows, for example, and another film may be more sensitive to greens and blues. This is the case between Kodachrome and Fujichrome, and Kodachrome and Ektachrome. Can you see the differences between the films in the two examples?

When the news of Kodachrome’s death first came out, I had my natural kicked-in-the-gut reaction I get when another hallmark of film photography comes to its fateful end. A friend and I were ruefully exchanging emails discussing Kodachrome’s death blow, and I asked, “When is the last time you shot Kodachrome?” For both of us, the answer was quite a long time ago—so long ago that neither of us could remember precisely. In fact, digital photography has meant that I haven’t shot any type of film in about five years.

One of the standout benefits of digital photography over film photography is its ability to compensate for different types of lighting or adjust the rendering of colors in a particular scene from exposure to exposure, rather than from roll to roll. Depending on your camera and/or imaging software, you can make one exposure, then walk to your computer and easily create variations from that one image that would look similar to all three of Morton’s film examples—and more. This is one more reason that digital photograhy is supplanting film photography, and a contributing factor to the end of Kodachrome’s fabled history.

The Honorary Tar Heels

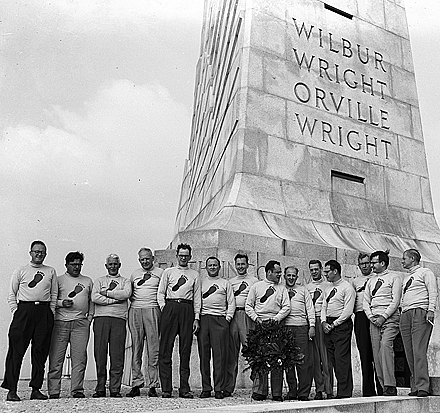

In the post, “Don’t Smoke Your Eye Out” I related the course of events that led to identifying Joe Clark, HBSS, who up to that point was an unidentified person in a Hugh Morton photograph, standing next to Andy Griffith as he aimed a slingshot while simultaneously holding a cigarette. The above photograph, a group portrait of the 1956 Honorary Tar Heels dinner attendees in New York City, was a key to identifying Clark (second from the right standing next to Hugh Morton). I didn’t know at the time I wrote the post that the original negative was in the collection, so I present it to you in this post. Bob Garland (on the far left holding a camera) likely made the photograph, as his name is on the negative.

This post will introduce you to the Honorary Tar Heels (HTH), a lose-knit social club formed in 1946. But first, a special treat: in a comment for “Don’t Smoke Your Eye Out,” Julia Morton mentioned a photograph of Joe Clark standing on the top of the Mile High Swinging Bridge at Grandfather Mountain. We found the negative; daring stuff!!!

This post will introduce you to the Honorary Tar Heels (HTH), a lose-knit social club formed in 1946. But first, a special treat: in a comment for “Don’t Smoke Your Eye Out,” Julia Morton mentioned a photograph of Joe Clark standing on the top of the Mile High Swinging Bridge at Grandfather Mountain. We found the negative; daring stuff!!!

The Honorary Tar Heels began in 1946. During that year, Curtis Publishing (of Saturday Evening Post and Ladies Home Journal fame) sent writer Francis X. Martinez and photographer William S. Springfield to North Carolina to work on a “red-herring” (pre-publication) edition of a magazine to be called Holiday. Bill Sharpe, head of the Division of Advertising and News of the North Carolina Department of Conservation and Development, guided the pair from one end of North Carolina to the other. During their three-week sojourn, Springfield took to imitating the locals—eating their food, drinking their liquor, and imitating their dialects. After they left, Sharpe asked Governor R. Gregg Cherry to sign a “corny little proclamation” making Springfield an “Honorary Tar Heel,” to which Cherry obliged. Springfield proudly showed his certificate around and before too long other visiting photographers and writers began requesting the appellation.

The Honorary Tar Heels began in 1946. During that year, Curtis Publishing (of Saturday Evening Post and Ladies Home Journal fame) sent writer Francis X. Martinez and photographer William S. Springfield to North Carolina to work on a “red-herring” (pre-publication) edition of a magazine to be called Holiday. Bill Sharpe, head of the Division of Advertising and News of the North Carolina Department of Conservation and Development, guided the pair from one end of North Carolina to the other. During their three-week sojourn, Springfield took to imitating the locals—eating their food, drinking their liquor, and imitating their dialects. After they left, Sharpe asked Governor R. Gregg Cherry to sign a “corny little proclamation” making Springfield an “Honorary Tar Heel,” to which Cherry obliged. Springfield proudly showed his certificate around and before too long other visiting photographers and writers began requesting the appellation.

Sharpe knew Joe Massoletti, a New York City restauranteur with a cottage at Hatteras, and the two shared several mutual friends among the newly anointed HTHs. Massoletti suggested to Sharpe that they be invited to Hatteras sometime in 1947 for a weekend of fishing. To make it a festive event, Massoletti supplied a chef and a waiter from New York, and had food flown from New York to Manteo and then boated on the Pamlico Sound to Hatteras. A group of thirteen HTHs, including Massoletti as host, attended the gathering that included writers and photographers from the New York Times, Life Magazine, and National Geographic. A group portrait of those who attended, probably made by Holiday staff photographer Al DeLardi, can be found on the cover of The Honorary Tar Heels, 1946-1967: A Pictorial History. Governor Cherry also attended, although he arrived after the photographs were shot.

Members of the budding affiliation continued to meet two or three times a year—most likely through the efforts of Sharpe as a means to maintain his media connections—at places such as Nags Head, Cataloochee Ranch, Lake Logan, Morehead City, Wrightsville, Linville, New York, Washington, and Philadelphia.

But what of Hugh Morton and Holiday, the publication that served as the unlikely catalyst for the HTH?

But what of Hugh Morton and Holiday, the publication that served as the unlikely catalyst for the HTH?

Martinez and Stringfield teamed up to produce “Village of Stars,” an article about the Lost Colony drama on Roanoke Island, for the fourth issue of Holiday published in June 1946. Though not a wide-ranging essay on the state, their three-week trek may have laid the ground work for the magazine’s October 1947 issue that featured North Carolina in a lengthy article written by News and Observer editor Jonathan Daniels. The article featured photographs by DeLardi, one of which depicted four men playing cards while two men examine a fishing rod and reel next to a fireplace inside Massoletti’s cottage and may well be members of the HTHs. The heavily illustrated twenty-six page article also included images by several photographers, including eleven by Hugh Morton.

Don't smoke your eye out!

Pappy says: “Never shoot at the bull’s eye, shoot at the center of the bull’s eye.”

—from I Remember, by Joe Clark

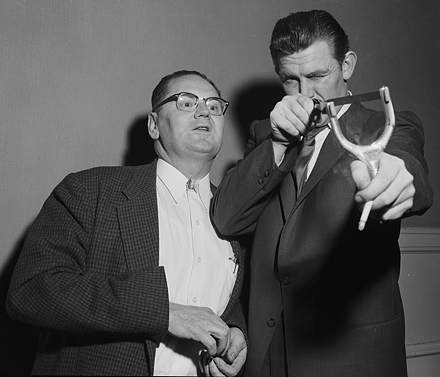

The photograph above (cropped) of Andy Griffith aiming a slingshot while holding a cigarette in the same hand was among the first negatives from the Morton collection that I scanned soon after the collection arrived, and it has remained one of my favorites. It just seems so funny to me to have both in your hand at the same time. I’ve used that photograph in public presentations several times and have asked most audiences if anyone knew who the fellow on the left might be. No one ever came up with his name.

Elizabeth has been egging me to write more posts, and she thought the recently enacted North Carolina law banning indoor smoking would be a good stepping off point for an entry on some of Hugh Morton’s scenic landscapes of tobacco fields. The Andy Griffith image, however, quickly popped into my head so I asked her and David if there might be some other interesting indoor smoking images in the collection. Neither could recall any, but Elizabeth pointed me to Morton’s book Making a Difference in North Carolina to see if there might be some in there.

Other than an unlit cigar, I did not find any smoking photographs. But on page 283 . . . Eureka! . . . I saw a group photograph with then Governor Luther H. Hodges, Sr. and Andy Griffith—not of them smoking, but including someone standing next to Griffith’s left side who is completely cropped out of the photograph except for his coat sleeve and the tiniest corner of his eyeglasses. That sliver immediately triggered my brain cells that are associated with the Griffith slingshot image. Looking back through the scanned negatives, David pulled up the image used for the book. Here’s an uncropped version of the group photograph:

Notice the slingshot in the hand of our mystery gentleman.

The caption for the photograph in Making a Difference describes the gathered posers as members of the Honorary Tar Heels in New York City, so off I went to the Library’s catalog. It revealed a record for a booklet in the amazingly deep North Carolina Collection—The Honorary Tar Heels 1946-1967: A Pictorial History written by Bill Sharpe. Inside the booklet is a group portrait of the attendees of their 21 January 1956 dinner in New York City, and standing next to Hugh Morton, with his armed wrapped around him, is the mystery man—identified as “Joe Clark, H.B.S.S., Detroit, Michigan.”

H.B.S.S?

“Googling” that acronym led to a web page at thefreedictionary.com that presents five possible definitions. “Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution” didn’t apply, nor did the next few, but wait . . . the last one? Well that would be “Hill Billy Snap Shooter (Joe Clark photography book)” . . . and this mystery enters into the realm of the surreal!!! That revelation explains another photograph in the collection, shown below, with our now identified Joe Clark aiming to shoot with a camera rather than a slingshot. That’s Hugh Morton on the right, . . . and that’s Bill Sharpe in the middle, smoking indoors in New York City.

Once again I cannot stump the North Carolina Collection, which has Clark’s 1969 book, I Remember, a collection of his poems and photographs. And there it is, on the spine and the title page, “Joe Clark HBSS.” Luther Hodges, Sr. signed the inside front endpaper of the book in 1970, and on the next page is written “Joe Clark—the author is an old friend and an Honorary Tar Heel.” Davis Library pitched in, too, with Clark’s earlier book, Back Home, published in 1965. The front endpaper of that book depicts Clark with a camera over his shoulder—and a slingshot in his hands. More research revealed Clark’s other books: Detroit, God’s Greatest City published in 1962, Lynchburg (1971), Tennessee Hill Folk (1973), and Up the Hollow from Lynchburg (1975). The Bentley Library at the University of Michigan has a modest collection of Clarke’s published works and a videotape interview of him featuring his son, Junebug Clark.

Another Morton collection mystery solved! Oh, one last thing . . . . Since the group portrait in Making a Difference in North Carolina is cropped to the right of Griffith, the above uncropped version unveils a gentleman on the far right. That’s photographer Joe Costa.

As for the rest of the Honorary Tar Heels story? Well, there are more photographs in the Morton collection of this and other of the group’s events. Looks like Elizabeth won’t have to egg me on for another post!

Hi-De-Ho

We’ve written only two posts so far about Hugh Morton’s jazz photographs, so it seemed like a good time for another post. Here goes . . . and if you promise not to bust your conk, I’ll promise not to beat up my chops!

Among the unidentified jazz negatives are three that I suspected from the music stands (and later confirmed) are from a Cab Calloway performance. We can’t say where the frolic pad for the show was, so please beef us if you are hep to that. If you were there, then I’m sure it must have been a real killer-diller with plenty of mitt pounding, so please slide your jib about it with the rest of us. If not and you dig research, get in there!

In the photograph above, Calloway looks dicty, in a fine vine, with two buddy-ghees wearing some hard drapes. Actually, all three gates are togged to the bricks!!! One photograph only shows an unknown canary, a fine dinner donning flowery dry-goods that may be Calloway’s older sister Blanche . . . but that’s just a guess.

And the third photograph depicts Calloway and the chirp above hittin’ some Armstrongs.

Just having these negatives is a real mezz, but their condition is sadder than a map. The 127 format roll film negatives are on an acetate base, and antihalation layer deterioration has caused them to have a splotchy blue discoloration. (And that’s not jive talk!) Scanning the negatives in grayscale eliminates the blue discoloration, but the images still retain a splotchy look. Despite that bring down, they are likely from the late 1930s and I suspect fairly rare.

If you got all that, then you are a hep cat that’s got your boots on! If you are unhep, you may want to consult the bible, The New Cab Calloway’s Hepster Dictionary: Language of Jive [an online list; the 1944 edition of his dictionary is an appendix in Calloway’s autobiography, Of Minnie the Moocher & Me (1976).]

Pheeewww! I think I’ll head home now and guzzle some foam!

Hugh MacRae and Castle Hayne

On December 7, 1908 Hugh MacRae—Hugh Morton’s grandfather—addressed a gathering at the Astor Hotel in New York City. Located on Broadway at West 44th Street, the then-four-year-old hotel was a Beaux-Arts architectural gem built by William Waldorf Astor for $7 million ($160 to 180 million today) situated on Longacre (later Times) Square. MacRae’s audience was the North Carolina Society of New York, and the guest of honor was United States president-elect William Howard Taft.

The evening’s theme was “some of the large forces of southern progress” and the speaker’s table included W.W. Finley, president of the Southern Railway, who spoke on “The Railroad and the People”; James Y. Joyner, North Carolina Superintendent of Public Instruction, who conveyed “What the Public School is Doing”; and Dr. James H. Dillard, president of the Janes Board, who talked about “The Negro and His Training.” MacRae’s topic was “Bringing Immigrants to the South.”

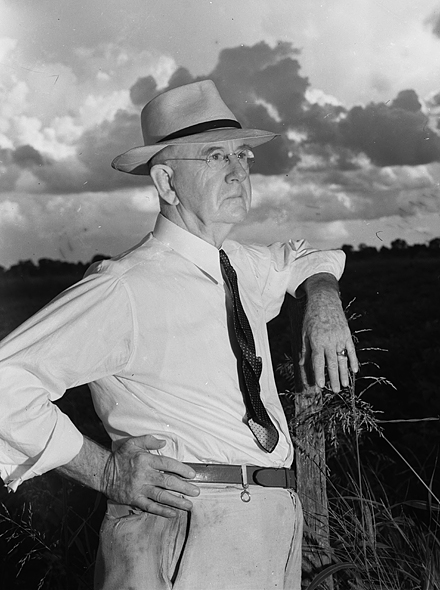

One hundred years later, MacRae’s topic is where my head has been planted for the past few months as I have been preparing an exhibit for the North Carolina Collection Gallery entitled, “Cultivating ‘The Great Winter Garden’: Immigrant Colonies in Eastern North Carolina, 1868-1940.” This exhibit will be opening in early March, and two Hugh Morton images—both likely from the 1940s—will probably be displayed: an outdoor portrait of MacRae (cropped by me) likely dating from the 1940s, and a westward-looking bird’s-eye-view of Castle Hayne and vicinity, a community north of Wilmington originally named Spring Garden that was established by 1861 but later changed to Castle Hayne.

Shortly after the turn of the 19th century, MacRae mounted an effort to bring European immigrants to five agriculturally based colonies in Pender and New Hanover counties, one of which was situated at Castle Hayne. MacRae described that colony, populated primarily with Hollanders, to his New York audience as having “six hundred people making a living, by intensive farming, on a tract of land which has a total of fifty acres.” Morton’s aerial image probably falls just outside the date range of the exhibit, the view provides a unique perspective of the area.

I’ve made two trips to the region photographing a few remaining traces of the colonies that, in addition to Castle Hayne, include St. Helena, Marathon (near Castle Hayne) and Van Eeden along U.S. Route 117, and New Berlin (later renamed Delco), and Artesia on U.S. Route 74/76. Elizabeth’s spring sojourn along U.S. Route 17 also touches on the Castle Hayne story, if you’re so inclined to wander off in that direction. I’m making one more trip to that neck of the woods tomorrow for more research, with camera in hand.

Justice's prayer

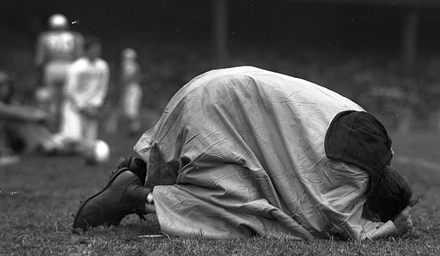

On an overcast November day in Yankee Stadium in 1949, UNC’s injured and idled All-American running back huddled to the ground and pulled his rain cape over his body. Hugh Morton pulled out his camera and trained it on Justice—Charlie “Choo-Choo” Justice—praying undercover for the Tar Heels, who were leading Notre Dame 6-0. It may be Morton’s most widely published photograph from that notable contest, whose final outcome was a 42-6 defeat for Carolina.

As I mentioned in my post on Friday, I just could not dampen the festive atmosphere for Saturday’s game by posting this photograph. Justice’s prayer was shattered in New York, but the Tar Heel victory this past weekend in Chapel Hill was “just deserts.”

Today I found a few more negatives from the 1949 game and I have scanned several of those found thus far. I hope to put up a selection in the next day or two.

The Tar Heels against the Fighting Irish in the Big Apple

Tomorrow afternoon, Kenan Memorial Stadium on campus will be in the hub of excitement that accompanies UNC football, magnified by the mystique of its opponent, Notre Dame University. Earlier this week I wrote a blog post for our sister blog, North Carolina Miscellany, featuring photographs in the Photographic Archives made by Bob Brooks in 1949 when UNC first played Notre Dame. That game took place in New York City’s Yankee Stadium. And if you didn’t already know or deduce . . . Hugh Morton was there.

I cannot bring myself to include in this entry Morton’s most memorable photograph from that contest. It’s just too heartbreaking to post amidst the anticipation and excitement of tomorrow’s game. I promise to publish it on Monday. Instead, here’s a festive pre-game photograph made of UNC’s mascot Rameses and fans in the lobby of a New York hotel:

As usual, we’d love to hear from you with identifications if you can.

I spent a good portion of today tracking down negatives from the game (I’ve found some) and trying to confirm that a group of them are from Yankee Stadium. The day escaped from me in the process, so I’ll post the game photographs on Monday.

Serving up server space

Elizabeth’s last “Behind the Scenes” post on our file nomenclature has a flip side: “Once you name them, how do you organize those scans on the server side?”

Two weeks ago I received what I’ve kiddingly called a “cease and desist” order from our IT department. At seven minutes before closing, I learned that our “projects” drive—where we’d been storing our scans from the Morton collection (among other collections)—was full. I knew this and had already started working on the problem earlier in the day. The friendly caller from the Library IT department was nicely adamant, however, in his insistence that before I left the office that evening I had to remove at least 10 gigabytes of data, and continue the process the next day. The Morton scans had already amounted to 140 gigabytes; respectable, but not immense . . . unless you do not have the room!

The Library’s long-term storage configuration, the Digital Archive, has lots of disk space, but that server is designed for little to no alteration of files, file names, or directory structures once files get deposited there. That’s with good reason: you don’t want to be accidentally renaming, deleting, or copying over files intended for long-term storage. Our short-term storage is the projects drive, a server meant to be used as an interim holding tank for scanning projects before transferring files to the Digital Archive.

Scanning as a processing tool represents the antithesis of the long-term storage model; “in process” scans are not necessarily ready for prime time because we don’t know what many of the images depict. By scanning negatives, for example, we get to see the images to aid in identification. We also have the possibility of matching up related negatives or slides that have been separated as their relationships are rediscovered. The resultant scans, however, can set on the server for a long time before any file name or directory manipulation might take place, and that runs contrary to the purpose of the project drive.

So scanning during processing fits neither storage model. Well, where (and how) are we going to put 140 GB of data? That’s not a huge amount on the face of it, but it is only going to keep growing, so we needed a file structure that would handle that growth, and one that the IT department could accommodate on the systems side, too.

Here’s what emerged:

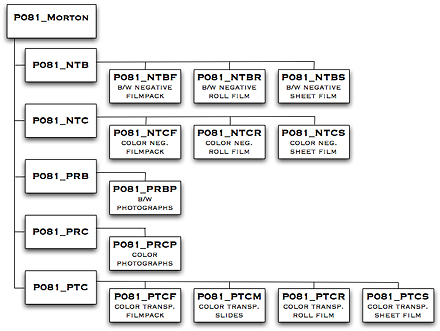

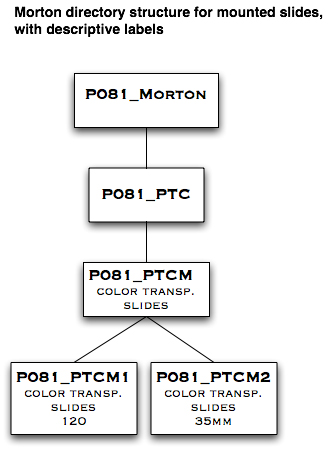

The diagram above shows the directory structure for the Morton scans. The top-level directory is P081_Morton, with five (for now) subdirectories: NTB (black-and-white negatives), NTC (color negatives), PRB (black-and-white photographs) , PRC (color photographs), and PTC (color transparencies, which are positives). Each subdirectory has a number of subdirectories that further refine the category, as do those subdirectories have additional subdirectories. The following diagram illustrates the file structure for color transparencies, showing the mounted slides at the base level:

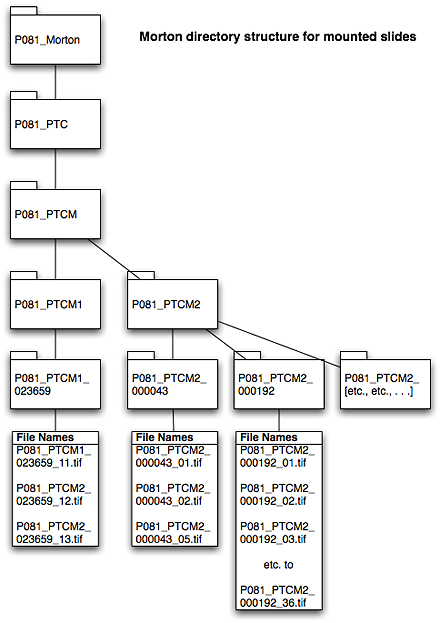

An illustration showing individual scans for 35mm slides, then, looks like this:

On the server side, we have re-conceptualized the notion of the Digital Archive. In the long run, we may end up with a third type of storage for longer term projects with sizable and flexible storage requirements that allow us to rename files, move them around into different directories, et cetera, and then formalize them before they are moved into more permanent storage. Until then, IT is unlocking the restrictions placed on the Digital Archive to accommodate our immediate needs. (And we are not the only ones scanning lots of material!) In the final scenario, the university’s Institutional Repository will be the ultimate long-term preservation storage solution, but that is a few years in the offing. For now, we’ll be using the approach above . . . and keep on scanning!