I initially wanted to write a post for the 50th anniversary of John F. Kennedy’s campaign swing through North Carolina on 17 September 1960. The story behind Kennedy’s trip to the Tar Heel State fascinated me, however, so I launched into Triumph of Good Will, John Drescher’s account of the gubernatorial contest between Terry Sanford and I. Beverly Lake that preceded Kennedy’s visit. There’s an interesting story that photographs by Hugh Morton and other photographers in the North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, can help tell. In light of the silver anniversary of that momentous campaign, and during the anniversary month of Kennedy’s assassination, I’ll be contributing a series of posts touching on that pivotal time in North Carolina and the nation.

September 17th, 1960—just nine days before this country’s first televised presidential debate—found Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy campaigning in the Tar Heel State. Two months earlier, Kennedy had emerged victorious as the party’s nominee at the Democratic National Convention, held July 11th through 15th at the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena. The pivotal connection between these two events was North Carolina governor-elect Terry Sanford. The Kennedy–Sanford alliance crystallized during the Democratic National Convention, but first some back-story.

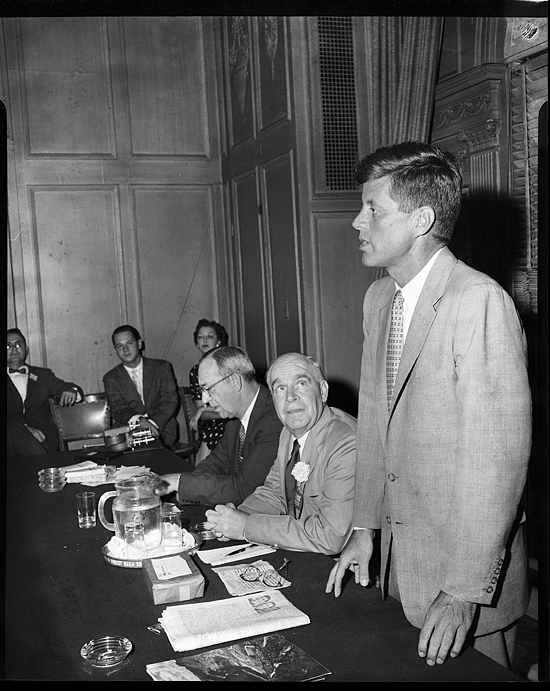

According to Drescher, the first time Terry Sanford spoke to John Kennedy was in early 1959, when the Charlotte Chamber of Commerce invited Kennedy to address its members. Kennedy agreed and, in return, asked the Chamber to invite delegates who attended the 1956 Democratic National Convention (DNC). Sanford had attended the DNC, but supported Estes Kefauver. Kennedy and Kefauver emerged as the two top candidates for veep after presidential nominee Adlai Stevenson decided that convention delegates would choose his running mate. Delegates select Kefauver by a final margin of 755.5 to 589, with the third place finisher Al Gore, Sr. receiving 13.5 delegates. North Carolina Governor Luther Hodges received 40 votes on the first ballot, but none after the final tally. Morton photographed Kennedy speaking to the North Carolina caucus as a candidate for vice president at the 1956 DNC, as Luther Hodges, seated to Kennedy’s right, watched and listened.