13 November 1937 marks the creation of Sadie Hawkins Day by Al Capp in his cartoon strip Li’l Abner. The notion of girls chasing guys one day a year lept quickly from newspaper page to high schools and college campuses across the country. Two years later, Life magazine covered the phenomenon in a photo essay entitled, “On Sadie Hawkins Day, Girls Chase Boys in 201 Colleges,” featuring photographs made at Texas Wesleyan University by Fort Worth Press photographer Wilburn Davis.

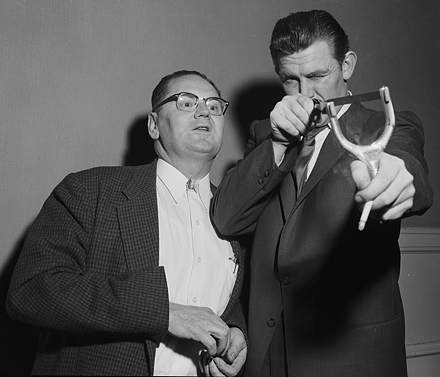

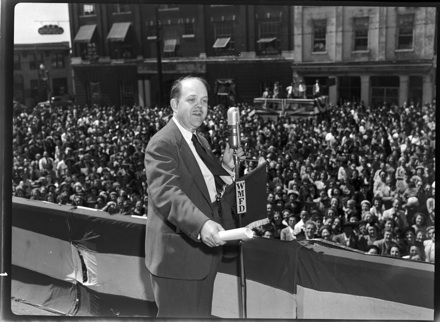

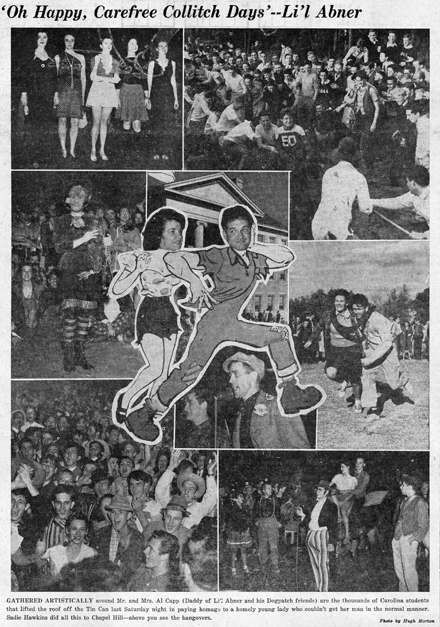

On Saturday, 8 November 1941, the UNC student body reveled in all-day Sadie Hawkins Day events. Al Capp and his wife came to Chapel Hill to participate in the festivities . . . and so, too, did a photographer from LIFE magazine. No surprise then that UNC student photographer Hugh Morton was also there with his camera. Thus far two Morton negatives from the day’s event have surfaced, and both are viewable online in the Morton digital collection. One of those images is the full view used for the cut-out inset of the Capps with their faces poking out from headless cartoon characters in the photomontage seen above.

The photomontage appeared on the front page of The Daily Tar Heel for 11 November along with stories of the event. The trademark “Photo by Hugh Morton” byline can be seen in the lower right corner, but since it doesn’t say “photos” in the plural it’s not clear if the others are also his photographs or if the credit referred to the entire montage. (The Capps portrait and other photographs of the day’s activities also appeared in The Alumni Review.) The photographs show some of the goings-on for the day, mostly at Emerson Field, that included an “earth shaking tug of war, and Dogpatch games.” A “Gingham Gallop,” which was a “girl-break tea dance,” with coeds having to wear gingham, cotton, or plaid and a hair ribbon capped off the celebration at Graham Memorial.

LIFE published its photographic story, “On Sadie Hawkins Day, North Carolina Co-eds Show How to Kiss Girl-shy Boys,” in its 24 November issue. On 15 November The Daily Tar Heel editors took the photographs in the 24 November issue of LIFE to task in a brief commentary entitled, LIFE Misses The Boat.” (Yes, those dates are correct!) The story and photographs, they complained, were a “hill-billy layout.”

Campus opinion has it that the article misrepresented not only the festive day itself but the University. It appeared that LIFE was seeking leg-art, used only posed pictures, none of the actual extemporaneous proceedings.

LIFE’s photographer, as a matter of fact, did not even appear at the tug of war games which developed into a good-sized mud-battle, nor at the big dance. If the magazine wanted sex, it didn’t have to travel this far south.

In fact, it quite seems that LIFE missed the boat. The article lacked the verve and spice of the event—and terming Carolina men “girl-shy” is a prodigious masterpiece of understatement.

With such criticism, with which I agree, the surprise in this story is the photographer LIFE sent for the occasion: none other then venerable W. Eugene Smith.