When is a Volunteer a Tar Heel? When he’s Jack Hilliard, our devoted volunteer (with an upper case “vee” in this case for Valiant, of course!) with the Hugh Morton Collection. Jack has contributed several posts on A View to Hugh, and his latest covers the history of football contests between teams sported by the University of Tennessee Volunteers and the University of North Carolina Tar Heels. After Tennessee paid a hefty $750,000 fee last year to cancel the schools’ confrontations for the 2011 and 2012 seasons, irony brings the two one-time rivals together this year to face each other on December 30 in the Franklin American Mortgage Music City Bowl.

The Volunteers from Tennessee and the Tar Heels from North Carolina fought side-by-side during the American Civil War. Twenty-eight years after those hostilities ended, however, the University of Tennessee Volunteers and the University of North Carolina Tar Heels took up a different battle—on opposite sides of a gridiron.

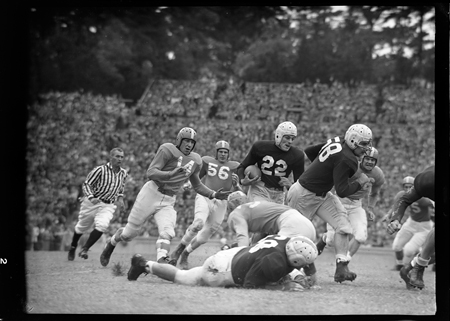

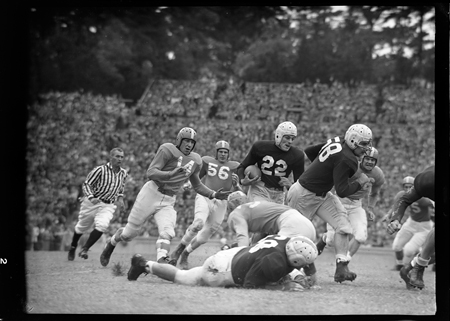

That first battle took place on an old athletic field south and east of Smith Hall on the UNC campus. It was November 3rd, 1893 and the Tar Heels won that day 60 to 0. The teams would not meet again until 1897—this time in a driving rainstorm on Curry Field in Knoxville, and once again the boys in blue were victorious. The next game, in 1900, was also a Carolina win, but finally the Volunteers beat the Tar Heels in 1908 before 2,000 fans in Knoxville. Between 1909 and 1918, there were no games; the 1919 game, according to author Smith Barrier in his 1937 book On Carolina’s Gridiron, being played in “two inches of mud” and ending in a 0-0 tie. When the Tar Heels went to Tennessee in 1926 the game was played for the first time on Shields-Watkins Field, where UNC lost again by a 34-0 score. The Heels suffered another loss in ’27 when the series finally returned to Chapel Hill where 7,000 turned out for the game on Emerson Field. The photograph above (not by Morton, but from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Image Collection, 1799-1999) depicts Tennessee’s “Breezy” Wynn getting tackled during the 1931 contest—a 7-to-0 Tennessee victory—held at Chapel Hill during Kenan Stadium’s fourth year. Carolina wouldn’t win again until 1935, and then again in 1936. Eight seasons would come and go before the teams would meet again. Starting in 1945 and continuing until 1961 the teams met every year alternating home and away.

The 1946 game is considered by many to be a classic. Head Coach Carl Snavely took his Tar Heels to Knoxville to meet Head Coach General Robert (Bob) Neyland’s Volunteers on November 2nd. Carolina was ranked #9 and Tennessee #10. About 1,500 students and alumni made the trip over the mountains, many on a special train called the “Football Caravan” which pulled out of Durham on Friday, November 1st with 10 sleeper cars. Two of those cars carried Director Earl Slocum and the Carolina Band, which was making its first trip since the Second World War. The Volunteers took an early 6-0 lead, but early in the second quarter the Tar Heels pulled off a play that is still talked about when UNC alumni and friends get together. With the ball at the Carolina 27-yard-line, UNC’s Charlie Justice dropped into deep punt formation. He faked the punt and took off around his left end, he then reversed his field two times and finally scored. In the record book, the played covered 73 yards, but all who saw the play believe Justice covered more than 100 yards. Many of those fans call it Justice’s greatest run—including Charlie himself. Justice teammate Joe Wright related the story of the famous play at the Justice statue dedication in 2004. Wright said that all 11 Tennessee players had a hand on Justice at some point and that tackle Dick Huffman (known as “Big Sid)” had “two shots at him.”

Snavely called it one of the outstanding plays he had ever seen; Vols Coach Neyland agreed. Duke Assistant Coach Dumpy Hagler who was at the game scouting the Tar Heels said it was the greatest he had witnessed in many years watching football. And teammate Jack Fitch told Justice, “it was the prettiest thing I ever saw.” Replied Charlie, “Thanks Jack, but it wasn’t good enough to win.” Tennessee won that afternoon 20-14, much to the delight of the 35,000 in attendance.

The following year it was Tennessee that made the trip over the Smokies and came into Chapel Hill on November 1st, 1947. The Tar Heels, led by Justice, put on a 20-6 winning performance before 40,000 fans that Saturday afternoon. UT’s yearbook “The Volunteer,” described the game this way:

“Choo Choo Justice and his traincrew, all steamed up because of last year’s loss to Tennessee, engineered a victory over the Orangeclads.”

It was during this game that Hugh Morton took the photograph above, his most famous image of Charlie Justice. In fact, it is one of the most reproduced pictures in the entire Morton Collection. The picture is featured in Morton’s 1988 book, “Making A Difference in North Carolina” . . . it’s on the facade in the east end of Kenan Stadium . . . it has been printed in the UNC Football Media Guide many times (twice on the cover) . . . it was printed on the cover of a Justice Celebrity Roast in 1984 . . . was on the game-day ticket for the game with Tulsa in 2000 . . . and the Justice family selected it for the front of the bulletin at Charlie’s memorial service in October, 2003.

On October 30th, 1948, the largest crowd in Tennessee sports history to date, witnessed another Tar Heel victory. Before 52,000 fans the number three ranked Tar Heels beat the Vols 14-7. Justice passed to Bill Flamisch and Art Weiner for Carolina’s touchdowns.

Early in the 1949 season Carolina lost a game at LSU, but when the team returned to Chapel Hill about 5 PM on Sunday, October 23rd, hundreds of students were gathered on the steps of Wollen Gym and hundreds more lined the street and surrounding area. Several emotional speeches were given by the players and Head Cheerleader Norman Sper closed the ceremonies by leading a mighty cheer . . . “BEAT TENNESSEE” . . . Carolina’s next opponent. But that didn’t happen. The Vols were victorious by a 35-6 score as 44,000 dazed fans set in Kenan under threatening skies. This game would become a significant entry in the record book. Tennessee became the only team to beat a Justice Era UNC team twice.

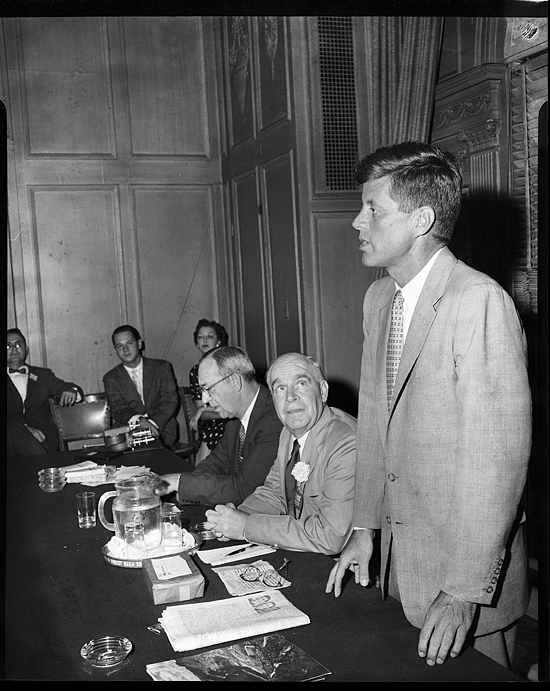

Tennessee continued its winning ways over the Tar Heels during the next eight years while winning a national championship in 1951. When the Volunteers came into Chapel Hill in 1953, the “Gridiron General” Robert Neyland had stepped down as head coach and stepped into the athletic director’s job. Photographer Morton captured Neyland in his new role. Morton also deftly captured a Tennessee cheerleader with her skirt whirling about her.

The Tar Heels would finally win again in 1958. UNC’s “Alumni Review” headline: “Tar Heels Top Tennessee Jinx and Win 21 to 7.” The Volunteers would pick up two more wins in ’59 and ’60. The most recent Tennessee–Carolina game was played on November 4th, 1961 and like that very first game in 1893, the Tar Heels won; the score in ’61 was 22 to 21. Although Carolina has won only 10 games in the series while Tennessee has won 20, Carolina will take a one-game winning streak against the Vols into the Franklin American Mortgage Music City Bowl on Thursday, December 30th, in Nashville—a game already in the record book because it will be the first meeting between the two teams in a bowl game.

Copyright Don Sturkey, 1959. North Carolina Collection.

Copyright Don Sturkey, 1959. North Carolina Collection.